Great Pop Music and Strawberry Switchblade’s Place In It

By strawberryswitchblade.net, 2003

The last Strawberry Switchblade photo session, just weeks before the split in June 1986. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

What makes great pop music great? Why do some songs hold us in their thrall all our lives? And why bother doing a website about the pop music of Strawberry Switchblade, a duo from years ago who only made one album? Answers to all these questions plus commendable hatred of prog rock are here.

Like Rose and Jill, the first music I was drawn to was punk. Back then in the late 1970s, pop music in Britain was dominated by the five forces of disco, prog rock, Adult-Oriented Rock (AOR), bubblegum pop, and punk.

Prog was the worst music ever made, the ultimate belief in style over content, where what mattered was technique and not soul. It said absolutely nothing and it said it loud and long. Very long. Being able to play 27 notes a second doesn’t mean a musician is good, any more than being a fast and accurate typist makes you a good writer.

Bubblegum pop has always been around, and while there are shining immortal nuggets in the collective consciousness, history does a thorough job of erasing the talentless majority of its proponents from our memories. Only obsessives can even remember Racey, Taylor Dayne, Glen Madeiros, Fabian and the legions of other soulless saps. It’s nothing to worry about, it’s just cack for people to hum along to in the hairdressers, music as wallpaper.

AOR was the beginning of Dad Rock; conservative and be-mulletted guitar music for people who’d grown up on loud guitars and so had a Pavlovian response to rawk n rawl sounds, but needed it in a safe, predictable, dull and sanitised form.

Disco did produce many powerful and magnificent records but it was aimed at an audience in, well, a disco. It was about free energy, kinetic good times. This is all well and good, but it doesn’t speak to people who are too awkward, self-conscious or insecure to Make You Feel Mighty Real. And for teenagers, almost all of whom are those awkward people, a fresh and honest music is needed to tell them they’re not alone, to give them something that understands and expresses what they feel, to give them something to truly belong to.

So for them, the only music was punk and its offspring of New Wave and indie. The scene that gave me The Jam and Buzzcocks, and later gave us Strawberry Switchblade.

1980s Cultural Rebellion

There in the early 1980s the dinosaur prog rock noodlers had died off, but there were new poser pretenders to take their place. Duran Duran would be in videos in flash suits riding yachts across tropical oceans. This was not music to affirm, enrich or inspire, it was entertainment to dazzle you into giving them acclaim and cash.

For the rebels, heavy metal was the most obvious option. People forget how absolutely huge pop-metal was in the 1980s. Def Leppard played stadium tours for fuck’s sake. But much of 80s corporate metal was just Stock Aitken and Waterman with a distortion pedal on the guitar. The meaning was the same, shallow egotists trying to take far more from you than they ever gave.

Jill: ‘That’s Kensington High Street tube station. I love that picture, look at the Our Price bags, from when people used to go out and buy records’. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

In many senses the true rebel music was found in the independent bands, people talking of real lives and trying to share, inspire and enchant rather than merely impress. Anyone who remembers The Smiths doing Shoplifters of the World Unite on Top Of The Pops will surely recognise indie as the most rousing, honest, real and therefore rebellious pop music of the time.

The 1980s was a time when great strides were made for individualism against all kinds of conformity, and Strawberry Switchblade were very much a part of it. Other 1980s values worked against them. Their commercial success was seen as something intrinsically shallow. Reading through the contemporaneous reviews (check out the Press section of the site) it’s incredible how 1980s market culture had embedded itself in the consensus. It was assumed that most people who had hits were somehow superficial, that they’d created music they didn’t actually like solely to foist it on a gullible public for profit and fame.

Women? From Glasgow? Yeah Right

Strawberry Switchblade weren’t taken as seriously as their contemporaries. Beyond the mercenary suspicions, there was also was a big dose of patriarchy in that. Had they been men, and had they been a larger band rather than a duo dismissed as mere ‘girl singers’, they would perhaps have been given their due. But the misogyn and London-centrism of the music industry tilted the table against them.

They were great feminists precisely because they didn’t make a big point of talking about feminist issues. They simply got on with being intelligent, well defined capable artists on their own terms, disregarding any pressure for dungareed social critique as comprehensively as patriarchal pressures. They were part of a new breed of bands, unashamed, fresh and honest.

The same Glasgow scene that gave us the Postcard record label and bands like Orange Juice, the Pastels, Primal Scream, the Jesus and Mary Chain and Aztec Camera gave us Strawberry Switchblade. For those who had the contradictory mix of self-consciousness and passion, of insecurity and fervour, then the awkward, delicate, fragile confusion and paradox of bittersweet happy-sad pop was there.

Pop Music That Matters

Pop music, on one level, is just something that is on in the background, something on the radio while we eat our breakfast. But it is this level that allows it to be around us and so let certain songs become part of our cultural fabric, part of our selves. Stuff that you (perhaps rightly) thought was insignificant froth when it was on the radio when you were 14 can now pull your heartstrings and move you emotionally in a way that the new, say, Radiohead, Eminem or Belle & Sebastian – no matter how great its creative worth – simply cannot.

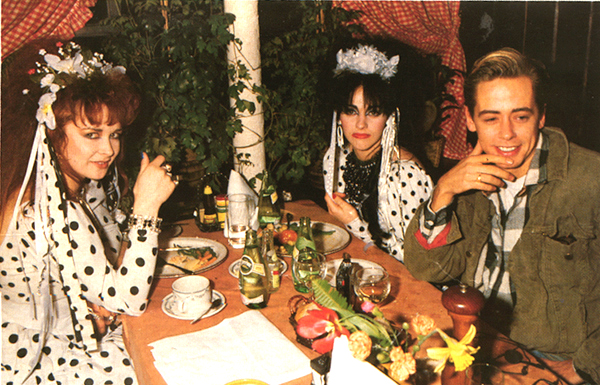

April 1985: For some, success in the music industry means filling a Rolls Royce with cocaine and throwing it out of the hotel window. For others, it means salad and mineral water with Nick Heyward. (Pic: Eugene Adabari)

Pop can do this – any music that has lived with you, in you, can do this. But pop’s shiny catchiness makes it commonplace. These songs are often widely known, and so anyone from your culture and generation – like it or not – will be bonded by a common canon of pop songs.

But there is something more too. The catchiness, the background-usage means that it is easy to get massively subversive messages out into mass consciousness in pop. My niece was five years old when she and her mates would all sing along to Afroman’s tale of excessive cannabis consumption Because I Got High. At the same age I was listening to Lou Reed telling me ‘but she never lost her head even when she was giving head’ in Walk On The Wild Side.

I remember the Housemartins’ bouncy guitar pop of Happy Hour – a stinging attack on unthinkingly selfish sexist wage-slave drinkers – being danced to by exactly the kind of people it criticised. Enough of us had listened to the lyrics for this kind of thing to be a hilarious Trojan horse.

It’s in this ability to simultaneously offer several different emotions and perspectives that real heart and soul can be found in pop music. And Strawberry Switchblade are a clear example of this. Delicate and fragile yet always powerfully individual, confused yet assertive. With Jill’s agoraphobia and the brutalities of Rose’s upbringing, both of them had a lot of anguish to express. And yet they wanted to do it with something beautiful and affirming that defied the pain they’d known.

Aldous Huxley said that, after silence, music comes closest to expressing the inexpressible. And it is an unnameable blend of emotions, at once happy and sad, cautious and wild, bold and timid, exuberant and mournful, that characterises the greatest pop music. It also describes Strawberry Switchblade perfectly.

For all the flaws and corporatisation of some of the released material and the half-finishedness of some of the later unreleased songs, there was something clearly real and true there, something in which we can still hear timeless truths and new possibilities, a little piece of genuine greatness created by Strawberry Switchblade.