David Motion (producer) interview

2 August 2002

Composer and producer David Motion took the helm for the Strawberry Switchblade album.

Motion’s Soho studio has a large open wooden floor and banks of very expensive looking equipment with blinking lights. It is probably to do with making music but looks like you could put wings on it and fly it to the moon.

He gets out a white label test pressing of the Strawberry Switchblade album in its original running order. He clears the CDs from the top of his turntable (like most of us, by the early 2000s his record deck had become a table for putting CDs on), and we go through the album.

It runs:

Side 1

Since Yesterday

Deep Water

Poor Hearts

Another Day

10 James Orr Street

Side 2

Go Away

Who Knows What Love Is? (David Motion version)

Little River

Secrets

Who Knows What Love Is? (reprise)

Being Cold

His set up has the kind of speakers you get in professional studios, the kind that are at head height and make anything sound like the voice of god. Hearing the David Motion version of Who Knows What Love Is? for the first time here, at a volume where we have to shout to be heard, is an extraordinary moment.

Before

Q: How did you get the job of producing the Strawberry Switchblade album?

Q: How did you get the job of producing the Strawberry Switchblade album?

I was in a band, Home Service, years and years ago, and basically I fell in love with the recording process. I thought I’d get into studios to learn how to do better recordings of our own material. The idea was that in down time I would record stuff for our own band. And then it took off, I was working 36 hours a day and things moved very quickly. I was in an eight-track studio in Kingston and then somebody there said they’d introduce me to this 24 track near the airport called Airport Studios.

Q: When was this?

It started in September 1982, I was 23 at the time or something like that, fairly young. The idea was that I’d be a pop star, that was what I wanted to be, like everybody else.

Q: What genre were you?

Technically it was techno-pop, although really without much technology. It was New Wave. I arrived in London and studied at the Royal Academy of Music when I was 18, that was 1978, and just missed the punk thing. But then the stuff that we were doing was on the back of that, it was New Wave. Very influenced by things like Kraftwerk and Yellow Magic Orchestra, early Human League, stuff like that. Cabaret Voltaire, everybody was listening to that at the time.

So I was at the Academy and then I got booted out after two years cos I just wasn’t doing the work and I had a colourful home life at the time. Also I was very interested in pop music, I’d always straddled pop and classical – as I do to this day – so I was torn. The Academy was very much, like, Elgar is the most modern thing there is as one faction, and the other faction was squeaky-gate stuff like Stockhausen, Berio, who were totally atonal. I didn’t fit into either of those genres. But they did have a little studio in the Academy, a tiny little 4-track system and I just went in there and recorded stuff and succeeded in blowing up the desk on a couple of occasions.

At the end of the second year I gave them a tape, it must’ve been about an hour’s worth of music, which was all sopranos and white noise with sweet piano behind it, tuned noise but quite tonal. They said, ‘well this is all lovely but we want you to write this piece for bassoon and piano like we asked you to, and if you don’t then don’t bother coming back’. So that was the time I thought, forget that. I went and got a job and did the band on the side of that.

After a few years of that we did a few gigs, made a few records on our own label, got played by John Peel, ran this little label out of our living room in Tottenham called Crystal Groove records. By about the third record we were getting quite sophisticated, already spent a little bit more time in the studios cos I’d started engineering.

We got one record released by Situation 2 who were part of Beggar’s Banquet, a track called Only Men Fall In Love. By that stage the drummer and I had got rid of – god that sounds really patronising! – we’d gone more techno-pop and decided guitars weren’t part of that. We were a four piece, there was a keyboard player/singer, a drummer, a guitarist and a bassist, and that was the line-up for the first two records, which was very much in keeping with the New Wave format. Then we got more and more involved in the recording, the idea is that there’s just a recorded record, it was just synthesisers and vocals and drum machine.

With that running alongside, I got into studios and that took off and I learned very very quickly. I actually managed to blag the job in the first place, it was a bit bizarre but it shows what can be done if you really really want to do something. This studio in Kingston, I had a friend – who many years down the line ended up as an A&R person at WEA quite by coincidence – who said there was this eight-track studio in Kingston called Ark and I happen to know the owner is really pissed off with his engineer; the guy is unreliable, flaky, probably charging more than he’s declaring, that sort of stuff.

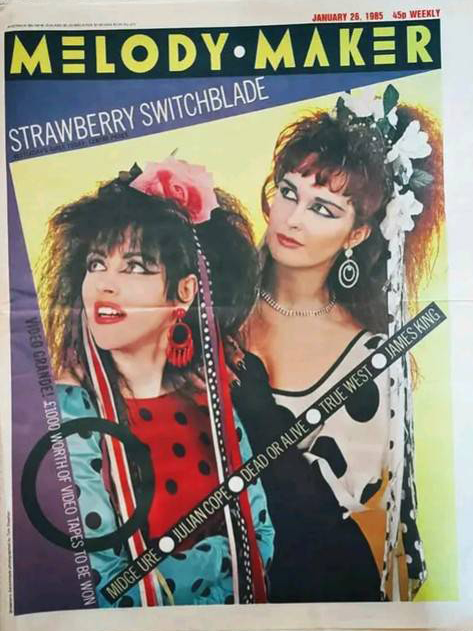

First ever Strawberry Switchblade gig, Spaghetti Factory, Glasgow, December 1981. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

So I just wrote a letter saying how punctual I was, how methodical, trustworthy, all that sort of stuff, and I got a job. The thing was that I hadn’t actually been an engineer ever before. In those days in Melody Maker they used to do articles about studios, and I got hold of one about this studio and it had a complete equipment list. I sent off to all the manufacturers asking for brochures of those bits of equipment and sat down and tried to figure it all out. I’d never actually used the gear before.

It was tied in with a little bit of looking over people’s shoulders when they were making our records so I had some sense of it, but still the first session I had with people paying was pretty hair-raising. But I learned pretty quickly. The bands tell you what they want. I did one session early on where I learned so much, a bunch of black guys in a reggae band, twelve guys in this tiny room smoking weed. They were saying, ‘no it’s wrong, it wants to be more like this’ and I’d turn the graphic EQ and go ‘that?’ and they’d say yeah; I learned like that. Then after a while you get used to tuning into records and the sounds other people use.

So I was six months in this eight-track studio, I got poached by the 24-track studio, and one of the bands that came had a friend at AIR studios, a technical guy, so I had a meeting at AIR. What I didn’t realise was that they offered me the job of assistant engineer, so it was a tape-op, it was going back several steps for me. It was quite useful though cos it meant I could look over the shoulders of the top people at the time.

Ironically Phil Thornalley was one of the first sessions I tape-opped on [Thornalley was brought in to re-record Let Her Go and Who Knows What Love Is? on the Strawberry Switchblade album after the record company rejected Motion’s versions]. He was doing a Thompson Twins mix with Alex Sadkin. It was amazing just to see how people at that level worked. I did a lot of stuff with Chris Hughes and Ross Cullum, I tape-opped for Martin Rushent.

Q: Jill said you’d previously worked with Dollar.

I worked with them separately after they’d split up. At AIR I did a remix with Thereze Bazaar. I found her slightly harder to work with cos she had worked with Trevor Horn and was doing her remix with this ‘I’m The Producer’ vibe about her.

I worked with David Van Day with Wang Chung. This was slightly before Strawberry Switchblade. Wang Chung had written a song for him. They got me in to engineer this thing, we did it at Marcus studios. David Van Day is a very very nice bloke, very amusing person, but he really could not sing to save his life. We were recording his vocal and he just could not get it, just could not get it.

At Marcus there was a vocal booth with a piano in it which you couldn’t see into from the control room, which was very very necessary. We had to have him off to one side out of sight, because he would’ve found it demoralising had he seen the efforts we were going to. It was in turns exasperating and amusing.

What we resorted to doing was running the tape, take all the backing track out of it, and at a particular moment Jack would play the piano and sing the line before and I’d bang it into record and David would try and mimic what he just heard. It took days and days and days to get four lines of vocal which were really not that hard. It was scary. I’d be punching in on individual syllables.

The amazing thing is that once you did actually piece one together out of sixty odd takes it sounded a million dollars. But god it was hard work.

At the end of doing this track we went to a Japanese restaurant and we all got quite drunk and David was saying he didn’t want to be a singer anyway, he wanted to be an actor. I can’t remember if he said he’d been to RADA [Royal Academy of Dramatic Art] but he’d certainly been to some acting college. And then proceeded to spout Shakespeare at volume. Just before we asked for the bill he gave it the whole ‘now is the winter of our discontent’, doing a good thirty lines of it.

At the same time I was at AIR I was still producing on the side in smaller studios for Cherry Red and people like that. Did an album for Kevin Hewick, there was a band called Swallow Tongue I did a 12 inch for. I was just working stupid, stupid hours, doing a full day at AIR and then sessions elsewhere on these other bits, so I was quite fried, which was another thing that made me want to move on pretty fast.

So I left AIR and about a month afterwards I got a call from Max Hole who was Chris Hughes’ manager. Chris Hughes was the producer of Tears For Fears. I tape opped on a session he did for Wang Chung.

Q: Was it unusual for a producer to have a manager?

No, it was quite common in those days. I didn’t have one at that time, but I wasn’t a big name producer. It was quite common; I got a manager in ’86. The second you have any sniff of a hit they call – I had calls from about 25 managers, it was a real eye-opener, quite fascinating.

Chris Hughes produced Adam Ant early on – Kings of The Wild Frontier, the hits – and he was also a drummer so he was rhythmically very very good. He hooked up with an engineer called Ross Cullum and they were notorious for how long they took over things; that was an eye-opener as well. At AIR studios they were doing a few overdubs for one track, Dance Hall Days by Wang Chung, and then mixing. The mix took four days, and two and a half days of that was basically spent on the bass drum, getting the sound just right. That’s symptomatic of the way it was all going in the 1980s.

I learned quite a lot just looking over peoples shoulders; Martin Rushent had a particular system of how he worked, Chris Hughes had a system with his Fairlight and stuff like that, a lot of triggering going on A lot of time was spent on things, and it was very difficult to keep your objectivity over that length of time.

So Max Hole, Chris Hughes’ manager, also happened to be the head of A&R at WEA Records, which was quite handy. So he phoned up and said, ‘Chris Hughes said you were great, why don’t you come in and do a meeting?’. We did a meeting, and at the time I had no idea how powerful or important it was, you know, Rob Dickins was there as well, and they said, ‘we’ve had this idea, we’d like to offer you a contract as a staff producer position’. I’d never heard of that before.

Q: It’s the kind of thing Motown did in the 1960s.

Exactly. And WEA when it was Atlantic, all those people had staff producers who would produce all the stuff. It was great for me. The idea was I’d produce two singles and two albums as part of this year-long deal. I did two tracks for Black. It was clear they were going places, but then wasn’t really the moment. I can’t remember what else I did. Then it was Strawberry Switchblade.

They said, ‘we’d like you to come and meet Strawberry Switchblade and we’re very keen for you to work with them’. I don’t remember being on some kind of shortlist or anything.

I think the idea was we’d work on a track or two and see how it went, and if it worked out it’d lead to an album. At the time Balfe and Drummond were also A&R and had this kind of unit, they were on the same floor as Max Hole and Rob Dickins and Paul Conroy. I can’t remember the exact relationship. They were technically A&R, but they were also Strawberry Switchblade’s managers.

From the photo session that yielded the Trees and Flowers cover picture, 1983. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

I remember them saying they’d done this indie release, released it on a friendly label or whatever, but it is seen to be coming out of the underground for it to be authentic and all that. And they thought they could do something more.

Q: Had you heard any of the recordings then, the BBC sessions or the indie single?

I don’t remember the BBC sessions, I remember the single. They were more interested for me to hear the next set of demos. The demos were very much along the same lines, quite indie, guitar and vocals. At that time I was really more interested in fashioning pop. Not necessarily commercial – although I have some commercial instincts I still think I am quite left of centre and quirky.

I thought it was great to be working with people who allowed me to do all that other stuff. I’d get the demo, listen to the track, figure out what the chords are and build it up from there. Obviously respecting the integrity of the top line of the melodies, I don’t remember touching those in any way.

In that early period I remember them coming to my flat in Tottenham, we’d borrowed a synth and we kind of thrashed around a bit with that and a drum machine that we may even have borrowed from Balfey. I mapped out one or two of the songs, then we started recording, then it just sort of developed into the album.

I was very keen to do a week at a time in different studios. Partly for my own experience, to play the field and find where the good studios are, and it was something quirky as well to keep changing the landscape, having been stuck in AIR studios for several months. I wanted to try out all these other places that I’d heard of, so that’s exactly what we did.

I would set up a song, record, which was actually quite hard cos when it started I was engineering it and producing it at the same time. At Marcus studios when we were starting certain tracks Rose and Jill weren’t coming in until after lunch, so if I were playing the piano or whatever then the tape op would be recording it and I’d be running in to listen to it. The initial arrangement was done quite quickly really. Then they’d come in and go ‘we like that’ or ‘we don’t like that’ or whatever; generally I found them incredibly receptive.

Q: What were your first impressions on meeting them?

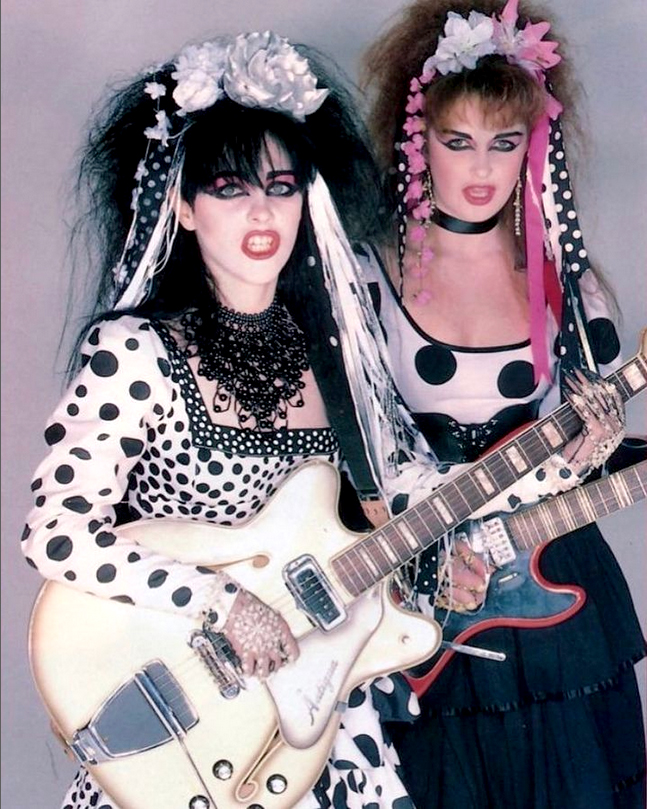

I thought they had a vibe, they definitely had a really interesting atmosphere about them, that sweet and sour at the same time kind of thing, dark and fluffy at the same time, fascinating. I found them very bright, very lively, and very very easy to get on with.

They did give me an awful lot of control. There was an awful lot of trust. It was fantastic for me, really. Everybody was saying greatgreatgreat and just letting me get on with it. They’d come in and say, ‘that’s great’, and as time unfolded and we finished things – I can’t remember if we finished Since Yesterday before the rest of the album or what – they started getting the marketing department and the promotions department taking up more of their time. We were having to carve out time for them to come and do vocals. But it all worked very well.

Recording the album

Promotional photo, c.1984. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

Q: What you did to the songs was such a departure from what they’d done before. Did they have any reservations about any of it?

Not that I was aware of. Whether or not it was something I was ignoring in the general euphoria of it playing out that way and me having this enormous freedom, but basically everyone seemed happy with the way it was going.

I did have a very clear idea about what I wanted to do, and I was always very interested in creating a very clear atmosphere, something very concrete something loaded and cool and with all sorts of interesting sounds. I was very interested in pushing the sonic side of it, lots and lots of processing, I was interested in mucking about more.

I have a very low attention span so I tended to work very quickly on it. We did the album in six or seven weeks, although there was a bit of pootling around at the end with a bit of remixing and that sort of stuff, it was essentially six weeks which was fairly quick at the time.

We never disagreed in a major way. Occasionally it might be, ‘are you sure?,’ that kind of thing, but I’d modify it.

Q: Both of them remember it being a very easy very smooth working process.

It was. I never felt as if we were steamrollering them into something they didn’t want to do, I never got any sniff of that.

Q: You’ve said that they were happy with what you’d done to the songs. Were there any of their ideas you didn’t go for?

No, not really, because they’d always deliver them as, ‘well here are the songs’. It wasn’t that it was not under discussion but it was kind of ‘see what you can do with it’, and that was it.

My angle was very much that I was having fun and I’d come in one day and say, well, I feel a bit of Michel Legrand or something, so – what was that track that David Bedford did, the last track; Being Cold – so with that I just started and thought it could be a really nice Windmills of Your Mind kind of vibe and it kind of grew from that and sort of seemed to work, and the melodica added to that sort of thing.

Q: Jill says she was actively discouraged by David Bedford from putting a melodica on it.

Oh yeah! But I just thought that added the final touch. I think that’s the nice thing, you’ve got this quiet pro backing and this slightly ramshackle thing on top and that kind of gives it the edge.

Going back to the Phil Thornalley things, they’re a bit too polished, it might not have been the right song, I don’t know, but maybe people sense if it’s not quite real enough. I like quirky stuff, and I wasn’t trying to thrash the quirkiness out of them, maybe that’s why that worked. Those kind of touches really helped, I think.

It was nice to have those little bits of orchestral stuff on as well. I was doing lots of stuff like triggering white noise and tuned noise and stuff like that on 10 James Orr Street. On my version of Who Knows What Love Is?, which you can hear on the reprise, it got quite in deep with the sampled brush sounds, stuff like that, each with their own slightly different reverb and positioning, that took quite a while to construct.

And then there was this trumpeter Bruce Nockles; I was very keen to have a texture, there was something kind of missing, so I just sent him out and he said ‘why not just do some long notes?’ and then it was ‘yeah that’s great, but can you do more different ones?’, so there are these clusters and this slightly drifty backing.

Q: How much were WEA watching over your shoulder?

Not that much, really. I mean, they’d pop down from time to time. We did a week in [rural residential studio] Chipping Norton and that was fairly close to the end, and I think I might’ve arranged it like that cos I didn’t really want them to come down that much. It was harder for them to do that if we were at Chipping Norton.

I think we did a week at Martin Rushent’s place as well, at Goring [rural Berkshire]. It wasn’t actively to discourage people from coming down, they were welcome whenever. They didn’t really come down that much, they were really just listening to the end result and saying ‘that’s great’ or ‘no it isn’t’.

The moment that it really happened was with Since Yesterday. We did two mixes that were not quite right. The third one was the one, and that was a long mix, three days. By that stage we were also working with Trigger as engineer, and we were kind of trying to come at it more radically.

Q: It is a very odd sounding record, even in the context of the album, it’s not conventional pop by quite some way. The hardness of the drum sounds is really arresting.

Well that was one of those moments, we’d been working away for three days and we were determined to try and get it to work. It was quite late at night, I was saying to Trig, ‘it’s not quite right, let’s pull the faders down and start again’. We started with the drums and he was EQing the snare and he just said, ‘maybe it should be something like that’ [turns hand vigorously], and there was this moment we went, ‘yeah! That’s it!’

It was very mid-EQ’d, a short bandwidth so although there was a lot of top on it there wasn’t much bottom, and from that everything else slotted into place, the bass drum and snare just suggested everything else. The stuff was already on tape, but it was possible to cut away all the unnecessary stuff and it became very clean and angular, everything was there for a reason and Rose’s verse vocals just sail over the top of it.

And then there was a moment of ‘what the hell are we going to do with the middle eight?’. It was basically the same as everything else. That was another three in the morning one, I said, ‘why don’t we try gating it off the hi-hat, gate the whole track?’ That was fairly radical, and it was born slightly out of desperation!

Recording the Strawberry Switchblade album, Angel studios, London, 1984. Jill with guitar, obscuring Rose, David Motion sat at the desk, engineer Trigger standing beside him. Looks like Peter Anthony McArthur in the foreground, so photographer unknown.

We were pissing round, but we were having such fun cos at that point the rest of the track was in place, everything was happening, there was just this one section that wasn’t up to the same level as everything else. So we tried that, and that was it, it just sounded great.

I remember thinking we thought it was great, but then thinking it might be a bit dangerous for the record company. We had no idea when we sent it off and all went to bed at six or seven in the morning. And then at eleven or twelve o’clock I got a calls from everybody, Max phoned, Balfey phoned, Drummond phoned, saying there might be a couple of minor reservations but it’s fantastic. So I thought, yeah, goal!

Q: The song itself was rewritten quite late on, the version you would’ve heard on Peel sessions or demos would have been called Dance, which was substantially different.

I didn’t realise that. It’s possible she said, ‘I’m going to rewrite it’ and when she sang it it just sounded so natural, but I can’t honestly remember that.

I remember doing something I did an awful lot at the time, at the end of a track to have all the vocals running at once for the end choruses. I think they really enjoyed that because all of a sudden it takes it to another level and you can see how everything fits nicely together, you get extra texture. I think it was something they hadn’t really come across before. It worked really well, you just ran a section of the verse vocal while the chorus vocals go on at full tilt.

Part of what I did with a lot of it was just change. The chords were always fairly straightforward, the song came as them doing a demo, demo vocals sometimes with incomplete words and very straightforward guitar chords. Nothing wrong with it, but a lot of what I was doing was changing it so there was a lot of substitution so it’s not just E or A or whatever, putting different things in the bass, just to make it all flow a bit better and have a bit more colour and texture.

I can’t remember the process for that, but it was a very evolutionary thing. Things would get chopped around a lot as well, partly by the way that I was working in the studio. It was quite techno, in the sense that we were using a lot of technology, but it was still very early technology, so it was very early sequencing.

A lot of the stuff was triggered – and this is stuff I’d picked up from people like Martin Rushent and Chris Hughes when I was tape-opping at AIR – where you put linn drum code down and fire samples off that. Sometimes there’d be delays and the linn code would be before it by a second or something and you’d have to have a delay for the sample.

So you’d put down the linn drum where you wanted it to start, just as a reference point. Then you’d load a sample of a particular drum sound into an AMS, which was a delay at the time, trim that down and then that would always be slightly late, so you’d have to turn the tape over to measure how far you were out. You could do it by ear if you like, but if you were doing it methodically you’d measure it so you’d get it bang in time. It was painstaking stuff. I’m amazed it only took six or seven weeks, that was quite quick considering the technology.

Jill Bryson and Rose McDowall, Angel studios, Islington, London, during the recording of the Strawberry Switchblade album, 1984

And then there was some early sequencing. I can’t remember the name of the sequencer, but there was a guy called Gary Hutchens who I worked with a lot round that time. This is pre-computer as well, before Cubase and stuff like that.

Everything else had to support that, but it wasn’t like a guitar band, it’s not like we’ll play this live. You kind of build a concept and graft this on to that, but I always believed about production that you want to leave somebody with a very clear impression after they’ve heard it, even if they can’t necessarily remember the melody you want to leave them with a very clear sense of atmosphere. And the atmosphere needs to kind of match what they look like and what they’re trying to project.

Q: How do you remember the working relationship between Rose and Jill?

Very friendly, very kind of tight. They seemed very close. The more I got to know them the more I realised how different they were. They seemed to get on really well, I never really saw them argue but they were coming from slightly different places I think.

Rose was always slightly kind of – you can see it in the vocals – her vocals are harder, possibly less… if I say ‘sentimental’ it sounds like I’m saying Jill’s are sentimental which they’re not, but Jill’s were always softer and sweeter and that’s why quite often she would be doing the chorus ethereal stuff, Jill’s was always more logical and Rose’s voice would always cut much more. That’s how they were as people as well.

I never really saw them arguing, they seemed quite close. They also had their support network as well, ‘entourage’ is a strong word but Jill’s boyfriend at the time, Peter, was with her everywhere. With her agoraphobia and everything, she would appear in a cab and then he would always be around. I don’t know if [Rose’s husband] Drew was around that much, but there was a sense that it wasn’t just Rose and Jill, there were other kind of lobby parties around.

Q: Did it seem like an equal partnership between them?

It did to me. I was very keen for there to be a good relationship amongst the three of us, but I always saw them as presenting a fairly unified front. I don’t remember thinking, ‘if I can get Rose on my side on this one we can get it through,’ or it ever being anything like that. They seemed to be getting on really well, and be having fun also with the forthcoming success.

I think they did get a little frustrated with the lack of time they had. The cabs would start to arrive later. That was such a record company thing in those days, instead of travelling by tube or any other way it’d always be a cab from home, a cab back. They’d have more marketing meetings and have to go, as it got closer to the end there was more of that which had an impact on our time. Which gave me space to do even more stuff.

There was a residual thing about the album, that Rob Dickins was saying about my sound basically, which was that it was incredibly bright and it hurt his ears and there was no bass and stuff like that. Which I don’t think is really true, although I was very fond of that kind of that really bright, jangly, angular kind of sound. Which is why Phil Thornalley did a couple of tracks on the album. Obviously I’m bound to say this, but I still think my versions are better, but his were much smoother and more commercial really.

Q: I was just about to ask this, what brought Phil Thornalley in?

I think because of this residual thing that somehow my sound was a bit hard. They – that’s Rob and Max – were obsessed about things crossing over into the States. I’m not sure Strawberry Switchblade were ever a Stateside proposition.

Q: I don’t think anything was ever even released in the USA.

No, but they identified that if it was smoother and a little bit softer it might work better for the States. We did have this ongoing tension between us, Rob and Max versus myself, about the sound. I loved it, the brighter the better as far as I was concerned at the time but, as I said, I did have my own agenda. So he [Phil Thornalley] was brought in and he did Jolene and he did…

Q: It was Clive Langer did Jolene, Phil Thornalley did Let Her Go and Who Knows What Love Is?.

Yeah. My version of Who Knows What Love Is?, there’s the reprise at the end, which forms the basis of my version. I only just relistened to it today for the first time in five or six years and a lot of the arrangement was stuff lifted straight off mine. They were quite open about it, they said ‘all the arrangement stuff is fantastic but if you can’t get that sound we need to try it with somebody else’.

Phil Thornalley had been doing the Thompson Twins – I don’t know if that was the same time, but I think it was [it was earlier: Thornalley engineered the two previous Thompson Twins albums] – and he was just starting to work with The Cure then and was seen as a useful choice [that was also earlier – Thornalley had produced The Cure’s Pornography in 1982].

Q: Do you still have copies of your versions of the other two tracks?

I probably do. I need to dig them out. I’ve got an original test pressing with the original running order which I just saw today. I’d need to have a little poke around and see what I can find.

There was also… I don’t know if we ever finished it… I’m a bit hazy on my memory… we did two more tracks after the body of the album, and I think there’s a version of Let Her Go that I did and then there was one other track, I can’t remember the name.

We did two more tracks down at Sarm East and they were never released. I can’t remember what it was, it might’ve been the sort of thing where Since Yesterday had been a hit and there was a certain kind of acknowledgement that maybe it was right for me to be doing it or something – this is a guess rather than anything else – and we did do another two tracks and for whatever reason they weren’t released. I’ll try and find those. It might only be a backing track.

They were very very busy, the second the single came out they were very busy with interviews and stuff, I didn’t see much of them for ages after that.

Results, release and remixes

You know how it [Since Yesterday] became a hit do you? You know the process politically at Warners?

Q: No, not at all.

Well, I think it was released in late September or the beginning of October, but it was very slow to build.

Q: It hit the chart in late October.

And then the Christmas thing all swung into view but it was high enough up in November that Rob and Max thought it could come and go before Christmas. It was showing enough build in the charts that it could’ve had a longer life. Basically, I heard this story that Rob had had a look at what was potentially doing stuff for WEA that Christmas and Strawberry Switchblade were there and he said, ‘we’re going to keep this record alive come what may over Christmas and then hit it hard, because it’s the only thing for us in terms of new stuff that’s even bubbling around’.

So that’s why they did TV advertising, do you remember that? There was a short campaign in between Christmas and the new year which is why, as the Christmas sales came and went, it survived and came again in January.

All the pluggers and everything just dropped everything else and it caused a lot of frustration around the A&R department, because other people had things coming out and yet they said ‘we’re withdrawing support from everything else and this is the one we’re going to go for’.

And so all promotion and budget kept it alive for that period, and then ‘bang’ in the new year. [Since Yesterday had an uncommonly long period in the charts, 17 weeks, about twice as long as most records that only got to the mid top ten].

It’s impressive to see when they really decide to go for it, from a commercial point of view it was very impressive.

Q: Let Her Go comes out two months later, which is similar sounding enough to surely sell to the same people but different enough that it doesn’t sound like Since Yesterday Part Two, and it died, absolutely bombed. That makes sense now, hearing how Since Yesterday was pushed so hard.

Obviously I could argue it was because it was the wrong producer, but other people could argue it was other things! There you go, that’s ego!

Q: The 12 inch remixes. What were they all about then?

Well, I don’t remember doing one. I don’t know if I did, did I? Not to my knowledge!

Q: They all go uncredited except for the Let Her Go one, which didn’t actually come out on the Let Her Go single, it was on the Who Knows What Love Is? 12 inch.

It’s around that time there were all those 12 inch remixes, but I never really got the hang of that.

Q: So no-one knows who did these! Jill says she wasn’t even there for them.

Sounds like Balfe and Drummond.

Q: The Let Her Go remix is the only one that’s remotely listenable, and that credits Drummond and Youth – you can hear good creative musical minds working on it. But all the other ones are really dreadful, no musical merit except for the remnants of the original track. They don’t make it any different or better, just longer. ‘Not Guilty’ on your part, then.

Absolutely.

Q: Do you remember the David Bedford album that Strawberry Switchblade sang on, Rigel 9?

No I don’t.

Q: The contact was through the sessions you produced.

David Bedford’s done loads of stuff, he was involved with Tubular Bells and all that. I’d come across him cos I admired a piece he did, I think it’s called Twelve Hours of Sunset or something like that, and I really enjoyed it.

Q: So it was you who brought him in to work with Strawberry Switchblade?

Yeah, I said I think he’s the right person for this, and he did what I thought was a great arrangement, the orchestral stuff on Being Cold, and I think he did a little string thing on Another Day, just a string section thing that was pretty easy [also on Poor Hearts]. I also got Andrew Poppy in on 10 James Orr Street as well.

I used David Bedford for one little section on Orlando as well – you know, the movie [Motion did the score] – he did a section on that.

Q: After the album there was only one more single that came out in the UK, Jolene, which Clive Langer gets the production credit on.

Oh really?

Q: Do you find it odd that they went with someone else after you?

No. That’s a lesson that you learn over time. It’s not something that makes it any easier. I don’t feel bitter about it or anything, that’s just the way that the industry is. There was this feeling at WEA that my sound is too bright, there wasn’t enough bass, all that sort of stuff and they wanted something smoother. That’s what they thought, so they’d just go to the people who do that sort of stuff.

They were basically still obsessed about the idea that something could be a hit outside the UK, preferably in the States, and I think that drove a lot of their choice of producer. Obviously it’s disappointing, but I’m not sure I could’ve done a job on Jolene anyway, it’s not my cup of tea really.

Q: It smelt a bit of desperation, the previous single not having charted, so throw out a cover version. Drummond’s idea, apparently.

Ha! When in doubt, do a cover.

But it’s funny the kind of impact and the echoes that it has, it’s almost like a full cycle because I’d been listening to a lot of YMO [Yellow Magic Orchestra] before I worked with Strawberry Switchblade and I really liked that kind of techno thing, and I liked what Japanese music that I’d heard. It was great that it [Strawberry Switchblade] did so well in Japan – as a result of that over many years I’ve worked with quite a lot of Japanese artists. A lot of them have gone ‘oh, Strawberry Switchblade was really important to me’.

There’s one artist in particular that I work with, I think I was brought in because of the Strawberry Switchblade connection rather than she was influenced by it – the record companies are very powerful there – a woman called Chara, she’s monstrously big there. I’ve done stuff on eight albums with her, maybe two tracks on each album. A lot of it does have some of those kind of sounds, it’s just interesting that that’s why it should have connected.

I know in Japan they loved the whole image, that was an important thing as well. It’s kind of cute but they can see it’s slightly dangerous as well.

Q: When the album was finished was everybody happy with the result?

Off duty during the second visit to Japan, March 1986. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

I think so, yeah. I was very happy.

Q: Rose and Jill?

Yeah, they seemed very happy.

It was finished in summer, then it was released in September or October [the flagship single Since Yesterday was – the album wasn’t released until April 1985] and they were hoping to get the autumn rush as I was saying, and I didn’t really see much of them cos they were busy doing loads and loads of promotion. At the tail end of the recording of the album they were also doing a lot of stuff like photo shoots and general image things and beginning to do interviews. They worked very hard.

I remember I saw Rose some time later. It was all such a novelty to begin with, doing the interviews. And then after a while there were these rumours emerging, I think she said she liked mud wrestling or something like that in some interview. She said, ‘yeah, we say the same thing day in day out, after a while I got bored and started making stuff up,’ which is just brilliant. They were very much on a fast track for a while, preoccupied with the promotional side. I know that sounds very corporate, but that’s the way it is.

Q: They both say it exactly the same.

They were very good at hanging on to their integrity about what Strawberry Switchblade were, they were rock solid and they had a clarity and a presence which was great.

Q: How does the album sound to you now?

I just listened to it this morning, I thought it sounded fantastic. It still sounds very fresh, sounds very modern to me and I’m pleased with it. It had a lot of ideas, I think that’s the thing, it’s just packed. From my point of view I’m very happy with the way it sounds.

I’m not a big one for saying I’d do things differently cos I just wouldn’t, you know? It’s all part of a learning process. It sounds very assured to me, it sounds very clear and did exactly what we all wanted.

I don’t know how it could have been done better. There was this sense – they had high profile management in Balfe and Drummond, they were connected right at the very top in WEA so they got all the promotional machine. Other than taking issue with some of the choices of singles or whatever, the actual production side of things, I don’t know how it could have been bettered, really.

Q: Once they were on a major label it was likely to go like that.

How can you fight against such a commercial machine? The whole point is to sell records, that’s what everybody wanted to do, but then it’s at a cost. And that’s the thing – how do you hang on to your integrity while going through that machine? A lot of people describe those kind of record companies, particularly in the 80s, as being like machines.

Maybe it became a little more honest later in the 1980s where people basically wanted hits and it was kinds of cool to be pop. It may not be seen as cool now, but it definitely was, all the left of centre bands and people involved in the record industry earlier suddenly thought, actually it’s OK to go for a straight down the line commercial thing.

Q: The only way I could imagine it having gone differently is if they hadn’t signed with WEA but stayed with the indie thing. I’m surprised they didn’t put stuff out on Postcard. That was their mates and it was there.

If you look at Balfe and Drummond’s credentials, they were from a left of centre background, an indie thing, and then they wanted to make money and sell a lot of records. Even people at Postcard. I did an album with Win, formerly of the Fire Engines, and who Postcard was involved with. They all wanted to sell records. [Postcard offered a deal to the Fire Engines, but they opted for Edinburgh indie label Fast Product instead; after the Fire Engines split, two members formed Win]

It’s always a problem in indie music, how do you find an audience and build an audience and be self-sustaining? Either you have to choose these channels which do function and do work but then there’s the danger, as we’ve seen, that you can find the original motivation gets lost under the gloss.

Q: Selling records becomes more important than making good records.

But what’s a good record? Back in the 1980s a lot of it was sounding exciting, and from my point of view as a producer at the time I was very interested in what peoples drum sounds were like, stuff like that.

It’s just about developing a kind of character and an atmosphere and stuff like that, and having fun while you do it. I enjoyed it very much.

There is one other thing that I’m remembering, it was my girlfriend reminded me of this. It’s completely unrelated. I don’t know how I managed to swing this, but I made it one of the things with Warners about doing the album that I really wanted to try out a whole bunch of different studios and be in a different studio each week. This was because I was intrigued to know what they were like.

I’d worked in a number of studios but there were loads in London I wanted to try so we went into eight that I can remember but there are probably more. There was a week in Chipping Norton out in the countryside. I’m not a big fan of the countryside, but it was nice to be there. That one was towards the end.

The studio that we did the orchestral sessions in called Angel in Islington, it’s basically owned by a library company De Wolfe, but it’s a converted chapel and the main studio has got the old original organ and a view of the choir stalls at the back.

Built in to it is a fairly traditional late 1970s/early 1980s studio, wood all around and booths and stuff, and this organ and these pews emerging out of the studio. It’s almost like a movie set, when you come out of the studio to go to the loo you come out into the main church bit.

We were there late one night, probably about three quarters of the way through the album, and I was out in the main studio with Rose. I think it was a Saturday, maybe about ten or eleven o’clock at night, and she was showing me something, she was sitting down and I was standing up. Then all of a sudden there was this change in atmosphere in the studio. Things kind of went grey and it suddenly went really cold, and we looked at each other.

I mean, I’m very sceptical about all that paranormal stuff. So, there was this change in temperature and atmosphere, and I said to Rose, ‘did you just sort of sense something there?’, and she said yeah, and we compared. It was like something passing. I wouldn’t say a person or anything, but there was this strange presence that passed and it was really spooky. We asked the studio manager and he said people had experienced ghosts and stuff like that. It was an old church and there was obviously bones and stuff down there.

Q: Do you remember what track it was you were working on?

No. I think we relaxing, she was just showing me something on the guitar. She was out in the studio, just knocking around, and I went out to talk to her about something or other. It was Angel studios where we did the orchestral tracks, but we were working on most of the tracks most of the time form the word go, in bits and pieces. It was fairly close to the end, final overdubs and stuff like that.

Q: Just you and Rose, was Jill not there?

I think Jill was in the control room with Peter, I don’t remember who else was there. I just happened to be in the studio at that moment. I can’t remember if we were about to try something or just chatting. My only spooky experience ever.