Interview highlights

This is an edit of the ‘interviews by topic‘. That one splices together the entire interviews, this one takes parts of those to create a more concise overview for those looking for a starting point and unwilling to read the epic full version.

This is an edit of the ‘interviews by topic‘. That one splices together the entire interviews, this one takes parts of those to create a more concise overview for those looking for a starting point and unwilling to read the epic full version.

Jill Bryson interviewed 9 June 2001

Rose McDowall interviewed 29 Jan 2002

David Motion (producer) interviewed 2 Aug 2002

Robin Millar (producer) interviewed 16 Feb 2003

Bill Drummond (manager / A&R) interviewed 26 April 2003

David Balfe (manager) interviewed 19 May 2003

Tim Pope (video director) interviewed 22 June 2006

John Cook (bassist) interviewed 6 November 2024

Most of these interviews were conducted a very long time ago – bear in mind that those involved may express opinions they no longer hold.

Backgrounds and forming the band

Polka dot picnic, Kelvinbridge, Glasgow, 1982. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

Q: Generally, how does it feel looking back at Strawberry Switchblade?

Rose: Brilliant. I think it was a totally fantastic exciting period of my life.

Jill: It was a good thing to do. It wasn’t planned and it wasn’t expected, but it was a good thing to do. It was fun.

Rose: Once things started to snowball it went really really quickly, which was also the demise of Strawberry Switchblade, because the more that’s going on the less control you have over what you’re doing, and the more other people are making decisions for you.

Jill: Being with a major label and being female, they push you down one particular road. I don’t think they quite understood where we were coming from. They want to push you to be glamorous and they want you to be poppy and sell your stuff. I don’t mind pop music, I wanted it to be poppy, and it was the 1980s. I’m pleased with it. I think it was more the publicity machine behind the big record company that pushed us, there was a lot of fighting against that.

Rose: Inevitably it ends up being not what you started out for it to be, so I didn’t think it was worth continuing because it wasn’t fun any more. It was arguing with the record company about everything, and I thought ‘this was not what I wanted’.

Q: What started you in music? What music did you grow up with?

Rose: I had three sisters and they all liked different kinds of 1960s music so I got to hear quite a wide range of stuff and picked out the things I liked the best, which tended to have lots of harmonies which were a bit psychedelic or the Velvet Underground – Lou Reed was just a total genius songwriter. He is god!

Q: When did you start writing yourself?

Rose: There was a big concert in Glasgow at the Apollo Theatre, which doesn’t exist any more, I think it was a Stiff tour or something. There was loads of different bands, and the Ramones were playing. I was there with my boyfriend at the time and we just looked at each other an thought ‘if they can do it we can do it!’.

Q: Is that what led to forming The Poems, your band before Strawberry Switchblade?

Rose: Yeah. Strawberry Switchblade and The Poems did gigs together, cos I used to organise a lot of the gigs in those days. That was good fun, but then The Poems fell apart basically cos Switchblade got busy.

Q: You came out of art school didn’t you?

Jill: Yeah. I did a lot of photography and film, painting.

Q: How did you and Rose meet?

1977, teenage punks at Glasgow Queen Street station. Rose, Drew McDowall, Jill and Margaret Broni at the front. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

Jill: I met her through the punk scene in Glasgow which was tiny at the time, around 1977. There were so few, you knew everybody who was a punk. It was the first thing I’d ever been involved with, I was sixteen. But I didn’t know Rose well, I just saw her around and knew her, she was quite a character.

Rose: Jill and I were really good friends, and we were pretty notorious around Glasgow for going around all dressed up. Not really so much in the early days, but when I was in The Poems I used to be overdressed, outrageously dressed all the time. It was a really big deal being a punk then.

When punk happened it totally saved my life. I was a really fucked up teenager who really did not want to conform to the norm, never had even when I was a kid. I didn’t want to be like everybody else because I didn’t respect them. But I was at that age where I felt ‘what am I supposed to do?’, and then punk happened. ‘That’s what I’m supposed to do! I’m supposed to be me!’

Punk allowed me to be me without feeling like a fake. It totally liberated me. I didn’t have to be a girly girl and it wasn’t expected of me, or if it was it didn’t matter. I would probably have done the same thing anyway but been really outcast or locked up for being a nut. My mum was always telling me I was a bit crazy. Punk really was my saviour.

Jill: All the punks in Glasgow used to go to the cake shop Rose worked in and she used to give them out free pies and things. Her and her friend Linda worked there and they were sacked for having blue hair. Nobody had blue hair then, nobody. They took them to a tribunal and got their jobs back!

By the time I knew Rose she’d stopped working there, and then having a baby and being stuck out in Paisley and being married, she was out of circulation for ages cos she had a baby to look after. Then she started to come out again and by that time I was living up in the West End and I was at art school. Her child was quite young when we started, only about a year or two old.

Q: That’s a phenomenal amount of drive isn’t it?

Jill: Absolutely. She did not lack drive.

Q: With that sort of background, if you feel insecure from it, and then having a kid and everything when you’re still in your teens and finding yourself, and then you’re responsible for the kid as well; to get out there and do a band on top of all that is utterly phenomenal.

Jill: Absolutely. Also with the lack of education, yet she was writing lyrics and doing well. I wish I’d been a bit more understanding at that time. But by the time we’d moved to London and it got huge I just wanted to punch her! It just went to her head and she just wasn’t equipped to deal with it. She wasn’t equipped to deal with success, and it was very difficult to handle.

I spent most of the time in tears once we were signed and had to do stuff. It was no fun, I didn’t want to do it any more. I was ‘what’s the point? I don’t care whether I’m on TV, I don’t care about that crap’. I wanted to do it because I liked her and I liked writing with her and it was funny and we had a laugh, we had a really good laugh.

And yet we still managed to do stuff that meant something to us and that we enjoyed doing. There were some great times, some really good times.

Q: Was it the punk thing that made you start playing guitar?

Jill: Yeah. Before that I would’ve thought you’d really have had to play it, be able to play solos and rock guitar and, shit, I’m not going to do that am I? Women didn’t really form bands did they?

At that time I really liked Patti Smith, I’d got Horses when it came out. It was just amazing. I wanted to be her, I wanted to look like her. I knew there was no way I could ever look, you know, wasted. I was always going to look, well, healthy.

I thought Patti Smith was fantastic but she looked like a boy and her band were men. But then when punk started there was X-Ray Spex and Siouxsie, and The Adverts had a girl bass player, just loads and loads of women started appearing in bands like The Slits. I thought it was great. It was about enthusiasm and not about ability, it was about ideas.

And also I thought, well, if I just hammer something out and have the confidence to get up and scream into a microphone I could do it. At the time I was a bit too young, I didn’t have a guitar or anything, didn’t know anybody else who was in a band.

After that there were two or three punk bands in Glasgow and I remember singing with some of them in rehearsals and stuff.

Q: So when did Strawberry Switchblade get formed?

Jill: ‘That’s me with Edwyn Collins from Orange Juice and Alan Horne of Postcard Records. That’s early, that’s probably 1981, before the band. That’s outside Postcard Records, I lived round the corner.’ Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

Rose: I was sitting on a bus with James Kirk from Orange Juice. He was coming out to my house and he’d done this fanzine called Strawberry Switchblade. He said he wasn’t going to continue doing the fanzine, I said that’s a fantastic name, it can’t just die, and he said ‘have it’. I had the name Strawberry Switchblade so I had to form a band cos it was such a good name!

Jill: I was at art school when we started to do it. I had a flat round the corner from Alan Horne, the guy who ran Postcard Records in Glasgow. They were just a real strange bunch of people who shared a flat. It was such a weird, strange, great place to go. And then Edwyn who was the singer in Orange Juice lived round the corner, and David McClymont the bass player lived up the road.

Knowing Orange Juice and that lot, they were just like, ‘oh yeah, you should be in a band, you should do this, you can do demos with us’. It was actually the guitarist in Orange Juice that came up with the name Strawberry Switchblade. I think it was going to be the name of a fanzine or something, which he’d got from a psychedelic band called the Strawberry Alarm Clock, and it was just his punk version.

Q: Did you play any instruments in any bands prior to Strawberry Switchblade?

Jill: No, just did some shouting into the microphone and that was about it.

Q: So you decided to start a band and then started writing songs? There’s so much in this story that’s the other way around from normal – having a Peel session without sending in a demo, having sessions booked without having the songs, having a name but no band.

Rose: I know! So I bought myself a 12 string guitar and taught myself to play a few chords – which is all you need to do to write a song – and Jill bought a guitar.

Q: Had you been playing guitar before that?

Jill: No! My sister had a classical acoustic guitar that she knew a few chords with, and she had a ‘learn to play guitar’ book, Burt Weedon or something like that. A classical guitar’s got such a wide neck and I thought, ‘never!’, the action was so high you were like [straining face] even to play G. So I learned a few chords – literally about three – and thought, well we can do it, I know three chords.

Q: Who were the other two?

First ever Strawberry Switchblade gig, Spaghetti Factory, Glasgow, December 1981. Carole McGowan (drums), Janice Goodlett (bass), Rose McDowall (vocals), Jill Bryson (guitar). Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

Rose: The other two were Janice [Goodlett] who played the bass and Carole [McGowan] who was a drummer, her brother taught her to play drums. She had two rhythms she could play, one was for the slow songs and one was for the fast songs. Which was OK, cos if you’ve only got eight songs it means you don’t have time to get bored!

Q: How quickly did it develop?

Jill: Really quickly. We got together, wrote a couple of songs then booked a gig!

Q: Did you think at the start you were going to make a go of it as a really serious thing?

Rose: We just thought ‘let’s join a band and have fun’, cos Orange Juice were our friends, all our friends were in bands, I was in The Poems at the time and it was just really easy. Punk made it really easy to be in a band as well. When I was a kid growing up that’s what I always wanted to do.

I remember in school when the careers officer came round and was asking everyone what they wanted to do, and they were saying they wanted to be a nurse or work in a steel factory or a shipyard, and I said I wanted to be a brain surgeon or a pop star, and everybody in the class just started laughing. I remember when we were first on Top Of The Pops thinking ‘I wonder if any of them are watching now?’

Q: How long did Strawberry Switchblade last as a four-piece?

Rose: God, not very long at all. Until Strawberry Switchblade started getting really busy actually.

Jill: We didn’t actually play that many gigs with them. I think we must have been together about six months, nine months maybe. I can’t actually remember what happened.

Rose: We became a two-piece when we started doing the Peel sessions [it was a little earlier – NME dated 7 August 1982 said iti had already happened]. I was still going to do Poems things but it was getting a bit silly cos I was practising all the time with Strawberry Switchblade. And also I had a daughter so Drew, my partner at the time, he would be babysitting while I was doing Strawberry Switchblade things.

Q: Were the band any good at this time?

Jill: I don’t know. People liked us, but I think it’s just because we were women and we did little short pop songs. It was the same songs, Since Yesterday and stuff.

Q: So the very first stuff you were writing was the stuff that ended up on the album?

Jill: Yes. Most of them. They went through change as we progressed and learned an extra chord. The lyrics got a bit more refined. Some of them changed even at the stage when we were doing the album, and we had a producer saying ‘work on that bit there’. But to begin with it was still those songs.

Q: You’ve just picked up a guitar and you’ve just started to write songs and it’s those songs!

Jill: It was literally, ‘we’ve got to write some songs! How many have we got now?’. We started doing a few little gigs around Glasgow which kind of pushed us each time cos we’d have to rehearse for them. I remember sitting at home, at my parents, sitting in the back room till god knows what time just strumming, trying to come up with something.

Q: Who did what in the songwriting?

Jill: When we started off I used to just do the melodies and write the music and she did the lyrics. I wrote Trees and Flowers on my own. Sometimes if I was playing I’d come up with something [lyric-wise] to fill it in, to help with the melody and the flow, and we’d just stick with it.

And as we went on Rose decided she would learn to play guitar as well – if I could do it in three months she could! Then she started to write her own music as well.

Q: So did it get more collaborative or did it make you develop ideas separately?

Jill: It did get more that one of us would come in with a finished thing. To begin with I came in with the tune and the melody and she’d tape it and go off and write the lyrics, but as soon as she learned to play a few chords she did her own stuff. But then we’d kind of get together to rehearse it, thrash it out a bit.

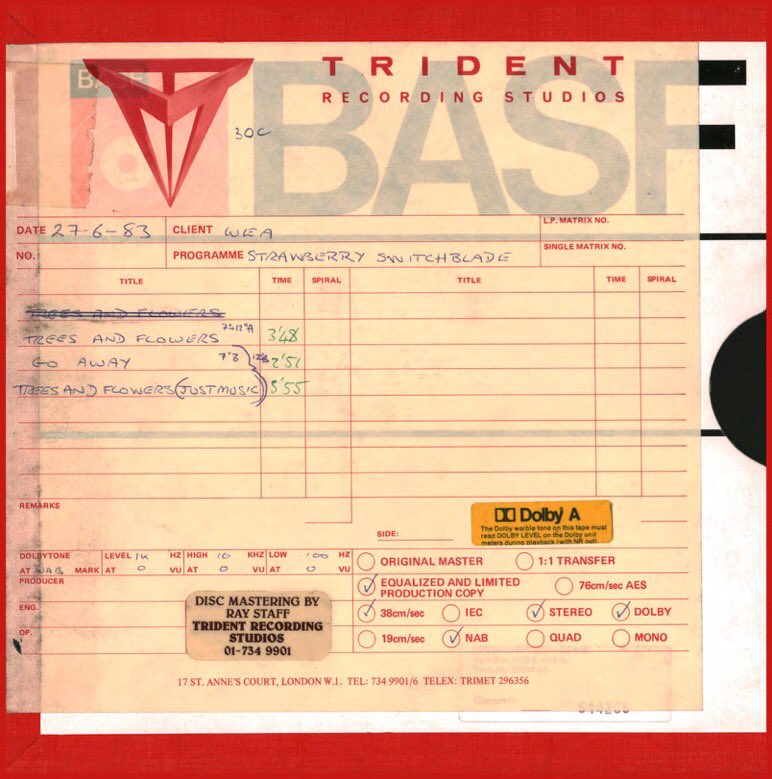

First recordings, BBC sessions and Trees and Flowers

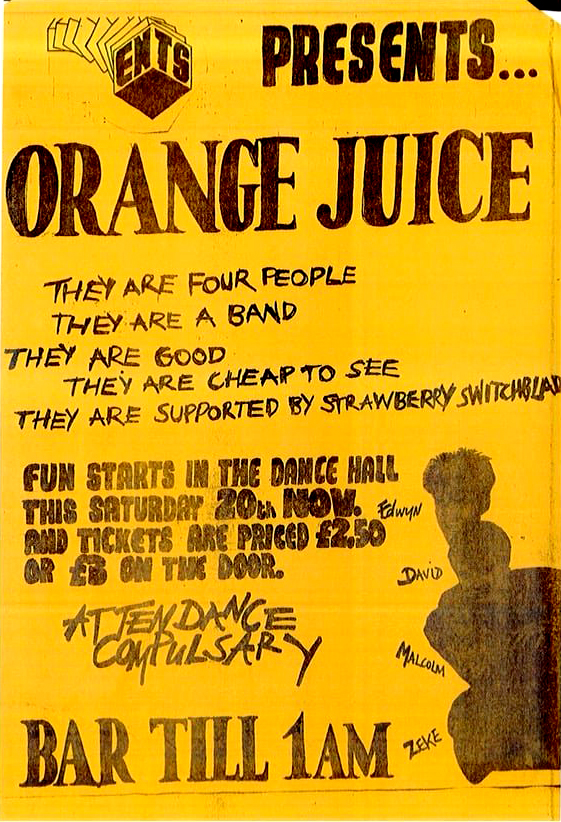

Poster for Strawberry Switchblade supporting Orange Juice at the University of Essex, Colchester, 20 November 1982

Q: You’d gigged as a four-piece, but with the other two leaving did it put gigs out of the way?

Rose: We started using backing tapes. It was before the records came out, we had a reel to reel with basic bass and drums on it.

Q: So how did you get signed?

Jill: You know, it was just weird, the whole thing was so weird. We’d been playing a few gigs in Glasgow and people obviously thought of it as a weirdo band of its time and place. I think Orange Juice had been signed by that time and it was Jim Kerr. Because he was one of the first Glasgow punks he remembers Rose particularly. And I don’t really like Simple Minds, but they were being interviewed, I think it was on [Radio 1 show with DJ] Kid Jensen, and he asked them what’s happening in Glasgow, what other bands are good. And he said ‘Strawberry Switchblade, they’re good’, so Kid Jensen’s producer got in touch with us.

Rose: We did the John Peel session and then we did the Kid Jensen session. We recorded the Peel one first but Jensen went out first.

[BBC archives say the Peel session was recorded on 4 October 1982 and broadcast on 5 October, Jensen was recorded on 3 October 1982 and broadcast on 7 October]

Jill: We had to pick four songs, and there was only the two of us so we had to get a band together. James Kirk from Orange Juice played bass and we had a guy called Shaheed Sarwar, who we all called Shaheed StarWars, played drums. He was in a band in Glasgow, I can’t remember what they were called. Basically it was the four of us and we had to rehearse. And we were all ‘it’s OK, it’s only four songs, we can do it we can do it’.

Q: Did you submit demos or anything?

Rose: No, we didn’t! No, he just phoned my house – not even getting the producer of the show to phone – and said ‘Hi, this is John Peel, do you want to do a session?’ I said ‘do you want us to send a tape?’ and he said, ‘no, that’s OK’. Then David Jensen did it as well just cos John Peel had, they were both trying to be the first one to get us out.

Q: He hadn’t heard you at all?

Jill: No!

Q: Isn’t that weird?

David Balfe meets Jill Bryson and Rose McDowall for the first time. The Garage, Sauchiehall Street, Glasgow 1982. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

Jill: Yeah, really weird.

Q: Do you know how many tapes Peel got, and yet he hired you people who he’d never heard?!

Jill: At that point it was the Peel session you really wanted to get rather than a Jensen session, but we weren’t going to turn down either. So we ended up doing two sessions within about two weeks of each other. We had to have eight songs to do it and we only had six so we had to write another two!

The Jensen session was a bit more upbeat, the Peel session was a bit quieter. It was just weird, it was wild, absolutely wild. I remember the Jensen session was the first proper recording we did and the producer was Dale Griffin and another guy from Mott The Hoople and I could hardly sit next to them. I could remember them from when I was fourteen, I was hyperventilating, I could hardly play.

We did that and then Bill Drummond, who was Echo and The Bunnymen’s manager, phoned us and said he [and David Balfe] had heard the sessions.

Rose: They came up to Glasgow to meet us and propose that they two would be a management team for us. It ended up that Balfey was our manager solely cos Bill Drummond had to concentrate on running the Bunnymen and they didn’t want him to spread himself out too much.

Bill Drummond: Dave Balfe told me about that and maybe he’d got a tape of it, a tape that included Trees and Flowers [the Peel session, broadcast on 5 October 1982]. I remember as soon as I heard that song I thought it was fantastic. Absolutely genius song.

So the two of us went up to Glasgow to meet up with them.

David Balfe: It all went together, this soft and fluffy side with the dark and edgy side which I liked the combination of. I liked it artistically and I thought it would be commercial. I thought the name perfectly embodied those aspects, in that Jill was the strawberry and Rose was the switchblade.

They also had this image which was very distinctive and very focussed, which I thought would work well and it did work well, but it also had the problem in that very quickly people could see… I mean, it was the classic one-hit wonder in that they had a light and frothy gimmick image, got attention initially but then it didn’t look like it had any depth. And it didn’t really.

So that was it really. Although Bill and I had managed the Bunnymen and the Teardrops together, with the Teardrops ending I was kind of low in self-confidence at that point and it just seemed to be a thing I liked a lot and could get on and do.

Bill Drummond: On meeting them, the fact that they had got the whole fuckin’ look together, the whole package, in that sense added to it. Not just from a cynical commercial point of view, but they just knew what they were about, they were expressing themselves on a lot of different levels other than just writing lyrics and tunes. It was working in a lot of different ways and obviously it was working in a way that could reach out there.

And that look had a genuine artistic depth but also at the same time you knew it could work in a then-Smash Hits way as well. They were the genuine thing, they were real genuine artists.

Jill: At that time he was working for Warner Brothers publishing. David Balfe had been in Teardrop Explodes [also managed by Drummond] and he wanted to get into management. The Teardrop Explodes had just split up, I remember him playing their last album to us, the one that never got released.

Q: It got belatedly released in 1990 as Everyone Wants To Shag The Teardrop Explodes. It’s not very good.

Jill: I remember thinking that when I heard it at the time. He was obviously very proud of it, he’d had a lot to do with it. So, I remember them coming up to see us in somebody’s flat, I think it was Edwyn’s, and they talked to us and said they’d like to sign us to Warner Brothers Publishing, and they’d like to put out a single too. They put out Trees and Flowers on Ninety Two Happy Customers records. It was Will out of the Bunnymen’s label, I don’t know if anything else ever came out on it.

Q: Trees and Flowers has got incredible personnel on it; you’ve got the rhythm section of Madness, you’ve got Roddy Frame from Aztec Camera on guitar, you’ve got Nicky Holland who was arranging and performing with Fun Boy Three, and you’ve got Balfe and Drummond producing. It’s laden with major figures from the time, this little first indie single.

Rose: I know! It was good actually. It was lucky, we just happened to be in a scene that was just buzzing with life, so much talent.

Bill Drummond: I think the record that Dave and I produced, Trees and Flowers, – and I don’t often say this about records I’ve been involved in making – but I still think it’s a fantastic record. And I think we were able to capture that fragility on that first single. There’s a friend of ours who played cor anglais, Kate St John, and that really worked well. I’m really really genuinely a hundred percent proud of that record. Then the trouble started, I guess.

Jill: We did this tour with Orange Juice and half way through we signed the contract with Warners publishing, in Liverpool. Then the single was released. It was such a bizarre tour, we did it in a hired car, just the two of us and a reel to reel tape deck. Drew, Rose’s husband, set it up with programmed drums and bass on it, and the pair of us would play guitar and sing. It worked, although sometimes the tape would keep going when we’d finished and stuff.

Q: Did Trees and Flowers do well?

Jill: It did well as an indie single, yeah. Top ten in the indie charts, and the indie charts at the time did sell quite well. And it was the only single we had that had posters. I remember seeing flyposters round London, we got our picture taken in front of one of them!

Rose: Then we had a lot of record companies start to get interested, a lot of the independents like Cherry Red and Rough Trade, and then some majors got interested. I think we went with WEA because, well, One: the advance [laughs] Two: the fact that they had a little subsidiary label that was quite cool to be on, it wasn’t quite selling out to a major. It was good to put the first single out as an independent before we went to a major.

Q: Do you think it would’ve been different if you’d stayed on a truly independent label?

Picture from the photo session that yielded the Trees and Flowers cover picture, in Jill’s flat, 1983. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

Rose: It wouldn’t have gone quite so quickly, it wouldn’t have been as rapid as it was. We may possibly have lasted longer, not split up quite so soon.

Bill Drummond: Even though it has a dark underside, it’s now perceived as mainstream pop. If they had been on a Glasgow indie record label and evolved like Belle and Sebastian or something like that, to live in Glasgow without having to move to London and all those things then a cult following could really have built up around them and what they do, and that would have been far healthier. If their careers could have evolved, maybe not having a Since Yesterday top five record but they could have had a genuine evolution which didn’t happen.

Q: It seems strange you weren’t on Postcard Records, given that you were around all the Postcard bands. Did you plan anything with them?

Rose: We may have done had things not happened quickly, and we gone the other way. We did talk about stuff, but Postcard were really starting to wind up by the time we were really starting to do things, because Alan was losing interest.

I think they knew us all too well at Postcard, they knew we only had eight songs, nobody else did! [laughs] So at the time we weren’t really ready to be releasing things. Everything kind of snowballed and just went the other way. We were quite interested in Cherry Red and then we got talked out of that one for Warner Brothers.

Q: So the plan was always to move them on to a major label?

David Balfe: Yes, yes. Well we had no money.

Writing songs, recording with Robin Millar

Rose and Jill on stage at The Warehouse, Leeds, supporting Orange Juice, 1 December 1982. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

Q: How did you write the songs?

Rose: Working with Jill was great, it was really really good because our personalities together were perfect for writing songs. She’d do something that would really excite me and I’d do something that would really excite her. The enthusiasm that came off each other was completely electric, it was so exciting and so much fun. And all we ever did was laugh. We were just really happy and we worked together really really well. I haven’t ever worked with anybody like that since then.

I kind of miss that, I miss our working relationship. It was really good for most of the time, it’s just that there became stresses towards the end. It was actually really good fun when we were sitting down and one of us would come up with an idea. We were good for each other, I think.

We were good for each other’s confidence – we were learning guitar as we wrote the songs, ‘I’ve learnt this new chord’ ‘Oh that’s really nice, let’s see if we can fit it in with the other ones we know’. It was like everything drew out of the same pot. We worked well together, we worked really well together.

Q: Although it was really collaborative, you were writing the lyrics on your own. Did you ever do much explaining of what they were about? In a format like the three minute song there’s bound to be so much left unsaid, but yours tend to be really uncontextualised. It feels like being dropped into the middle of a situation, like a snapshot of a relationship where although there’s clearly history and consequences, the lyrics have just picked a moment and described the feeling and feelings of that moment.

Rose: A lot of the lyrics were just straight out of my life, basically. It was a memory and I’d just put it into words like a poem. Little parts of my life that were stuck in my head, I’d write songs about them. Things like Little River, the reason I wrote that song is because it was one of my favourite story books in school when I was a little girl.

Things like Go Away, my cousin had taken me out into the countryside and he used to play really nasty tricks on me. He’d tell me to sit on this wishing stone, close my eyes and count to ten and make a wish. I’d open my eyes and he’d be nowhere to be seen, and I would have no idea where I was. That stuck in my head, and that was what Go Away was about, basically.

Q: Before you told me who wrote which lyrics, I’d seen 10 James Orr Street as an agoraphobic song, but you say Rose wrote it. What’s it about then?

James Orr Street, Glasgow – junction with Alexandra Parade, looking towards the necropolis. Glasgow had red police call boxes, unlike the blue in the rest of the UK (and on Dr Who)

Jill: 10 James Orr Street is where she lived when she was a child and she really loved it there. It was a council flat so the council could turf you out whenever they wanted. I think they were going to renovate them or knock them down. She didn’t want to leave, she loved it. Basically that was it, that’s what it’s about. I wrote the music for that one and just ‘la la la’d the thing to her and she wrote the lyrics.

She has much more of a gift for writing lyrics than I do. It’s not something I like to do, it’s not something I’m particularly good at. She’s got the gift so I was happy to go ‘this is the chords and the tune’ and she’d go and write the lyrics. They were good when they were simple like that [on 10 James Orr Street]. That’s the good thing about being part of a partnership, we both had different talents. I was completely happy with that song.

Rose: 10 James Orr Street, it was really my favourite place that I’ve ever lived and I really didn’t want to leave it. But they were knocking the buildings down to extend the hospital and we had to go. I was really heartbroken when I left that house cos my first love lived there as well, this little ten year old boy who used to run away from me all the time. I was giving him sweets and he was going ‘go away’. I was ten and he was nine. I just loved that place. So 10 James Orr Street was about having to leave somewhere you just really don’t want to.

The place I moved to afterwards turned out to be an absolute nightmare, an awful place. My little brother died within six months of us moving to that place. It was horrible because it was in sort of a gangland part of Glasgow, so it was really violent.

When I moved there I was ten years old, or just turned eleven I think, and I was totally, like, the world is a wonderful place. I used to find all these places that I’d call fairyland, I was just an innocent little kid who thought everybody could be saved if they only knew. Even bad people, if you talked to them and stuff they’d be fine, if they just knew what you knew they’d be fine. Then my little brother died, that really changed my perspective on life.

It was a horrible place for somebody who…. It was a horrible place for anybody, but I was somebody who was really optimistic and believed in all the beautiful things in life. Also I turned away from religion at that age as well, cos when my little brother died I thought that was a really cruel thing for God to do.

Q: Had religion been a big thing for you up until then?

Rose: Oh yeah, we were brought up Catholics and we went to chapel all the time. Then when the thing happened with my little brother I thought no. How can you possibly love somebody you’re terrified of? How can you force children – out of fear – to believe in something? I just thought there’s no way. I don’t believe in God, I’m not going to love something that I’m scared of who tells me I’ll burn in Hell if I don’t love him.

Q: It’s extraordinary how you can have gone from such a happy optimistic child to a place that forces you to see the other end of the spectrum. Something that always draws me back to Strawberry Switchblade is that bittersweet thing, the way it is dark and melancholy yet very delicate and beautiful. Self-contained partly to keep the world out but also because there’s enough inside to sustain, looking outside and reaching inside.

Rose: My whole life’s been like that.

Q: It’s that mix that makes the greatest and most moving pop music, that sort of thing that soars and yet there’s an ache, a worldly-wise ache, underneath it. The greatest pop music hits that, emotions that you can’t quite name from simplistic lists. It’s interesting seeing your growing up as so directly and intensely feeding that mix, that emotional blend that characterises the music.

Rose: I guess it’s that kind of influence that still influences my lyrics now. They’re still like that. I’m a kind of happy-sad person. I’d like the world to be a nice place, but it’s not. So I chose to live somewhere where it’s really beautiful and it’s really isolated and you sort of create your own universe. You can ignore things. If I could completely drop out I would, but I can’t cos I’ve got kids that go to school. If I was on my own I could easily see myself being an old woman in the woods. A witch in the woods who’d do potions for everybody, that would do me!

Jill: After we’d done the album it was most of the songs we’d come up with – we weeded a few out and obviously we refined them a bit – but basically it was those songs. And once we got ‘oh it’s serious isn’t it? It’s like a job, we’ve got to do this’, it kind of took the edge off it.

Q: There’s an extra pressure and weight when you know you’ve got to do something and you know where it’s going to go.

Jill: Yeah, and it was awful, that’s not really what it was about, it had been a really instinctive spur of the moment thing and that’s why it worked. Cos it wasn’t high art or anything, it was pop music.

Q: Well yeah, it is ‘just pop music’ and you can just hear it on the radio as you go past and you don’t have to give it your full attention to get something from it, but the great thing about pop music is that you can go as deep as you want with the good stuff, it can communicate and move you on a level as deep as any other art form, especially when it’s the performer’s own work. You can’t do that with Hear’Say but you can do that with, say, T. Rex, and certainly with Strawberry Switchblade.

Jill: Yeah, yeah I know. It’s interesting to find out what people are about when they’re writing stuff. If they’re not writing stuff then it’s just a case of performing it and do you like the performance of it or not.

Q: Is there any stuff you wrote the lyrics for apart from Trees and Flowers?

Jill: Who Knows What Love Is?, which is totally terrible and was supposed to be kind of, er, ironic. But it didn’t really work out that way.

Q: But set it to music and it just floats, it’s gorgeous.

Jill: I did that one, and Being Cold and Trees and Flowers. I think that’s the only ones I wrote words for, because I’m not really a lyrics person.

Rose: Later on we started getting people in, when we were doing bigger gigs. After the records we found musicians who we went on tour with and it worked out quite well. And some of the later sessions we did are with those musicians. It was good. We worked with the Madness rhythm section.

Jill: I think Madness had split up or they weren’t working or something cos I remember rehearsing with the rhythm section of Madness but it kinda didn’t work, it didn’t sound right.

And so then we had this jazz guitarist, a really nice guy – Simon Booth – he went on to be in a band called Working Week. The drummer Roy Dodds went on to be in Fairground Attraction or something, and there was a bass player, really jazzy kind of players, kinda weird.

Q: I can sort of see it, cos it would be important with Strawberry Switchblade to have musicians who don’t rock.

Jill: That’s it, yeah, that was it.

Q: Not just because it’s important that your records don’t rock but whilst maybe you’d get away with a bit of a noisy guitarist, having a rocking bass player and drummer would kill the subtlety and delicacy. The jazzy thing, at least it’s not rocking, it’s about subtlety and warmth rather than bombast, I can understand why you’d have tried that.

John Cook: It was a good, fun gigging band. We went everywhere from Brighton to Scotland to playing at the ICA. I was like a glorified session musician. It was a bit more than that cos they were very nice, Rose and Jill. They’d made us feel very friendly and part of the band.

Jill: They were pretty good as well, they didn’t overpower. So we played a few gigs with them but it didn’t really work.

Q: Did you gig much?

Jill: No, not really.

Q: Recording the album, what was that like?

Jill: We did some recording with a band, produced by Robin Millar, a really nice guy, he had studios up in Willesden somewhere and we recorded with him and I enjoyed it. This was before the album, he was going to produce the album. But it ended up none of us were sure, us, the record company; it had come out quite mellow, and with the band it just didn’t work with the songs which were three chord wonders. It was missing the point.

There was one we did with Robin Millar, Secrets I think it was, he did a really nice version of it, did a fantastic vocal thing layering up vocals, really ethereal, really beautiful and choral sounding. Just lovely.

Robin Millar: And that is partly to do with this very kind of churchy thing which Rose sort of gave off, this very black candle holiness sort of thing, and I loved their two voices together. I thought well, if you hear them together at some point in the song then you’ve found the centre of what they are, really. That’s the centre of what they are and everything else can radiate out from there.

It’s not beauty with Strawberry Switchblade, it’s haunting beauty isn’t it? It’s not great harmonies, it’s great requiem harmonies. There’s a sense of inevitability, a sense of patient holy longing. Waiting for something but you’re not sure what it is, and in the meantime you’re not quite in the right place at the moment in this life, that there’s something beyond that you’re reaching out for. And at the same time, you’re a young person trying to have fun, and it’s very difficult.

And so you’ve got to come up with a record that is like a bunch of young people trying to have fun, but with this sense of yearning and longing that we’re not really in the right place, we’re not settled.

Q: Why didn’t it work out with Robin Millar?

![Jill: 'That's in Stirling supporting the Farmer's Boys in 1983. Very very cold. The bass player was called John. I can't remember his other name cos I'm old and my brain's gone [John Cook]. He played with us with Simon Booth and Roy Dodds and we did the Robin Millar session with them.' 20 October 1983. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.](https://strawberryswitchblade.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/live_stirling83.jpg)

Rose and bassist John Cook, Stirling University, 20 October 1983. The band with Cook, Simon Booth and Roy Dodds played on the Robin Millar sessions. Hear and download the full Stirling performance in the Live Recordings section. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

Jill: Well I really liked it but the record company didn’t. They thought it should be more poppy, and we did too.

Q: Do you remember how the band felt at the time about it?

Robin Millar: No, because the wall went up. I assume whether out of disappointment, embarrassment or whatever it was, I simply never heard from anyone.

David Balfe: The sound was just a bit too gentle, a bit too soft, a bit too wimpy. It didn’t really have anything, it didn’t have any oomph to it. The girls were playing guitar live and stuff. It just wasn’t working. We were coming up with recordings, we went to Robin Millar, but it was like everything was too wimpy; the girls didn’t have the voice like Everything But The Girl and the songs weren’t as sophisticated as that.

John Cook: I don’t quite agree with Dave [Balfe], he calls a lot of it fey. Yeah the tracks are a bit fey but that can be appealing, that lightness of touch. I mean, Nico didn’t belt it out, did she? But she was an amazing artist.

Q: Do you remember when the sessions themselves were completed and you were listening back to final mixes, were people pleased?

Robin Millar: Well that’s usual. It was a fairly typical music biz scenario, really. There weren’t any people in the control room going, ‘well, it’s not really what we want and have you ever considered doing it with electronic drums or going in a different direction?’. No, it was all, ‘great great great, marvellous, this is brilliant’.

Then I heard they were in the studio with Dave Motion, the record came out, the record was a hit. There was nothing I could say about that at all, because that is the name of the game.

Q: Did the record company hold that much sway?

Rose: Well, we met loads of producers. We met all these guys, they’d come in and say ‘this is what we’re going to do’, and I’d think, ‘no, that’s not what we’re going to do, these are our songs, we have a concept, we created them and we want to see it through to the end, so we don’t want to just hand them over to you and say, here you go’.

There were a lot of producers we knew who were completely like that, who were completely the producer’s more important than the artist sort of thing, like he’s the artist. We met a few like that who we didn’t want to work with.

David Balfe: It just wasn’t working, so I had the idea of doing something a bit more electronic with it, contrasting their gentle acousticness with something a bit more oomph. Basically we were looking for somebody who’d take the songs and really give them arrangements which would work, and we found David Motion.

John Cook: We had a meeting with David Motion, I think we met him. I said I was planning on going to Norway skiing with my friend and he said ‘don’t cancel your holiday’.

And then we had another meeting when we hadn’t heard anything, which I think Simon must’ve called or pushed them into it – Balfe, Rose and Jill and me, maybe Roy was there, I can’t remember – where we heard that they were just going to work with David Motion, and he wanted to go in a different direction.

Making the album

Recording the Strawberry Switchblade album, Angel studios, London, 1984. Jill with guitar, obscuring Rose, David Motion sat at the desk, engineer Trigger standing beside him. Looks like Peter Anthony McArthur in the foreground, so photographer unknown.

Jill: So then we tried with this other programmer David Motion who eventually did the album, and we kinda liked him, he’s a funny guy.

David Motion: I thought they had a vibe, they definitely had a really interesting atmosphere about them, that sweet and sour at the same time kind of thing, dark and fluffy at the same time, fascinating. I found them very bright, very lively, and very very easy to get on with.

Q: What else has he done? I’ve never seen his name on anything else.

Jill: He’d worked – [giggles] he’d worked with Dollar! We were saying, ‘no way! No way! I don’t think that’s going to be quite us, is it? Are you really sure about this?’ And they were saying he’s a really nice guy. We liked David Motion when we met him, we got on well with him, we liked what he did, it was really quirky and kinda weird.

Q: It certainly is quirky to be given those songs and want to put really heavy distorted drum sounds on them.

Jill: Exactly. With every song we were like, ‘you can’t do that David, you can’t do that, what do you think you’re doing?’ We’d come in and he’d ask us what we think of a sound. Like Deep Water, we were like ‘what?’ But it was great, it just worked, and we said OK, let’s go with it. And we did a few and it was, ‘yeah, we like this’. It’s very 1980s when you listen to it now. Which is not necessarily a terrible thing.

It’s funny because we did try do play it down, try to keep it folky, keep it poppy-folky-jazzy, keep it quite innocent, quite acoustic, and it just didn’t work. We didn’t know enough about anything like that to be able to say what we wanted.

Rose: David Motion, he was meant to be a try-out as well, to see how it would go. I was quite unsure – I really liked David Motion, a really nice guy, he was really easy and pleasant to work with but I was really unconvinced at first because I didn’t like some of the sounds that were coming out. They were going ‘give it time, give it time,’ but the more time you gave it the more money was being put into the project and the more fighting you would have to do with the record company.

So in the end we ended up caught in that trap, basically. And in a sense as much as I love Motion I probably wouldn’t have gone that way.

David Balfe: The problem is that all musicians imagine they way something could have been, because they way it could have been was never done or judged. Believe me, I thought that was a far better album than at times preceding it I was expecting the first Strawberry Switchblade album to be. Yeah it’s got it’s weaknesses, but name me an album that hasn’t.

Q: What would you have preferred to see it come out like?

Rose: I would have rather it sounded less dated, I would have rather we used more real instruments, like Trees and Flowers for example with oboe and french horn. I know we did have that on some of the other tracks as well, people like Andrew Poppy did a couple of arrangements and David Bedford did another couple where we’d have an orchestra and that’s really nice. I would have rather worked with real instruments to be perfectly honest and not all synths and stuff like that cos it was not my passion at the time.

David Motion: We never disagreed in a major way. Occasionally it might be, ‘are you sure?’, that kind of thing, but I’d modify it. I never felt as if we were steamrollering them into something they didn’t want to do, I never got any sniff of that.

Q: Having heard the Radio 1 sessions and other early versions, the bombast of a lot of the released versions is quite overpowering by comparison.

Rose: I know. It was quite weird really, cos it was a medium that I wasnae that familiar with – synthesisers and stuff – not being very technically minded. I could work the mixing desk, I’d engineer for him and stuff like that cos I really liked doing that.

I do like synths a lot more now than I did then, I buy them now and I use them now. And there were some great sounds actually- I love that whale sound on Deep Water which was a synth sound. I love that sound, it gets you in the gut. I really liked quite a lot of it but there were bits of it that are too rinky-dink for me. You know what I mean? Like, press the sequencer and everything just goes dut-dut-dut-dut-dut, there’s nothing organic in there. Where’s the breath? Where’s the human in that? Everything’s digitalised.

I like analogue, although I use digital now as well, I do like that real feeling about music when you can actually hear somebody’s breath or you can hear them play the guitar, you can almost hear the fingers touching it.

Bill Drummond: I really really like early 1980s electropop. Vince Clarke period Depeche Mode for me is the best, when it gets heavier and [throws a sledgehammer-wielding pose] wallop, I don’t like it.

So I could see that that very light synthpop stuff could really work for Strawberry Switchblade as much as acoustics and stand-up bass. I do think on the whole that the album the songs didn’t work out. The songs were too delicate, they weren’t given enough space, the electro thing didn’t have that lightness that, in my head, Vince Clarke had right at the beginning of Depeche Mode.

Even though it seems I’m giving these negatives about the album, I also think the Since Yesterday single, it worked. And maybe there’s a couple of other ones that did work, when it was very sparse electro and stuff.

David Balfe: Again, I haven’t got a great memory of it all, but my memory is that everybody – myself and Jill and Rose – were equally extremely excited in a positive way about it. It was different, but that wasn’t a problem with me, I’ve always been into things radically changing as you work with them. And it suddenly made a lot more sense. It sounded commercial, the record company were excited about it and everyone felt strong.

Q: You’ve said that they were happy with what you’d done to the songs. Were there any of their ideas you didn’t go for?

David Motion: No, not really, because they’d always deliver them as, ‘well here are the songs’. It wasn’t that it was not under discussion but it was kind of ‘see what you can do with it’, and that was it.

My angle was very much that I was having fun and I’d come in one day and say, well, I feel a bit of Michel Legrand or something, so – what was that track that David Bedford did, the last track; Being Cold – so with that I just started and thought it could be a really nice Windmills Of Your Mind kind of vibe and it kind of grew from that and sort of seemed to work, and the melodica added to that sort of thing.

Q: Jill says she was actively discouraged by David Bedford from putting a melodica on it.

David Motion: Oh yeah! But I just thought that added the final touch. I think that’s the nice thing, you’ve got this quiet pro backing and this slightly ramshackle thing on top and that kind of gives it the edge.

The Phil Thornalley things [Thornalley produced Let Her Go and Who Knows What Love Is?], they’re a bit too polished. I like quirky stuff, and I wasn’t trying to thrash the quirkiness out of them, maybe that’s why that worked. Those kind of touches really helped, I think.

Basically everyone seemed happy with the way it was going. I did have a very clear idea about what I wanted to do, and I was always very interested in creating a very clear atmosphere, something very concrete something loaded and cool and with all sorts of interesting sounds. I was very interested in pushing the sonic side of it, lots and lots of processing, I was interested in mucking about more.

Rose: I would love to do that album again, I think those songs just weren’t done justice to. I don’t want to say anything that would reflect badly on anybody that was involved in it cos I liked everybody that we worked with, but I really think they weren’t done justice to, they could have been so much better if we’d gone with the same approach as Trees and Flowers and done it with real instruments, and we should have blended it a bit, but it all went dut-dut-dut-dut-dut. And some of the songs, my voice is so shrill, it’s really high and I just think, god, I sound like a chipmunk.

Q: But it’s that which gives it the fragility, the delicate touch. Harmonies build it up but it’s the high voice that creates that gorgeous fragile bit, that’s the thing that gives it its real sensitivity, its real power.

Rose: I like them, but I like them when they have a bass harmony down there somewhere. I like harmonies that are really close, that kind of resonate almost, like they’re the same organic thing. A lot of things I do now I like to put really close harmonies so it has almost a Gregorian feel. Then I like to put really high things over the top.

I want to record an album that’s all vocals, all the different melodies are vocal melodies. Maybe just a bit of simple heartbeat drumming a bit of flute or something like that, but mostly all vocal melodies coming from all directions. I really want to do that, something to completely surround your head and get drowned in.

Music is there to move you, it’s there to play with your emotions. Even when I was growing up the stuff I was drawn to was the stuff I could feel, it’s the passion in music – whether it’s tragic or beautiful or whatever – it’s that passion in music that makes music so powerful, which gives music the power over you as a human being.

Q: How quickly was the album done?

Photo from the session for the Strawberry Switchblade album cover, 1984. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

Jill: It took a while because we had all these stop-starts with other people. We went to lots of different studios, so it seemed like a lot longer than it was. He [David Motion] wanted to try out lots of different studios, which was fine by us.

David Motion: I have a very low attention span so I tended to work very quickly on it. We did the album in six or seven weeks, although there was a bit of pootling around at the end with a bit of remixing and that sort of stuff, it was essentially six weeks which was fairly quick at the time.

Q: Did WEA say to spend all that money cos it didn’t matter, you were going to be huge?

Jill: Yeah, they were ‘whatever’. It wasn’t budgetless, you know, and obviously he [Motion] wasn’t as expensive as Trevor Horn, and they weren’t overgenerous, but it certainly cost.

Q: Did much get changed that late on?

Jill: Nothing major. Since Yesterday we rewrote the verse. But that wasn’t him, that was us. We were sitting together and David Balfe was saying that we should think about the verse and rewrite it cos it was a bit repetitive, so Rose rewrote the lyrics. That was the most major change that we did. [The song was originally titled Dance, and had been recorded for the BBC Jensen session in October 1982]

Q: It’s the most prominent song on the album and yet until quite late the lyrics and melody were totally different. How late was it changed?

Jill: Pretty late, cos I remember Bill Drummond and David Balfe saying we should work on the lyrics. And not so much the lyrics but the tune to get more melody into it, a bit of variation. I remember her coming up and singing it and thinking it was much better, fantastic.

Q: Was it easy working with David Motion?

Jill: Dead easy.

Q: His work is so prominent on it, was there any kind of difficulty with how much he put in?

Jill: No, because we got on with him. We were kinda gobsmacked a lot of the time, but he always asked us. He wasn’t a man that you couldn’t approach. We trusted him and we liked him.

Q: Did you and Rose have much input into the arrangement of drums and bass and whatnot?

Jill: No, he did it.

David Motion: I would set up a song, record, which was actually quite hard cos when it started I was engineering it and producing it at the same time. At Marcus studios when we were starting certain tracks Rose and Jill weren’t coming in until after lunch, so if I were playing the piano or whatever then the tape op would be recording it and I’d be running in to listen to it. The initial arrangement was done quite quickly really. Then they’d come in and go ‘we like that’ or ‘we don’t like that’ or whatever; generally I found them incredibly receptive.

Rose: We could say yes and no to things. If we really didn’t like something we did have the power of veto. But also, there were so many bloody cooks in the kitchen, d’you know what I mean?

At first there was just me, Jill and David Motion, but then Balfe would come along and put his tuppence worth in and Drummond, and then the head of the company. But we did have a lot of control over it in the end actually, about how it was mixed and stuff like that, but if you’re having control over something you’re not a hundred percent in love with it doesn’t mean as much.

The one thing I don’t like about that is that the guitars are hardly audible at all. There are guitars on that album believe it or not, but they were mixed so low cos David Motion doesn’t like guitars, so low that Jill and I were almost mixed out of the album, apart from vocally. But it was that ‘just give it a chance, give it a chance,’ and then the album’s finished and you’re listening to it, and then what do you say? ‘I hate it, we’ve spent £250,000 and I want to do it again’?

It was so confusing, everything was going so fast, we were off doing this, off doing that, then back recording something else. It was kinda hard to be focussed on ‘do I like this or not?’, do you know what I mean? It was really confusing.

A lot of pushing and shoving was going on and I think Jill and I were wiped out by the workload we were doing. Especially when we were doing crap stuff, spending the whole bloody day doing a photo session, it was the most boring thing in the world. I didn’t mind interviews so much but I hated photo sessions.

Q: So the album’s done and Since Yesterday was the flagship single and the one really big hit. Anybody born between 1955 and 1985 and brought up in the UK has got to have wanted to be on Top Of The Pops. What’s it like going on Top Of The Pops for the first time?

Jill: It was dead exciting and absolutely thrilling, really thrilling. Really. I remember we went through it, the rehearsal was much worse that the actual thing. Once it all got going I just remember being ‘my god, what are we doing?’ Just being there, you know.

Q: Top Of The Pops was such an iconic thing. Maybe it’s changed now cos people are growing up with MTV and music television is freely available on tap, whereas at that time it was about the only thing apart from The Tube and Whistle Test.

Jill: I can remember seeing all sorts of people on it, and desperately waiting for it to come on, and we didn’t have videos so you couldn’t tape it when I was 14 or 16. You were there, you were waiting.

Q: And not only was it on rarely and not tapeable, but music was so central to youth culture up till the 1990s.

Jill: Any of it you did see you were glued to and everybody watched it. I remember as a young teenager watching Top of The Pops and seeing glam-rockers on it, T.Rex and Bowie, and when I was a bit older Be Bop Deluxe were on it. I really liked Be Bop Deluxe.

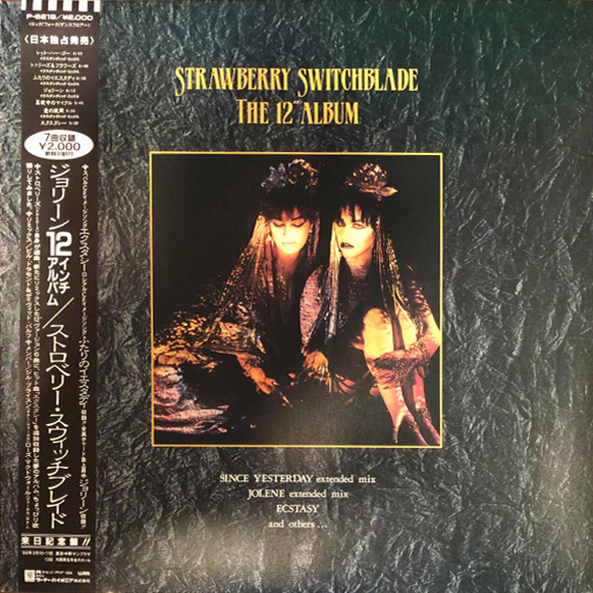

Videos, Jolene and overpromotion

Q: Having a hit certainly made the journalists attitude towards you change – most of the interviews after Since Yesterday is either trivial stuff about clothes, or it’s being patronising.

Rose: The press were up and down, really. It was good, we actually got loads and loads of exposure in loads of good magazines that were hip at the time. And then when we did Top Of The Pops it was Smash Hits and those kind of magazines. We did women’s magazines and everything, covering lots of angles.

Jill: The first interview we ever did was the NME about Trees and Flowers time, just a page [actually August 1982, nearly a year before Trees and Flowers]. The minute we had a single in the charts it was only about ribbons and what make up you use. Nobody really asked us anything, then they figured there was no depth to us so they wouldn’t ask us anything. How could it progress from that? People had made up their minds.

It was mind-numbingly boring. With most interviews you were shoved in a room for half an hour with someone so they weren’t going to get an in-depth interview, and you’d be doing it all day.

Rose: We’d get so bored with interviews like that that I started lying every time we did an interview. We did some women’s magazine, Women’s Own or something like that, and they said ‘what do you do when you entertain guests?’ I said ‘usually we have something healthy to eat, we’ll get some chips from the chip shop and some mineral water cos we’re really into healthy living. And then we’ll mudwrestle’.

They said ‘how do you do that at home’, I said you just get a big plastic pool, fill it with mud and have mudwrestling parties. They were ‘really?’ and we’re ‘yeah!’

‘and then what do you do?’ ‘Well, we shower off and have a glass of wine’. ‘Do you shower off together?’ I just said, ‘well, some of us shower together, some don’t, whatever’s easiest’.

Q: Did they print this stuff?

Rose: Yeah! They printed it, they printed it! In another one I said I was so exhausted I had to be carried out on a stretcher. My mum phoned me up cos they printed that. I used to just think, it’s time to have a laugh cos this is getting so boring. People can be so gullible – I would never have believed that in a hundred years – but they printed it! I thought they might leave out some of it cos it’s a bit risqué for Woman’s Own.

Q: Was there any opportunity to get taken seriously, if the proper music press is being patronising cos you’re not blokes and the rest is Smash Hits and Woman’s Own?

Rose: We did some interviews that were intelligent reading – I can’t remember what the magazines were – where there were some feminist themes coming at it from the angle of women in music rather than girls in short skirts.

Q: It’s an interesting angle to look at Strawberry Switchblade cos while it’s two intelligent articulate women writing their own songs, you’re also all ribbons and frills, and feminist politics at the time still had a big streak of not dressing up cos its got overtones of doing it just to please men, being a bit dungarees and crewcuts.

Rose: Well exactly. To begin with, in The Poems when I was an anarchist I went through a wee phase where I thought I shouldn’t wear make-up and stuff. Then I just thought ‘no’; that’s not me being who I want to be. I’m doing this because I like being extravagant and I like to paint my face like a picture. I’d do lots of colours or draw flowers on my face and things like that. I just like it, it’s an art form. Dressing up and doing this whole thing, it’s great fun. Kids love dressing up and I just never grew out of it!

If you’re a feminist it doesn’t mean that you have to be like a man, it means the exact opposite. People just got it wrong and thought you have to be as macho as possible or whatever. I was brought up with lots of brothers, I was a real tomboy when I was a kid; anything a guy could do I could do anyway, and I used to prove that throughout my growing-up years. I was always a feminist. If I want to wear make up and false eyelashes and whatever, so be it, nobody will tell me what to do.

I think a lot of feminists got it wrong, and because they got it wrong they probably lost a wee bit of the fun out of their lives cos they were taking it too seriously.

Q: Given that the record company start using their publicity machine, did they ever try anything more direct on steering your image? Did they ever say ‘don’t wear that, wear this instead’?

Jill: The record company struggled with us, but they couldn’t imagine doing it any other way. If they could’ve just cleaned us up, washed the make-up off and brushed the hair out a little bit, had the outfits but much cuter, got rid of the thick black eyeliner and blue lipstick, they would’ve done.

I remember they got a stylist to come up with some cute clothes; they were really nice, really well done, but they were cute and girly and frothy and sweet. Little strawberries on them and things. Good grief! What do you think we are?! She’d done this presentation with drawings and little bits of fabric, but well the whole point was we just shoved our clothes together, made them really badly, that’s why they look the way they look.

Rose: We were working with [director of videos] Tim Pope. I loved his videos and I just thought Tim Pope and us were a perfect combination, we had good fun working together. We talked to other video directors and they came up with the naffest ideas like Jill sitting on a bed with a box of chocolates and real girly sexist shit, real crap, no sense of art or anything, just boring video. That was one of the major upsets for me.

Jill: The shit videos we had to do! We did a couple of good videos with Tim Pope who was fantastic, such a brilliant guy, I really liked him. His birthday was the day after mine, I remember having a joint party. He was the sort of the person I wanted to work with. The first video he did with us I thought ‘he’s got it’.

Q: Which song was that for?

Jill: Since Yesterday. He got one of the animators from Magic Roundabout to do it. He shot it in black and white, we didn’t look particularly glamorous and we had polka dots on velcro so they could move about and the guy from Magic Roundabout animated us. There was a big pop-art hanging with circles, mobiles that spun, it was bizarre but so exciting. It took two days to do it cos the animation was so slow.

Tim Pope was such a nutter. It was incredible, really good fun and I thought ‘yeah, that’s great, that’s a really good video’, there was a point to making it.

Tim Pope: I thought there was something quite sinister and dark underneath the apparent fluffiness, there was something that drew me to it.

David Balfe: I thought it was a very big mistake we did. I thought it was a good video in terms of being entertaining, but it was just wacky. If you’re The Cure and you do something that wacky it’s one thing, but if you’re girls who wear polka dots and ribbons and you do something that wacky, it just looks wacky, it doesn’t look a kind of ironic-wacky, it just looks lightweight-wacky.

Tim Pope: I wasn’t particularly known for dealing with – quote – ‘women’. Whenever you make videos for – quote – ‘women’, as actually I recently did with KT Tunstall, so many people try and get involved with a video for a woman.

Jill: The second one he did was like a follow-on to it with a flurry of polka dots going off and they [record company] totally didn’t get it. It’s a bit more glam cos I think they’d told him to try and make us a bit more glamorous.

But Rose was just wearing this hilarious tutu and boots, we wanted it to look like something from Eraserhead, something really weird, something ‘these people aren’t quite right’, and the record company hated it.

We did another one with Tim Pope for Who Knows What Love Is? with us running about in costume in a park somewhere which was funny, and then they just wouldn’t let us use him any more.

Tim Pope: The record company, specifically this guy called Rob Dickins who managed the label, very specifically wanted them to be marketed like they ‘should’ be marketed, in inverted commas. He wanted them to be marketed like little girls, if you like. I thought there was something much darker, much more interesting.

And they felt very strongly, I remember this, they felt really strongly that they shouldn’t be marketed that way. They wanted themselves to be in the video, they wanted their personalities to be in it.

I think the first one [Since Yesterday] is the best video, definitely. I think the next ones are OK, they sort of have a magical quality which I think are nice. I was still inexperienced in those days as well, I was still very much learning, and unfortunately learned sometimes at other peoples’ expenses!

I think it’s quite quirky that one still [Let Her Go]. Funnily enough I hadn’t seen it for years and then maybe I saw it on your site, I hadn’t seen it for about 25 years or something and I suddenly saw it and I thought it was pretty shit actually to be honest, but I could see what I was trying to do. It had a sort of dreamlike thing. There’s that bit where Jill leans over where she’s a bit sort of mad which I liked.

Q: For Who Knows What Love Is? there’s all the outdoor sequences. Is that consciously trying to make it different from the first two?

Tim Pope: No, I would never work that way. I thought the song had a very dreamy sort of sappy quality. There was something very sexy about the two of them as well, and I used trees and things like that, and there’s this overt sort of sexual almost lesbian thing that happened in that, in a very dark and bizarre way. There’s this idea of Rose stalking Jill and all that kind of stuff, and coming between that big tree, I thought that was a real old chuckler. It was just me having a bit of a chuckle to be honest.

We just ran around with a 16mm camera. There was a cameraman I had met in that period who was an art student or something and I liked the way his stuff looked. We just thought we’ll fuck off to this forest and shoot all this dark stuff. The light was brilliant that day, it was really magical. I remember the rushes of that were really magical and quite dark.

There wasn’t really anything to make a video for after that was there, apart from Jolene.

David Balfe: Once you’re a pop band that doesn’t have hits it’s all over. I think we gave it one shot after we couldn’t work out what was wrong with the second single, and then we were into desperation mode for I don’t know how long before Jolene came out, and that was just a real desperate thing. If you could get back in the top ten you were back in the game, and if you can’t, we knew it was all over.

Q: How did the Jolene single happen? Why that song?

Jill: [laughs] Well, we were just desperate by that point. They wanted us to do something like that.

Q: Who suggested it?

Jill: You know, I can’t remember, I think it might have been Balfey.

Rose: It was Bill Drummond. Loved the song, loved Dolly Parton, thought ‘you have to do this song’.

Bill Drummond: That was a definite record company thing.

David Balfe: Jolene had come from the girls and their boyfriends. I think it was Peter, Jill’s boyfriend, said ‘why don’t you do Jolene with an I Feel Love backing thing?’. We had a John Peel session or a Kid Jensen session or something like that, and we went in and I programmed a thing to go dududududu [I Feel Love bassline] and you can actually sing Jolene to that and it worked great, and we did it. [BBC Radio 1 session for Janice Long, recorded 27 September 1984].

Then we took it into the record company and said ‘this could be a good single’ and we got a guy [producer] Clive Langer in to do it. For some reason – which I argued with him about but he insisted on it – he changed it from that I Feel Love thing that could have worked in a disco to this dun-de-dundun-dun thing. It sort of sounds like some programmed hopalong cowboy beat. I think he was probably too scared of doing a straight pastiche of I Feel Love. It’s quite a modern phenomenon now, bunging two things together, and we liked that.

Q: Rose said it was you that had the choice of song.

Bill Drummond: She really liked Down From Dover. She came to me and was talking about Dolly Parton, she was a big big Dolly Parton fan and I think they already did this version of Down From Dover themselves, it was a cover version they would do. So it was borne out of the fact that she was really into Dolly Parton and they did this Down From Dover song. So we said, ‘do you want to do Jolene?’. So that’s how that came about. [In 1993 Rose released a cover of Down From Dover on the Spell album Seasons In The Sun].

Rose: And that was another thing – we should have gone for the Marianne Faithfull one when they wanted us to do that. They wanted us to do a cover.

Q: Which Marianne Faithfull song?

Rose: The Marianne Faithfull one was put to us much earlier on, it was As Tears Go By, which is a beautiful song and I love it. I actually have done a version with Dave Ball which was not released, but we did a version of it.

Rob Dickins loved that song and wanted us to do a version. I think it was just after Since Yesterday or something like that, so we didn’t want to do a cover that soon cos then we’re going to get into the covers thing, and we want to our own songs, so we bluntly refused that.

But then after a couple of other singles the Jolene thing came up and that was one of those ‘you do this for me I’ll do that for you’ things. Things were all falling apart by that time, we couldn’t use the video director we wanted.

I actually liked the song Jolene and I liked Dolly Parton, but it was still a trade-off and I was anti it purely on the principle that it was a trade-off. They wanted it to be a club thing and I wasn’t into that scene at all. I didn’t care if the records got played in clubs. We’re not releasing records to be played in clubs, we’re releasing records cos we’re musicians and that’s what we do. They wanted to do it cos it would make more money and blah blah blah.

Jill: We thought OK, that would be really funny because we could do it really camp and we wanted to do this really camp video and we had it all worked out and they didn’t let us do it.

We had to go to Paris to shoot it and it was terrible, sooo embarrassing. I can’t even tell you, it was just shit, just awful, really bad. We wanted it to be shot in a fake saloon with busty barmaids with plumes and cowboys and stuff, we just thought that’d be so funny. Really crap, bad shaking saloon doors, really tacky, really colourful so there’s no doubt in your mind that this is fun and something daft. But no.

Q: It’s really odd as a counterpoint because there’s such melancholy to your own songs.

Jill: I don’t understand it myself really. We liked it, but we liked it the camp silliness of it, and it was such a silly thing to do

Q: Especially trying to see it as being of a piece with everything else you’d done before.

Jill: Exactly. And also the way it was done, which was Balfey. There was a lot of Balfe influence, I remember we did the recording at AIR studios in Oxford Street which was very expensive and there was a lot of muso people involved, it was nothing to do with me.

By that time I thought I don’t want to do any of it, I just want to go home, go back to Scotland and lie in a darkened room and pretend it hadn’t happened.

David Balfe: Now we get to the difficult more controversial bit. Things were still running on and the record company were losing their faith now, I think. Time goes on and you’ve budgeted for a year or eighteen months of costs.

At some point I had to say to the band, ‘I’m going to have to stop your wages in however many weeks, and also paying for your flats. You’re going to have to think about what you want to do cos we’re running out of money and I can’t get any more money out of the record company’.

They were saying ‘we really really don’t want to do this, what can we do?’ They had some money put aside for tax, and I said ‘you can spend your tax money if you want, but it’s a big risk; you wouldn’t have anything put aside to cover everything’. And they insisted that they did that, they didn’t want to go on the dole. I advised them strongly against it.

They started arguing about things – I can’t even remember the specifics, it wasn’t any big musical differences. Although Rose was hanging out with people like Genesis P-Orridge who I found a little bit too weird even for my taste. They were each complaining of the other, although mainly Jill complaining about Rose.

Q: About what?

Off duty during the second visit to Japan, March 1986. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

David Balfe: I can’t remember specifically. It always happens, when things start going wrong people start having plans for how to fix it and people are less likely to agree about it. When things are going well people always have ideas but they don’t really get upset, everybody says yes to everybody’s idea. When things turn to difficulty then ‘ideas’ become ‘solutions’, and solutions are something you desperately have to get everybody on board for.

Rose: So that’s when it started falling apart basically. That whole Jolene era was too many compromises and not enough comebacks.

Q: Did both you and Jill feel like there were too many compromises?

Rose: Yeah, I think so.

Jill: I remember the worst thing, the thing where I thought ‘I don’t want to do this any more’ was round the time of the third single. The second single [on WEA, Let Her Go] hadn’t gone into the charts and so they really wanted to push. They wanted me to go out with Mike Read [then Radio 1’s inane breakfast show DJ and twattish TV ‘personality’, not to be confused with Mike Reid who played Frank Butcher on EastEnders, arguably an even grislier sexual prospect].

Mike Read used to turn up at things, he’d turn up at studios. They’d obviously told him where we would be, and I was not interested, they knew I had a boyfriend. The promotions departments in record companies seem to be peopled by folk with no morals, they just want you to do anything. And I said no. The mind boggles cos we weren’t exactly glam pretty girls, we were weird hair-extension freaks.

I remember going with the radio promotions – radio promotions seem to be the worst – to Langan’s Brasserie, that posh restaurant, to have lunch with Mike Read, ostensibly just to chat, and it was with Rose and Balfey and radio promotions guy and I’m like ‘I’m not sitting next to him, you’re not putting me next to him’. And they put me right next to him. Can you believe it? Just for publicity, let’s get a photo. That is not why I was doing it, and I thought fuck it big time, I’m not doing it, that’s not what I want to do. And at that point I was not getting on with Rose and her kind of losing proportion of the whole thing.

Q: In what sense? What kind of thing?

Jill: We just kinda went off in different directions. She did lose proportion. There was obviously a lot of pressure and she just wasn’t used to stuff like that and she didn’t know how to handle herself and she was greedy. She was ‘this is my thing, it’s not yours, just keep in the background’, you know? Which is tiring after a while, you need a bit of mutual respect if we’re going to do this.

I mean, I know a lot of people in bands hate each other but there’s still some kind of respect there that holds them together and makes them recognise what the other’s doing is good. By the time it got to this stage I couldn’t even recognise that, it was just silly.

David Balfe: When you’re new to a relationship people tend to club together. They were in the group, they knew each other, whereas I was this guy from the music business who’d been in bands that were successful and stuff. I think they were a bit intimidated by it. So they present a front to you, so you’re never quite sure as the front evaporates over time and you start to see the way things are; is that the way things have always been or is it the way things have gone over recent times?

They worked very closely, it was a bit of a classic sort of Lennon and McCartney thing insofar as when they started I think they were very much excited by working together and fresh, and then as they progressed it became that it’d be one person’s song or the other, I think. The initial songs were, as much as I could see, worked on together. And they were so friendly with each other, there was not a lot of differences you could generalise about. While Rose was far more the tougher character, they both kind of wanted to do what they did.