Interviews by topic

All the exclusive, extensive interviews with the band and the people they worked with, intercut so as to deal with one subject or event at a time.

All the exclusive, extensive interviews with the band and the people they worked with, intercut so as to deal with one subject or event at a time.

Jill Bryson interviewed 9 June 2001

Rose McDowall interviewed 29 January 2002

David Motion (producer) interviewed 2 August 2002

Bill Drummond (manager/ A&R) interviewed 26 April 2003

David Balfe (manager) interviewed 19 May 2003

Robin Millar (producer) interviewed 16 February 2003

Tim Pope (video director) interviewed 22 June 2006

John Cook (bassist) interviewed 6 November 2024

Most of these interviews were conducted a very long time ago – bear in mind that those involved may express opinions they no longer hold.

General opinion, looking back

The photo session that yielded the Trees and Flowers cover picture, in Jill’s flat, 1983. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

Q: How long since you last did an interview?

Jill: So long I can’t remember. It must be at least 15 years.

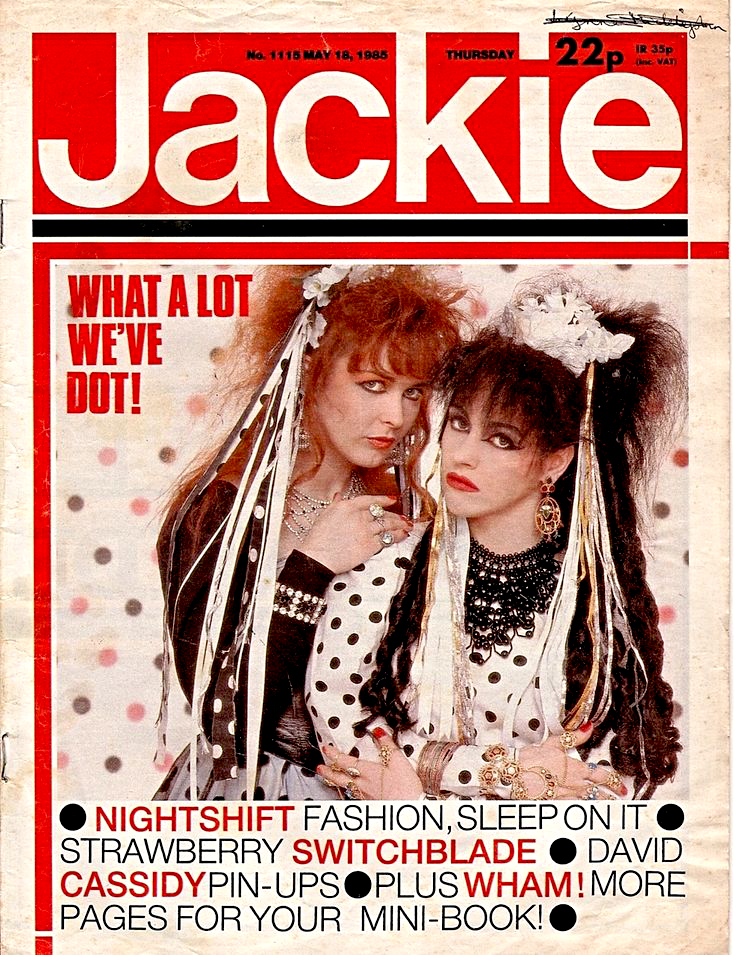

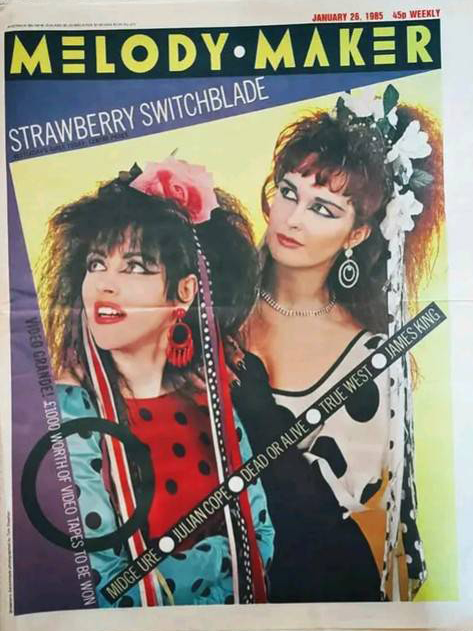

Q: Generally, how does it feel looking back at Strawberry Switchblade?

Rose: Brilliant. I think it was a totally fantastic exciting period of my life. We were just kids really. I mean, OK, we were twenty-something, but we were really just kids, and it just snowballed out of nothing, just wanting to form a band and have fun.

And suddenly we’d got John Peel sessions and we only had eight songs, and we had to finish the eighth for the session cos we had a Kid Jensen session as well. We were getting these gigs, and then we were to do an album and we still only had eight songs! It was fun and it was really exciting, to the point that we had no clue what was going on because things went so fast.

Jill: Yeah. It was a good thing to do. It wasn’t planned and it wasn’t expected, but it was a good thing to do. It was fun.

Q: Got the credit it that it deserved?

Jill: [considers] erm, yeah.

Q: Was it understood properly?

Jill: No, probably not.

Rose: Once things started to snowball it went really really quickly, which was also the demise of Strawberry Switchblade, because the more that’s going on the less control you have over what you’re doing, and the more other people are making decisions for you.

Inevitably it ends up being not what you started out for it to be, so I didn’t think it was worth continuing because it wasn’t fun any more. It was arguing with the record company about everything, and I thought ‘this was not what I wanted’.

Jill: Being with a major label and being female, they push you down one particular road. I don’t think they quite understood where we were coming from.

Q: What do you mean by ‘one particular road’?

Jill: They want to push you to be glamorous and they want you to be poppy and sell your stuff. I don’t mind pop music, I wanted it to be poppy, and it was the 1980s. I’m pleased with it. I think it was more the publicity machine behind the big record company that pushed us, there was a lot of fighting against that.

Q: Would it have lasted longer if you hadn’t had that kind of constriction?

Jill: It might have done, but I think it was difficult because me and Rose had quite a strange relationship, we weren’t really friends before the band started up. We were acquaintances and hung about in that particular group of people, and people would say why don’t you start a band, that’d be great, it’d be a laugh, it’d be funny; do something together, maybe because we were the only two girls in this gang of people and we liked similar sorts of music. So I didn’t really get to know her until we got together.

Q: Looking back now at the songs and the work, are you generally happy with it?

Jill: Yes. I loved it at the time and I still love it now. There are parts of it that I think are fantastic. I don’t listen to it that much, but at the time I loved it, really really happy with it.

Q: What are your favourites?

Jill: I love Being Cold. The guy who arranged the strings was appalled when I played the melodica over it, absolutely appalled. He was like, ‘you can’t do this, it’s not even in tune’, and I was, ‘that’s the way it is’, and I love that, I love the fact there’s a melodica over these lush strings, a huge string section. ‘No you can’t put that on’, ‘Yes I can, it’s my bloody record and I’m going to put it on! It’s our record and we’ll do what we like’. We’d decided we’d do that; you can’t completely erase everything quirky from it.

I like that, I like Deep Water and I like Go Away, I think that’s good. There’s not many that I don’t like on it, I was pleased with it. We really had a lot to do with it, if we didn’t like something we said, so stuff didn’t go on that we didn’t like.

Q: That’s true of most artists, though – nobody thinks ‘let’s go and make a bad record’, but many still do it. Is there nothing on there you don’t like?

Jill: A little bit, with the production and some of the, er, over-enthusiastic programming, I don’t really think it’s very us, I think sometimes it obscures the songs, but generally I quite like it. You’ve got to make a decision about some things sometime and generally I think it’s OK, I think it stands the test of time.

I like Trees and Flowers, I really like Sunday Morning, they have a kind of charm to them that the album doesn’t have. And I often listen to the [Radio 1] sessions. I quite like listening to them cos they’re much much more naive, there’s something quite nice about it.

Glasgow Punks: Rose and Jill before Strawberry Switchblade

Teenage punks at Glasgow Queen Street station, 1977: Rose, Drew McDowall, Jill and Margaret Broni. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

Q: What started you in music? What music did you grow up with?

Rose: The stuff I grew up with was a lot of 1960s stuff, like The Byrds, The Beatles, Tommy James and the Shondells, I really loved stuff like that. I was really into the Velvet Underground. I liked Roy Wood [giggles] from the 1970s. Not a lot I liked from the 1970s apart from punk, when punk set me free from my chains.

So I grew up with a lot of that [1960s stuff] cos my dad was really into music and he liked Johnny Cash and Buddy Holly and all that sort of stuff as well. Mamas and Papas, Simon and Garfunkel.

I had three sisters and they all liked different kinds of sixties music so I got to hear quite a wide range of stuff and picked out the things I liked the best, which tended to have lots of harmonies which were a bit psychedelic or the Velvet Underground – Lou Reed was just a total genius songwriter. He is god!

Q: Were you close to Jill before the band?

Rose: Oh yeah, Jill and I were really good friends, and we were pretty notorious around Glasgow for going around all dressed up. Not really so much in the early days, but when I was in The Poems I used to be overdressed, outrageously dressed all the time.

Q: A lot of people forget what that meant then. Nowadays you can work in offices with multi-coloured hair and eyebrow piercings, people forget what it was like up until the 1980s.

Rose: It was, like, dangerous! It was actually dangerous, we got beat up sometimes and stuff like that. Bikers beat me, my best friend, my boyfriend and her boyfriend up pretty severely. We all ended up in hospital just because we were punks and we were quite outrageously dressed.

Some guy wanted to dance with me and tried to pull me off in a corner, I pushed him out the way, and he went off and told all his biker friends. I was five foot nothing and wearing flat shoes and these great big bikers come up. One had my boyfriend and put him against the wall and he was going to put a glass in his face, and I jumped on his back and was hanging on to his shoulders to try and pull him away, and another biker punched me on the nose and I was out for the count. Then I woke up and bouncers came and threw us out.

Q: It’s a really weird thing, that rigidity of fashion at that time, how scared people were of anything that was different. It was something the 1980s really broke down and gave individualism the chance to come through. It’s got to be emphasised that almost everyone was not a punk on the late 1970s, and those who were ran real risks.

Rose: Exactly. And especially in a place like Glasgow which can be a bit violent anyway. I suppose if you were in a little village you’d probably get talked about and whispered about but probably not beaten up so much.

But if you’re in a big city like Glasgow you have to watch where you go. There were certain pubs you wouldn’t even dare walk into. I couldn’t really go into pubs anyway cos I was always thrown out cos they didn’t believe I was old enough. Being thrown out of pubs when I was 27, that was quite funny!

But it was a really big deal being a punk then.

Q: Jill said you had to go out to Paisley to find somewhere where someone would play the records.

Rose: That’s right, yeah.

Q: A city the size of Glasgow and nowhere would play the records, it was that much of an outsider thing.

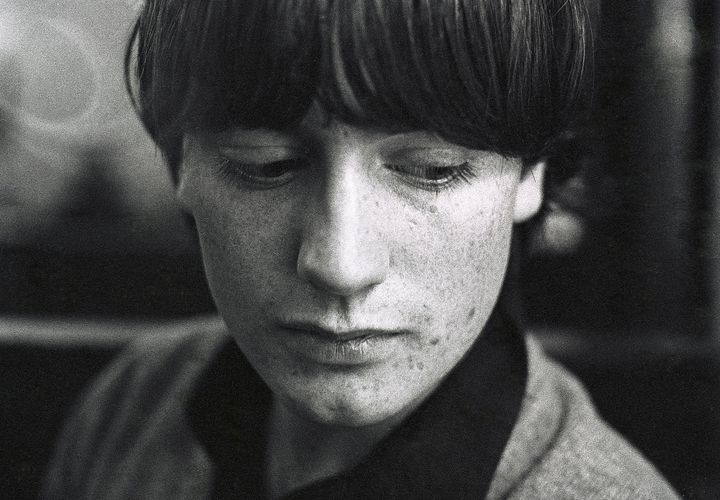

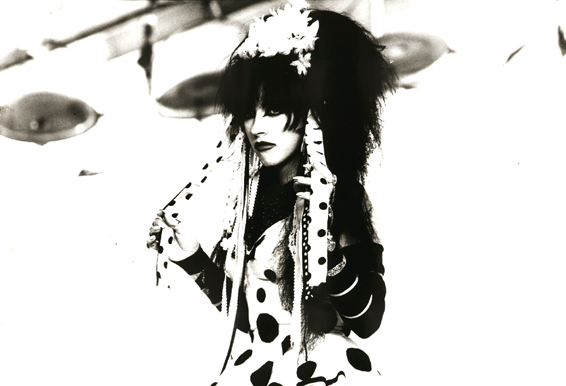

Rose, photo session for The Poems, 1980 or 1981. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.rmission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

Rose: Right at the very beginning there was a couple of little clubs. There was one on Buchanan Street – there’s a big centre built there now – and the DJ had two albums, one was the Damned and I think one was the Stranglers, and a few singles and he just played them over and over again all night. But that closed down because nobody wanted to put punk things on, it was an affront to society.

When punk happened it totally saved my life. I was a really fucked up teenager who really did not want to conform to the norm, never had even when I was a kid. I didn’t want to be like everybody else because I didn’t respect them. But I was at that age where I felt ‘what am I supposed to do?’, and then punk happened. ‘That’s what I’m supposed to do! I’m supposed to be me!’

Punk allowed me to be me without feeling like a fake. It totally liberated me. I didn’t have to be a girly girl and it wasn’t expected of me, or if it was it didn’t matter. I would probably have done the same thing anyway but been really outcast or locked up for being a nut. My mum was always telling me I was a bit crazy. Punk really was my saviour. It sounds like an extreme thing to say, but for a pubescent teenage girl who’s totally fucked up about life, it was really really really my saviour.

Q: You came out of art school didn’t you?

Jill: Yeah.

Q: What were you doing there?

Jill: Fine art, mixed media. Which meant just doing a bit of everything. I did a lot of photography and film, painting.

Q: What did Rose come out of?

Jill: Just the punk scene. She got married very young and she had a child at, I think, about nineteen. Her child was quite young when we started, only about a year or two old.

Q: You say a teacher didn’t have much time, but having a year old kid?!

Jill: Yeah exactly, it’s quite amazing. But I think her husband wasn’t working at that time so he could look after her as well, and she had quite a big family and they looked after her, so it was OK.

Q: How did you and Rose meet? How long did you know her before the band started?

Jill: Not that long. I met her through the punk scene in Glasgow which was tiny at the time, around 1977. There were so few, you knew everybody who was a punk. It was the first thing I’d ever been involved with, I was 16. But I didn’t know Rose well, I just saw her around and knew her, she was quite a character.

Q: There has been this revisionist history that everyone in 1977 between 15 and 20 years old was a punk. It’s a comparable lie to the one that says that everyone of that age group in the mid-late 60s was doing loads of drugs.

Jill: Yeah, it’s a complete myth. It did expand quite quickly after, but by that time we weren’t really interested in punk anymore.

Q: This is ages before the band isn’t it? We’re talking 1977 and your first record was 1983.

Punk times, c.1977. Jill: ‘I think we were in Satellite City which was above the Apollo in Glasgow, seeing the Simple Minds, it might have been while they were still called Johnny and the Self Abusers. That’s me at the front, Marge on the right, then her friend Ricky, we were all at school together. I don’t know who the guy laughing is, I can’t really see. Then Colin McNeil who was the bass player in the Backstabbers and James King and the Lone Wolves, he was at school with us as well. Then it’s Shirley, then Karen Donnelly at the very far end. She ended up gong to London and hanging out with Adam Ant and his crew’. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

Jill: The punk time was before Rose got married and had a baby. I saw her then, I didn’t really know her, but I knew of her. Basically, there was a coachload of people into punk in Glasgow. Punk was banned in Glasgow, you couldn’t hear it anywhere.

We used to all meet outside this record shop in Union Street in Glasgow with people looking at us disgusted. We’d all get on this coach to go to a club in Paisley outside Glasgow where – I think it was every week – they just played punk records and you could go and dance.

And occasionally they’d have bands. Generation X played there, and a lot of the Glasgow bands. I didn’t go that often because at that time I was recovering from agoraphobia. I’d been agoraphobic for a year and missed a year of school. I was 16 and I’d left school and started going to college.

I tentatively tried to go [to the club], I didn’t often go, it was a bit far for me. It shows you how much I wanted to go that I actually did it, I wanted to go out so much and hear this music.

Q: It’s incredible that you had to go outside the city to find somewhere to hear this music.

Jill: You could hear records you liked and meet people who liked the same kind of music you did. It was so rare to find anybody into it. You could spot them a mile off! You kind of knew everybody, and there was a couple of record shops that we used to go and hang about in, we were that desperate.

Most of us were quite young, around 16, 17, so we couldn’t get into pubs. But we used to get into the Silver Thread Hotel in Paisley, near the Coates thread factory. It was the most unlikely place you could possibly imagine.

Q: Was it the punk thing that made you start playing guitar?

Jill: Yeah. Before that I would’ve thought you’d really have had to play it, be able to play solos and rock guitar and, shit, I’m not going to do that am I? Women didn’t really form bands did they? At that time I really liked Patti Smith. I’d got Horses when it came out, it was incredible. It was before punk, wasn’t it?

Q: 1975.

Jill: Yeah, I was 15 and had agoraphobia. I’d heard it on the radio and got a friend to go out and get it for me. It was just amazing. I wanted to be her, I wanted to look like her. I knew there was no way I could ever look, you know, wasted. I was always going to look, well, healthy.

I thought Patti Smith was fantastic but she looked like a boy and her band were men. But then when punk started there was X Ray Spex and Siouxsie, and The Adverts had a girl bass player, just loads and loads of women started appearing in bands like The Slits.

I thought it was great. It was about enthusiasm and not about ability, it was about ideas. And also I thought, well, if I just hammer something out and have the confidence to get up and scream into a microphone I could do it. At the time I was a bit too young, I didn’t have a guitar or anything, didn’t know anybody else who was in a band. After that there were two or three punk bands in Glasgow and I remember singing with some of them in rehearsals and stuff.

Starting to write music

This shot was used for the back cover shot of The Poems’ single Achieving Unity, 1981. The front cover was simply a polka dotted square. Left-right: Drew, Rose, Ian. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

Q: When did you start writing yourself?

Rose: There was a big concert in Glasgow at the Apollo Theatre, which doesn’t exist any more, I think it was a Stiff tour or something. There was loads of different bands playing, and the Ramones were playing. I was there with my boyfriend at the time and we just looked at each other and thought ‘if they can do it we can do it!’.

They were really trashy but really really good cos they had a real pop sensibility, and I just love melody. So we formed a band and he was the singer, I was the drummer, and we had a guitarist and someone else who would occasionally play violin.

Q: Is that The Poems?

Rose: The Poems, yeah. We released a single and we recorded an album, we even mastered the album, but before the pressing the master went missing.

Q: Are there any copies anywhere?

Rose: I must have a cassette copy somewhere, but I’ve got sooo many cassettes. I’m going to go through them all and see if there’s anything salvageable on that cos it would be interesting for me to listen to it again. The music was quite interesting, the instruments we used were quite interesting, so I’d quite like to hear what it sounded like now.

Q: When did The Poems get together?

Rose: The Poems got together in ’79, I think. My first daughter was born in ’79 and I played a gig when I was pregnant, so it must’ve been ’78 or ’79. Strawberry Switchblade got together in 80…I don’t remember awfully well!

Strawberry Switchblade and The Poems did gigs together, cos I used to organise a lot of the gigs in those days.

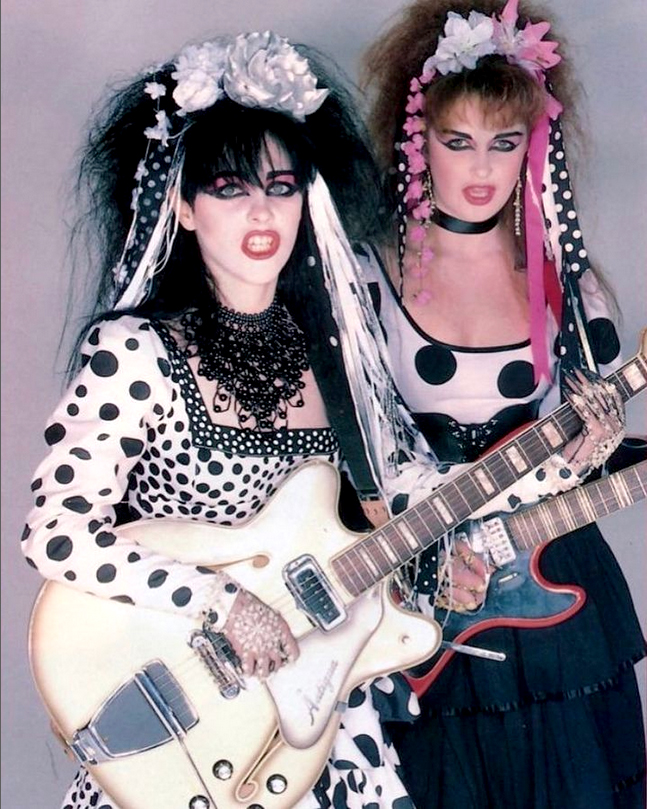

Q: So you’d be playing in both bands?

Rose: Aye, and I’d get paid twice so it was quite good! And a quick change of outfits from The Poems to Strawberry Switchblade, which weren’t really that different anyway; black lace frilly things for The Poems and then polka dots for Switchblade.

That was good fun, but then The Poems fell apart basically cos Switchblade got busy.

Q: So when did Strawberry Switchblade get formed? How come one band wasn’t enough for you?

Rose: I was sitting on a bus with James Kirk from Orange Juice. He was coming out to my house and he’d done this fanzine called Strawberry Switchblade. He said he wasn’t going to continue doing the fanzine, I said that’s a fantastic name, it can’t just die, and he said ‘have it’. I went ‘really?’ and he said yes, have it. So I went, that’s it, and basically I had the name Strawberry Switchblade so I had to form a band cos it was such a good name!

Q: There’s so much in this story that’s the other way around from normal – having a Peel session without sending in a demo, having sessions booked without having the songs, having a name but no band.

Rose: I know! And then I said to Jill ‘I’m going to form a band’ and she says ‘can I be in it?’, I said, ‘yeah, what do you want to do?’. She said ‘sing’, I said, ‘nah, I’m going to sing’

Q: You’d been playing drums with The Poems hadn’t you?

Rose: I’d been playing drums, yeah. So I bought myself a 12 string guitar and taught myself to play a few chords – which is all you need to do to write a song – and Jill bought a guitar. So she was going to be the guitarist and I was going to be the singer. I’d do rhythm guitar and she’d do frilly bits.

Q: How did the band actually get started?

Alan Horne, head honcho of Postcard Records, interviews Viv Albertine of the Slits for the never-completed fanzine called Strawberry Switchblade, while Jill Bryson looks on. Glasgow City Hall, September 1979. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

Jill: I suppose we started getting together at Rose’s house. I bought a guitar with the little money that I had.

Q: Had you been playing guitar before that?

Jill: No! My sister had a classical acoustic guitar that she knew a few chords with, and she had a ‘learn to play guitar’ book, Burt Weedon or something like that. A classical guitar’s got such a wide neck and I thought, ‘never!’, the action was so high you were like [straining face] even to play G.

So I saved up and bought this semi-acoustic, it was the heaviest semi-acoustic guitar I ever picked up. But it was great cos I could play it, it had a proper neck and a decent action.

So I learned a few chords – literally about three – and thought, well we can do it, I know three chords. And we thought we should have something else; I think Rose knew the bass player, the teacher, and I knew the girl from the Student Union and her brother was in a band and he had drums so that was how it had to be. She’d obviously practised on his drums, maybe he’d shown her a few things. We were all really limited in abilities, you could say.

Q: Did you play any instruments in any bands prior to Strawberry Switchblade?

Jill: No, just did some shouting into the microphone and that was about it. It was good fun. Rose and her husband had a band, she played drums. Quite badly, I have to say, but that was fine, in the punk tradition, you know? She just hit them. I remember going over to see them. They were called The Poems. I remember going to see them when she was about 8 months pregnant; she’s out here and she’s not very tall so she looked huge. That was quite something.

Q: When did you start writing? Were you writing before Strawberry Switchblade started?

Jill: No.

Q: So you decided to start a band and then started writing songs?

Jill: I was at art school when we started to do it, so I was a bit older. I had a flat round the corner from Alan Horne, the guy who ran Postcard Records in Glasgow. They were just a real strange bunch of people who shared a flat. They were just great. They shared a flat, a very neat flat with a Polish girl called Krysia Klasicki who was an artist, and this guy called Brian Superstar who ended up being in The Pastels.

It was such a weird, strange, great place to go. And then Edwyn who was the singer in Orange Juice lived round the corner, and David McClymont who was the bass player lived up the road. The drummer in that group worked at the dole office.

Jill, wearing Rose’s face: ‘That’s me outside my mum and dad’s house in Glasgow, that’s probably quite early as well about 1980 and I’m wearing a Poems T-shirt, which was Rose’s band with her husband.’

We all tried very hard not to work so we could rehearse – they all did, I was at art school – but nobody wanted a job in the holidays when they were at college, so him and Edwyn I think, both of them, got grabbed and made to work in the dole office. We’d go down to sign on and they’d be behind the counter going ‘you bastards!’, a really resentful look on their faces.

We used to go through to Edinburgh a lot, I remember having to sit in the station all night when we’d missed the train back. A lot of bands would play Edinburgh but they wouldn’t play Glasgow for some reason. I think there were smaller venues in Edinburgh, so people like Siouxsie & The Banshees would play there rather than Glasgow.

Knowing Orange Juice and that lot, because I lived nearby, they were just like, ‘oh yeah, you should be in a band, you should do this, you can do demos with us’. It was actually the guitarist in Orange Juice that came up with the name Strawberry Switchblade. I think it was going to be the name of a fanzine or something, which he’d got from a psychedelic band called the Strawberry Alarm Clock, and it was just his punk version.

At that point the guy I was going out with, Peter, he was a photographer, him and Stephen from the Pastels and Edwyn and Alan Horne and all those kind of people, they used to do fanzines all the time. I remember one fantastic article that Peter wrote called How To Fail At Job Interviews! So classic, such a stupid punk thing, such a dropout thing. One of the things was have a really filthy old snotty hanky and pull it out, wipe your nose a lot. The first question you have to ask is ‘how much money do I get?’!

There were all these different fanzines. One was called Juniper Beri Beri [see Press section for Strawberry Switchblade feature in issue 1 of JBB]. Strawberry Switchblade, I don’t think they ever printed any of it. They were just interviews with people. I remember going with Edwyn to interview The Slits. I wasn’t that keen on them, they had this attitude, ‘hey we’re real London trendies and you’re just hicks from the sticks’. They kind of tolerated us.

Sorry, this is unstructured rabbiting.

Q: No, this is great! It’s not something you normally hear of, punk and indie roots for a poppy band on a major label, this is a really good scene-setting thing.

Strawberry Switchblade early days

First ever Strawberry Switchblade gig, Spaghetti Factory, Glasgow, December 1981. Carole McGowan (drums), Janice Goodlett (bass), Rose McDowall (vocals), Jill Bryson (guitar). Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

Q: Weren’t there four of you to begin with?

Jill: There was four of us to begin with. We wanted to be a girl group and rehearse as a group and play as a group. The first few gigs we did in Glasgow were as a four piece. But one of the girls was a teacher and she didn’t have much time, and the other one was studying to be a marine biologist, so I don’t think it [the band] was high on their list of priorities.

Q: Who were the other two?

Rose: The other two were Janice [Goodlett] who played the bass and Carole [McGowan] who was a drummer, her brother taught her to play drums. She had two rhythms she could play, one was for the slow songs and one was for the fast songs. Which was OK, cos if you’ve only got eight songs it means you don’t have time to get bored!

Q: Where did you know the other three from?

Rose: Jill I met through her boyfriend, I used to hang about with him before she went out with him. The bass player I got through meeting her in clubs and stuff, I didn’t know her that well. And Jill knew the drummer a little bit, so we got together that way. We didn’t know them that much when we came together but we thought we’d try it out anyway.

Q: Did you know straight away that you were really going to try to make a go of it with the band, or was it just arsing around in rehearsals?

Jill: Well, it was funny, people were encouraging going ‘yeah yeah, you can support us and support the Pastels’ and at that time there were a lot more smaller places to play and there were a lot more groups who needed somewhere to play.

Q: So we’re talking, what, 1982?

Jill: Earlier than that, I think it’d be about 1980, that sort of time. Me and Rose thought we’d get a band together. The drummer was someone who ran one of the Student Unions. You weren’t allowed to get into the Glasgow University Men’s Union, but there was a Women’s Union, the Queen Margaret Union.

Q: What? Did they have men-only gigs and stuff?

Jill: ‘That’s the first picture of Strawberry Switchblade. Right to left that’s Janice the bass player, Rose, Carole McGowan who played drums, and me. It was very cold. That’s up near the Botanic Gardens in Glasgow.’ Around November 1981. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

Jill: Well, at the women’s union men could get in, and it was run by this girl Carole McGowan who was our drummer and she used to let us in. You weren’t supposed to get in if you weren’t a student, but she just let anybody in. She used to book the gigs and everything.

They put on a lot of local bands and they also had discos, we used to go and wait till they finished playing Hi Ho Silver Lining and then we’d all get up when they played their one punk record, fling ourselves around and then get off again. They would intersperse punk records throughout the night, but there was that little to do in Glasgow you would put up with it, you know?

Q: Hi Ho Silver Lining in 1980?

Jill: It might have been a bit earlier

Q: What was anyone doing with that record after 1975?

Jill: It was alive and well in student unions, probably all round the country, not just Glasgow. We’d have to get suitably, like, [disdainful face with theatrical sigh] for those songs. You know, Freebird by Lynard Skynard. It was really funny, it was just so rigid then, whereas now….

Q: Whatever you’re into there’s somewhere to go.

Jill: Exactly. People are a bit more tolerant now. They used to throw things at you if you were a punk in Glasgow. They were so intolerant, you took your life in your hands, especially if you were a guy. If you were a girl it was just insults. Several of my friends were chased through town and punks had the living daylights thumped out of them.

Q: People don’t realise how marginalised punk was. There wasn’t independent music properly yet, punk invented it. Fashion was a very rigid thing, which is something the 80s broke down completely.

Jill: Absolutely.

Q: How quickly did it develop?

Jill: Really quickly. We got together, wrote a couple of songs then booked a gig! We had to write enough songs to do this gig in The Spaghetti Factory in Glasgow.

Q: What kind of venue was that?

Rose and Jill at the first Strawberry Switchblade gig, Spaghetti Factory, Glasgow, December 1981. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

Jill: It was actually just a restaurant called the Spaghetti Factory. You can imagine what it was like, a pizza place in the West End. They had a little stage at one end and they had people play there, but not usually bands, I think it was more usually piano and stuff.

Q: You go out for a pizza and what you really want is an inept indie band at the end of the room!

Jill: A really really bizarrely dressed up inept indie band. It was in December this gig and we managed to write six songs, which was quite something.

Q: Which year would that have been then?

Jill: It might have been 1981 I suppose. 1981 or ’82. [It was definitely 1981]

Q: How do you know it was December?

Jill: Because it was snowing and nobody could come, the buses were off!

Q: And you did it anyway?

Jill: Yeah! And there really was hardly anybody there. And I remember that, cos it was in the West End where we lived, Alan Horne came and Edwyn and basically they were the only people! It was so funny. And Peter took some photos of us standing there looking like Christmas trees.

Q: Were the band any good at this time?

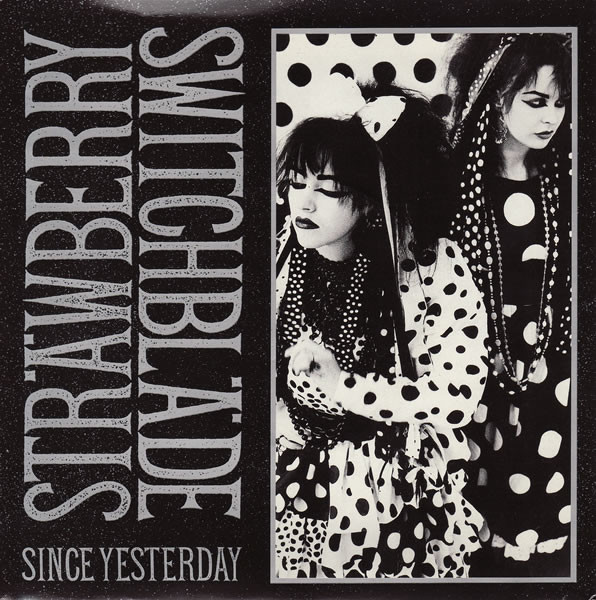

Jill: I don’t know. People liked us, but I think it’s just because we were women and we did little short pop songs. It was the same songs, Since Yesterday and stuff.

Q: So the very first stuff you were writing was the stuff that ended up on the album?

Jill: Yes. Most of them. They went through change as we progressed and learned an extra chord. The lyrics got a bit more refined. Some of them changed even at the stage when we were doing the album, and we had a producer saying ‘work on that bit there’. But to begin with it was still those songs.

Q: You’ve just picked up a guitar and you’ve just started to write songs and it’s those songs!

Jill: It was literally, ‘we’ve got to write some songs! How many have we got now?’. We started doing a few little gigs around Glasgow which kind of pushed us each time cos we’d have to rehearse for them. I remember sitting at home, at my parents, sitting in the back room till god knows what time just strumming, trying to come up with something. I’d come up with a tune and sing the melody to Rose, she’d have to write the lyrics, then we’d sing it to the band and they’d play along.

Q: Is that generally how they were written? Everything’s credited equally to the two of you.

Jill: Yeah.

Writing the songs

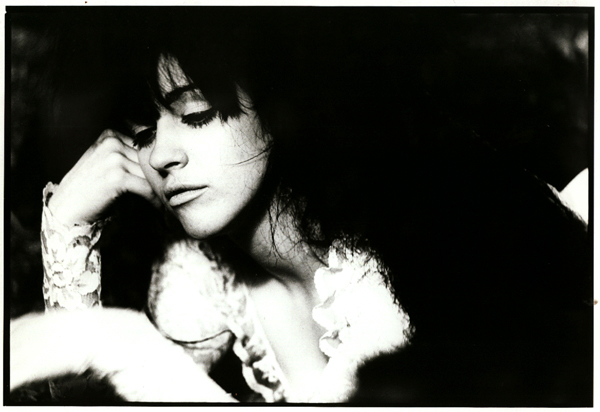

Rose & Jill, at Jill & Peter’s flat, West End Park Street, Glasgow. Probably 1981 or 1982. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

Q: How did you write the songs? You were already writing with The Poems.

Rose: It was mostly vocal stuff I was writing with The Poems, I wasn’t really playing any instruments except the drums. I taught myself to play twelve-string guitar. Basically either Jill would come up with a guitar line and I would put a vocal melody on it and the words, or I’d come up with both and occasionally she’d come up with both.

The majority of the time it was… well, it’s difficult because if you actually looked at the whole thing, the whole album, I probably tended to write most of it as a whole, but Jill wrote quite a lot of the music. She’d write one song, I’d write another song, but when I did it I tended to write the vocal melody and the lyrics as well, with a couple of exceptions. We used to write like that and then come together with an idea.

Working with Jill was great, it was really really good because our personalities together were perfect for writing songs. She’d do something that would really excite me and I’d do something that would really excite her. The enthusiasm that came off each other was completely electric, it was so exciting and so much fun. And all we ever did was laugh. We were just really happy and we worked together really really well. I haven’t ever worked with anybody like that since then.

I kind of miss that, I miss our working relationship. It was really good for most of the time, it’s just that there became stresses towards the end. It was actually really good fun when we were sitting down and one of us would come up with an idea. We were good for each other, I think.

We were good for each other’s confidence – we were learning guitar as we wrote the songs, ‘I’ve learnt this new chord’, ‘Oh that’s really nice, let’s see if we can fit it in with the other ones we know’. It was like everything drew out of the same pot. We worked well together, we worked really well together.

Q: Although it was really collaborative, you were writing the lyrics on your own. Did you ever do much explaining of what they were about? In a format like the three minute song there’s bound to be so much left unsaid, but yours tend to be really uncontextualised. It feels like being dropped into the middle of a situation, like a snapshot of a relationship where although there’s clearly history and consequences, the lyrics have just picked a moment and described the feeling and feelings of that moment. Did you ever explain to Jill where the lyrics had come from and what they were describing?

Rose: A lot of the lyrics were just straight out of my life, basically. It was a memory and I’d just put it into words like a poem. Little parts of my life that were stuck in my head, I’d write songs about them. Things like Little River, the reason I wrote that song is because it was one of my favourite story books in school when I was a little girl.

Things like Go Away, my cousin had taken me out into the countryside and he used to play really nasty tricks on me. He’d take me for great big long walks – cos he lived in the country and I’d go and visit them – and then he’d dump me somewhere. He’d tell me to sit on this wishing stone, close my eyes and count to ten and make a wish. I’d close my eyes, count to ten, make a wish and open my eyes and he’d be nowhere to be seen, and I would have no idea where I was. That stuck in my head, and that was what Go Away was about, basically.

Q: And yet there’s a couple of references in interviews to the fact that lyrics were never written together. I think you said you wrote By The Sea together and that’s about it. Who did what in the songwriting?

Jill: When we started off I used to just do the melodies and write the music and she did the lyrics. I wrote Trees and Flowers on my own. Sometimes if I was playing I’d come up with something [lyric-wise] to fill it in, to help with the melody and the flow, and we’d just stick with it. And if I liked it I’d go ‘I’ve got some words’. And as we went on Rose decided she would learn to play guitar as well – if I could do it in three months she could! Then she started to write her own music as well.

Q: So did it get more collaborative or did it make you develop ideas separately?

Jill: It did get more that one of us would come in with a finished thing. To begin with I came in with the tune and the melody and she’d tape it and go off and write the lyrics, but as soon as she learned to play a few chords she did her own stuff. But then we’d kind of get together to rehearse it, thrash it out a bit.

Q: Is there any stuff you wrote the lyrics for apart from Trees and Flowers?

Strawberry Switchblade as a 4-piece band, 1982. Left to right: Carole McGowan (drums), Rose McDowall (vocals, guitar), Janice Goodlett (bass), Jill Bryson (guitar, vocals). Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

Jill: Being Cold, and Who Knows What Love Is? which is totally terrible and was supposed to be kind of, er, ironic. But it didn’t really work out that way.

Q: But set it to music and it just floats, it’s gorgeous.

Jill: I did that one, and the words and music for Being Cold and Trees and Flowers. I think that’s the only ones I wrote words for, because I’m not really a lyrics person.

Q: Did you decide right at the beginning that everything would get credited to the two of you?

Jill: Yes. Well I just thought we were signed as a duo and we just decided to credit it to the both of us.

Q: With writing the lyrics, was there much explaining the meanings to each other?

Jill: No, nothing. None.

Q: So Rose turned up and said ‘here’s the lyrics’ you just did it? Were you not curious about what she was writing about, and were you not wanting to explain your lyrics?

Jill: I used to ask sometimes but she never did explain. I never really asked.

Q: Lots of them are like snapshots, taking a segment of a situation between two people and the obvious thing is to ask ‘where did that come from, what did it come out of?’

Jill: I think it comes out of not thinking too much cos you have to kind of come up with it now, you know, and so it often wasn’t thought about to much. She was never very forthcoming about what any of the things were about.

Q: There’s such a good marriage of the mood and descriptiveness of the lyrics with the melodies, so many of the songs are really of-a-piece, it’s really odd they’re coming out of separate minds that aren’t explaining to each other.

Jill: Absolutely. I think it’s that kind of instinctive thing, it’s not thought of. Sometimes it’s better if you just do that. After we’d done that album it was most of the songs we’d come up with – we weeded a few out and obviously we refined them a bit – but basically it was those songs. And once we got ‘oh it’s serious isn’t it? It’s like a job, we’ve got to do this’, it kind of took the edge off it.

Q: There’s an extra pressure and weight when you know you’ve got to do something and you know where it’s going to go.

Jill: Yeah, and it was awful, that’s not really what it was about, it had been a really instinctive spur of the moment thing and that’s why it worked. Cos it wasn’t high art or anything, it was pop music.

Q: Well yeah, it is ‘just pop music’ and you can just hear it on the radio as you go past and you don’t have to give it your full attention to get something from it, but the great thing about pop music is that you can go as deep as you want with the good stuff, it can communicate and move you on a level as deep as any other art form, especially when it’s the performer’s own work. You can’t do that with Hear’Say but you can do that with, say, T. Rex, and certainly with Strawberry Switchblade.

Jill: Yeah, yeah I know. It’s interesting to find out what people are about when they’re writing stuff. If they’re not writing stuff then it’s just a case of performing it and do you like the performance of it or not.

Q: Which of your contemporaries did you like and feel part of a scene with? It was a really great time for bittersweet melancholy indie music being huge with the likes of The Smiths coming through and Soft Cell just gone. Which of it were you listening to at the time?

Jill: ‘That’s me with Edwyn Collins from Orange Juice and Alan Horne of Postcard Records. That’s early, that’s probably 1981, before the band. That’s outside Postcard Records, I lived round the corner.’ Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

Jill: The Smiths. And Orange Juice, we knew them and I liked them. I didn’t like their recorded stuff, but I liked the weird jangly stuff, I’ve got loads of demos of theirs that are fantastic but, again, when the record company got hold of them they kind of sanitised them. They tried to make Edwyn into a soul singer which he clearly isn’t! I mean, he’s got a great voice, but it’s weird, it’s not Al Green. I remember wondering ‘why are they doing [Al Green classic] L.O.V.E. Love? Who put that in their heads?’.

I was listening to Aztec Camera. I listened to John Peel a lot, all the stuff on John Peel. I liked a lot of the Glasgow bands, we’d spent a lot of time going around to see them. I really liked the Pastels, I thought they were just fantastic, that real spirit of punk bizarre mixture of people, just great. Always good going to see them; they were hit and miss but I always thought that was great.

Q: They’re still really acclaimed now, their name crops up a lot in indie zines.Jill: I really rate them. Bry Superstar the guitarist, he looked like he worked in bank and he actually did work in a bank, but he was really….he didn’t have a bank mentality! I don’t know how he did it. The Smiths were always on, always playing.

Q: It’s difficult to overstate the importance of the Smiths in music at that time. Every album track, every single, every B-side of their was great, no other band had done that. And at such a rate – an album a year plus a few singles not on the album, all with new tracks on the B-side too.

Jill: The Smiths are one of the bands I can remember seeing on Top of The Pops really really well. But yeah, all that kind of indie guitar bands. I recently found loads of tapes a friend made just after that point and they’d put a lot of electronic stuff and Janet Jackson type stuff and I can’t actually listen to it. I remember thinking at the time it was quite funny, but I just can’t listen to it now.

Q: It was a music press inspired thing to pretend to be into soul music more than you were, and so to take any contemporary Black artist and try to pretend they were as good as Marvin Gaye.

Jill: It makes bad listening now. I put a tape on and thought ‘this might take me back’. It did, but it wasn’t good.

[Change of tape – comes back in on…]

Q: It was like this when I talked to Jill, four hours of tape!

Rose: We’re a pair of gabs, I tell you!

Q: Totally! It’s uncanny, it’s so obvious that you worked together. And when you were talking about writing the songs, you used almost identical words to hers about the process.

Rose: Really?

Q: Yeah, really emphasising how much of a laugh you had doing it.

Rose: Yeah, and bouncing enthusiasm off each other was just great.

Q: And, as with her, I’ve got a list of questions but I just need to look at it once in a while and cross off the ones you’ve answered in the course of just talking.

Rose: It was great, we used to get together and think, ‘the theme is red and black today’ and throw everything that we possessed on the floor – beads, jewellery, earrings, everything that was red and black – put it all on then go out, jangling everywhere we went! People would hear us coming from half an hour before we got there!

Development: exit the rhythm section, getting a manager

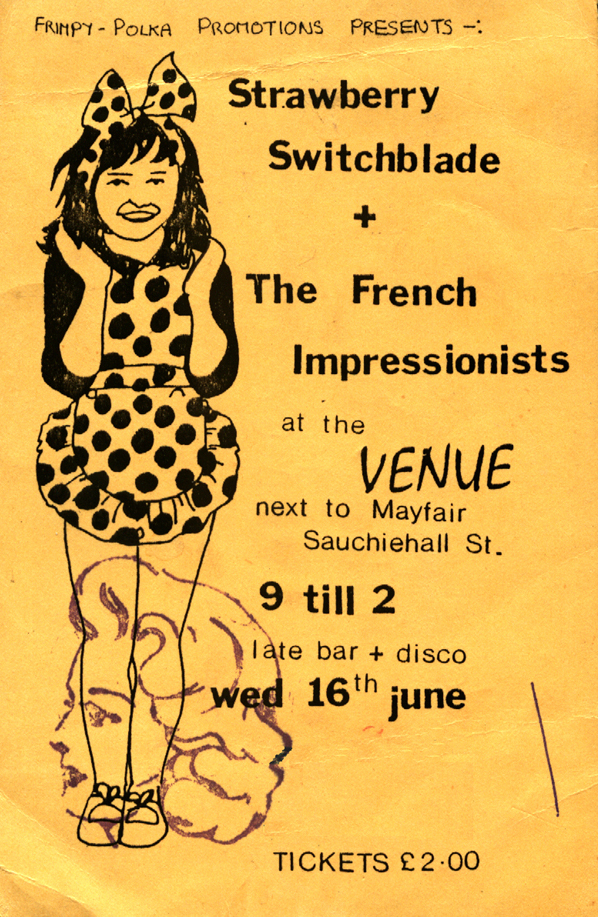

Flyer for Strawberry Switchblade live at The Venue, Glasgow, 16 June 1982, featuring drawing of Jill Bryson as a child. Hear & download the concert in the Live Recordings section of the site.

Q: There’s a tape of one of the really early gigs and there’s a reference to being there and missing the World Cup on TV, which would make that summer 1982. How long did Strawberry Switchblade last as a four-piece?

Rose: God, not very long at all. Until Strawberry Switchblade started getting really busy actually. We became a two-piece when we started doing the Peel sessions [it was a little earlier – NME dated 7 August 1982 said it had already happened]. I was still going to do Poems things but it was getting a bit silly cos I was practising all the time with Strawberry Switchblade. And also I had a daughter so Drew, my partner at the time, he would be babysitting while I was doing Strawberry Switchblade things.

Eventually The Poems thing just kind of fell away, cos also the guitarist got married and stuff and it just dissipated really. Drew had wanted to carry it on but it just didn’t work, we wouldn’t have had enough time to do it all. Didn’t have time to do all the Strawberry Switchblade, never mind anything else!

We sat down and thought ‘we really want to concentrate on the band now, and practise a lot and do gigs’. And we sat down with the other two girls and said ‘would you be willing to give up your job if we get really busy?’ Jill was at art school at the time, and she was willing to give that up, but the other two girls weren’t willing to give up their jobs.

Q: What were you doing at the time?

Rose: Me? I was not doing anything except being in Strawberry Switchblade and The Poems and listening to bands and being a mother and having fun and going out a lot [laughs]. I wasn’t working, work already was music, I was writing, spending a lot of time doing that.

So they decided they didn’t want to commit themselves to the band, so we thought there’s not much point in continuing [with the other two] cos we now have to continue on our own if we’re going to take it a bit more seriously. And within weeks we had got a call cos Orange Juice had mentioned ‘look out for Strawberry Switchblade’.

Q: How soon did you realise it was going to get that busy? Did you think at the start you were going to make a go of it as a really serious thing?

Rose: No, we just thought ‘let’s join a band and have fun’, cos Orange Juice were our friends, all our friends were in bands, I was in The Poems at the time and it was just really easy. Punk made it really easy to be in a band as well.

When I was a kid growing up that’s what I always wanted to do. I remember in school when the careers officer came round and was asking everyone what they wanted to do, and they were saying they wanted to be a nurse or work in a steel factory or a shipyard, and I said I wanted to be a brain surgeon or a pop star, and everybody in the class just started laughing. I remember when we were first on Top Of The Pops thinking ‘I wonder if any of them are watching now?’

But I remember when I was younger thinking you have to have a manager and you have to do all those kind of things, I hadn’t a clue how you became a pop star or really thought about what that meant, I just wanted to sing cos I always liked singing. I was always singing at the top of my voice along to all my records that were blasting really really loud. None of the neighbours complained, in fact they used to borrow all my records cos I had the best record collection in the street.

My dad started taking me out to buy records when I was 12 years old. He was so much into music he was glad he had a daughter he could take out and buy music for. My first seven inch was Monster Mash! I love it!

Q: The other people in the band: when did they leave and why?

Jill: We didn’t actually play that many gigs with them. I think we must have been together about six months, nine months maybe. I can’t actually remember what happened.

I remember an American woman got involved called Barbara Shaw. I think she was a Postcard fan and she’d come to live in Glasgow and she must’ve known Alan Horne, and Rose got to know her and she said she’d like to be our manager and we thought well, if you want to do that, fine. But then it all started getting a bit weird as soon as she was involved, it all started getting a bit strange.

Q: What kind of strange?

Jill: Well, her and Rose were quite friendly and I think she wanted to get rid of everybody except Rose, basically. At one point she was coming along to rehearsals and playing along with me and I started going ‘what? That’s a bit weird! Why’s she doing that?’ That kind of freaked me out a little bit.

Q: Did you ask what she was doing?

Rose, Jill and Truffle Hunter the cat, Glasgow, probably 1982. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

Jill: Oh, she was ‘just learning to play guitar’. At that point she said that the other two weren’t committed and they weren’t going to do it full-time.

Q: Was that true?

Jill: I don’t know. I don’t think so, I think they were pretty pissed off actually. I can’t actually remember what happened, it had come to a point of ‘do you really want to do this?’, we were going to take it up a gear. I can’t remember exactly what happened, I know it wasn’t very nice.

Q: You’ve said you had problems with not being taken seriously because you weren’t blokes. Would that not be even more of a problem if you’re not a full band playing instruments?

Jill: Yeah! But there was the whole thing that we were writing and we [Jill and Rose] were committed and they [Janice and Carole] weren’t really putting anything into it. But that’s kind of how bands work, really, when I look at it in retrospect. There’s usually ‘just musicians’. And it’s not as if we wanted good musicians! It coincided with this woman being involved, and it set alarm bells ringing with me.

Q: Did you mention it to Rose?

Jill: I did mention it when there was this bizarre moment when Barbara came round to my house and said ‘I think we’ve really got to talk. I really have to talk about the image of the band’. The other two had gone by this point. She said, ‘I think you’ve got to get your own image’, Rose had said ‘Jill’s copying me and I don’t want that’, which was just crap, and also I thought very petty. Obviously she hadn’t really known me and Rose cos anyone who had would’ve known different, I remember telling Orange Juice and us all howling with laughter and thought it was so funny. It was such a silly petty thing to do.

Q: Was that being exaggerated by Barbara or was that how Rose actually felt?

Jill: I think that’s how Rose felt. It’s tricky cos she was brought up in a really kind of deprived area of Glasgow, really deprived. I remember going round to hers and I was actually shocked, there was a mattress burning in the street outside. No cars, people didn’t have cars, just a mattress on fire in the middle of the road and that was just normal.

She’d grown up in that and it was quite scary. There was nothing in the house. She hadn’t stayed on at school or anything, she worked in a cake shop, and because she was hanging round with people who were at college I think she felt at a disadvantage, which nobody else thought. They all thought there was street cred, you know?

I see now that she had a problem in that she felt she wasn’t as well educated or as well read. She wouldn’t know who the Prime Minister was, if you asked her to point out Australia on a map she wouldn’t be able to do it, she’d no idea where countries were. Which is not her fault, it’s not because she wasn’t smart, it’s just because she wasn’t well educated and she’d just left school and gone to work in a cake shop. For some reason she thought that made her less of a person I think, in retrospect. I think that made her very defensive.

As soon as we got that bizarre trying to oust me, it was, ‘well this is our thing, this was our idea’, the whole thing is something that we cooked up together and pushed on and everybody encouraged us as a couple, as a duo. To start ousting somebody before you’ve even done anything’s a bit bizarre. To start telling tales and trying to belittle them is sad, but I think it’s because of her insecurities. I don’t know if she’d think that, but I think that’s probably what it was. And she used to say ‘don’t tell people you’re at art school’ because she’d think that they’d think I was responsible for more of what we were about. She said ‘I don’t think you should mention it in interviews’.

Q: Did she say why she thought that?

Jill: No, no. She said ‘I don’t want to mention that I worked in a cake shop’, which I’d thought was fantastic. All the punks in Glasgow used to go to the shop she worked in and she used to give them out free pies and things. Her and her friend Linda worked there and they were sacked for having blue hair. Nobody had blue hair then, nobody. They took them to a tribunal and got their jobs back and so they had to be reinstated! That’s fantastic, you know! And yet she’s, ‘Don’t mention I worked in a cake shop’.

I was, ‘it’s up to you what you say about your life’. She was quite happy to talk about being brought up on a council estate and all that sort of stuff, but not the cake shop. Why? She was 16, she’d left school young, there’s nothing wrong with it.

Q: Especially when you’ve got a cool story to go with it!

Park Circus in Glasgow, 1982. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

Jill: It was legendary, The Wee Scone Shop, cos there was a pair of punkettes working in it which was weird enough. You’d get all the wee wifeys going in. They could’ve been sacked for giving the pies away but they weren’t, they were sacked for having blue hair which meant they had to be reinstated. It’s fantastic isn’t it?

By the time I knew Rose she’d stopped working there and then I think also having a baby and being stuck out in Paisley and being married, all of a sudden that’s everything gone at 19. After she did the gig with her pregnant stomach sticking out she was out of circulation for ages cos she had a baby to look after. And really until Keri, her daughter, was a bit older she couldn’t do anything. Then she started to come out again and by that time I was living up in the West End and I was at art school. And I guess she thought everyone else is doing OK and having an exciting life .

Q: That’s a phenomenal amount of drive isn’t it?

Jill: Absolutely. She did not lack drive.

Q: With that sort of background, if you feel insecure from it, and then having a kid and everything when you’re still in your teens and finding yourself, and then you’re responsible for the kid as well; to get out there and do a band on top of all that is utterly phenomenal.

Jill: Absolutely. Also with the lack of education, yet she was writing lyrics and doing well. I wish I’d been a bit more understanding at that time. But by the time we’d moved to London and it got huge I just wanted to punch her! It just went to her head and she just wasn’t equipped to deal with it. She wasn’t equipped to deal with success, and it was very difficult to handle.

I spent most of the time in tears once we were signed and had to do stuff. It was no fun, I didn’t want to do it any more. I was ‘what’s the point? I don’t care whether I’m on TV, I don’t care about that crap’. I wanted to do it because I liked her and I liked writing with her and it was funny and we had a laugh, we had a really good laugh. And yet we still managed to do stuff that meant something to us and that we enjoyed doing. There were some great times, some really good times. Playing live.

Q: You’d gigged as a four-piece, but with the other two leaving did it put gigs out of the way?

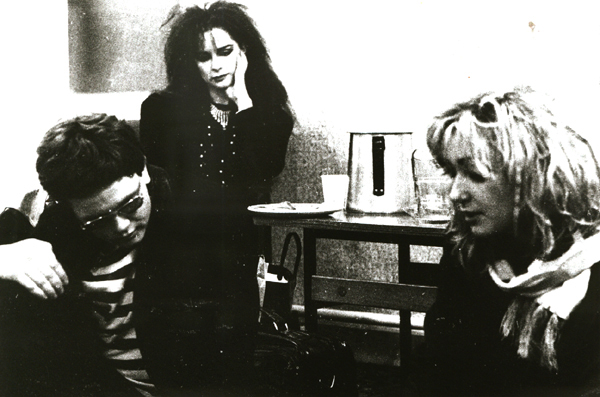

Rose: We started using backing tapes.

Q: Did you start doing that straight away or was that after the records had come out?

Rose: It was before the records came out, we had a reel to reel with basic bass and drums on it. My husband would take care of the reel to reel, he was quite technical, and Jill’s boyfriend’s a photographer so he’d do slides and stuff like that. So, the first tour we did with Orange Juice and we used a reel to reel.

Later on we started getting people in, when we were doing bigger gigs. After the records we’d get musicians in to play, which was a nightmare, I used to hate having the whole audition thing. But we found musicians who we went on tour with and it worked out quite well. And some of the later sessions we did are with those musicians. It was good. We worked with the Madness rhythm section.

Q: What about later touring, didn’t Balfe play keyboards?

Jill: He played keyboards when we played another support tour. We did a support tour with [giggles] Howard Jones! He was on Warner Brothers as well, and we’d signed to WEA [Warner Elektra Atlantic] so they said ‘you’re going touring with Howard Jones’. The only good thing about that was we got to play places like the NEC. Balfe would play keyboards and change the backing cassette.

Q: There’s a reference in one press interview to playing the Royal Albert Hall. What was that?

Jill: [laughs] that was on the Howard Jones tour! [laughs] That was on the Howard Jones tour! It was good in some respects – we got to play the Glasgow Apollo before it got flattened, I’d been to see so many bands in the Apollo, it was great. We did that and we did the NEC which was a bit scary.

Q: The idea of Howard Jones being that big is a bit mad.

Jill: I know! The Albert Hall was the London gig, which was just wild. I’d just recovered from chicken pox as well, so I was a bit spaced out anyway. Backstage in the Albert Hall’s quite a strange thing as well cos it’s really elaborate and there’s lots of space for when it’s used by choirs and orchestras. I’d only done some of that tour cos of the chicken pox.

Q: What happened without you?

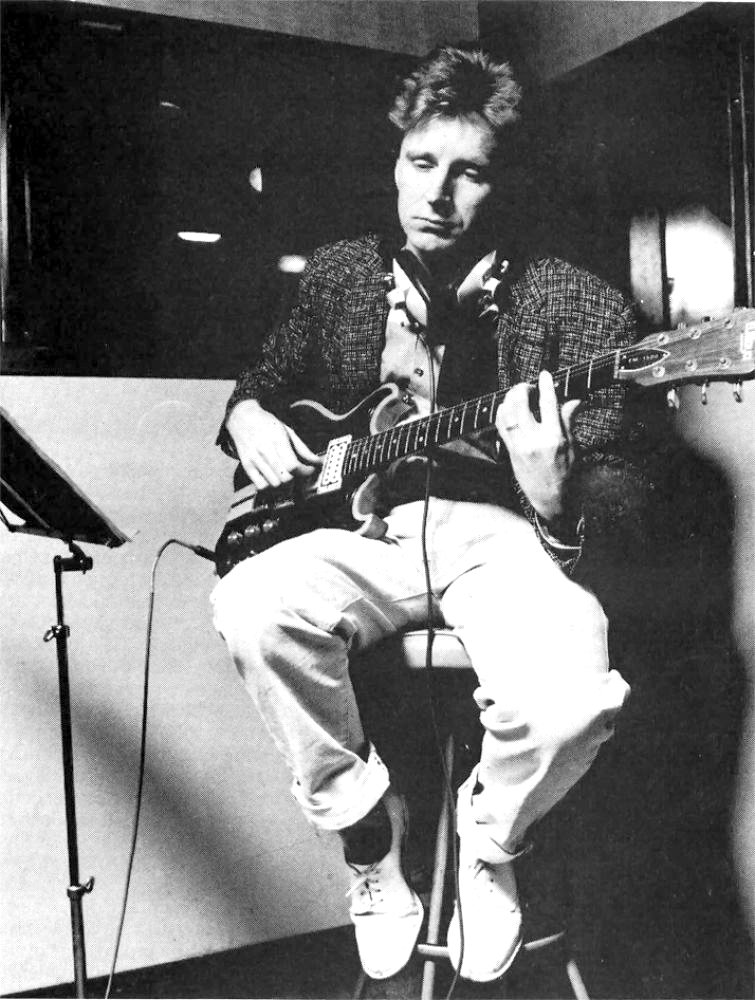

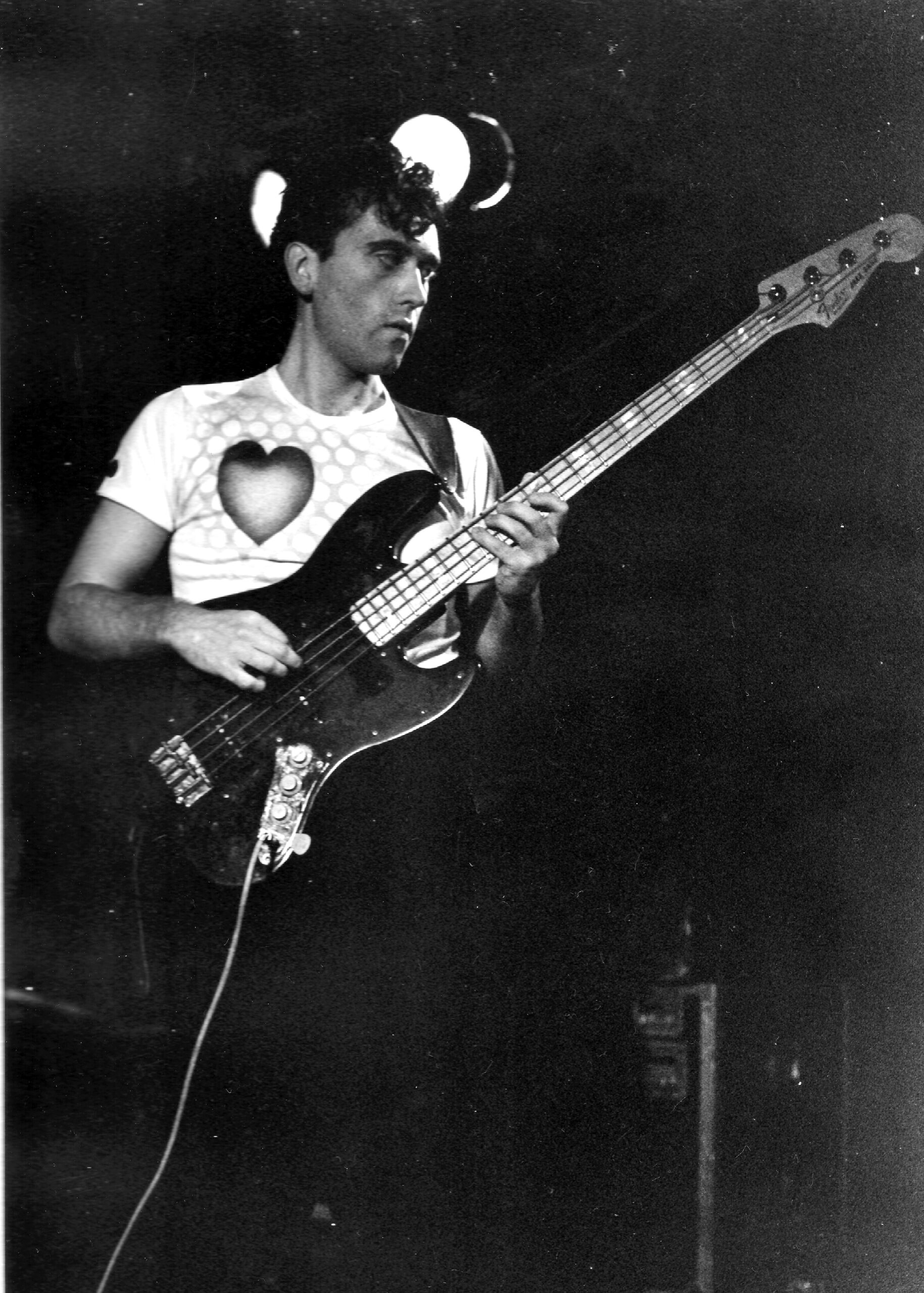

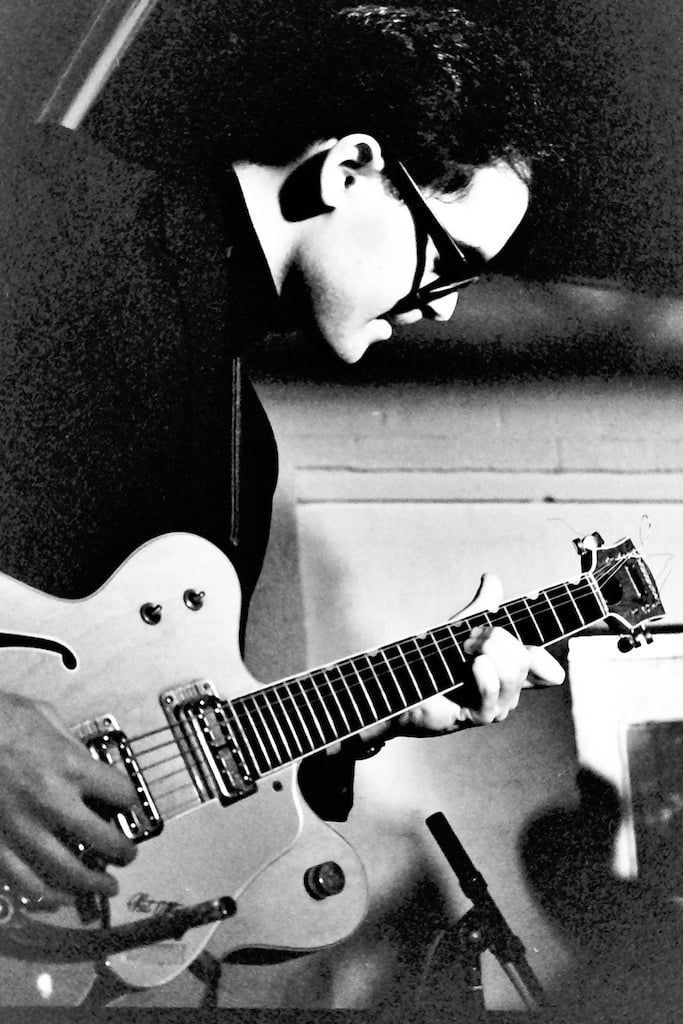

![Jill: 'That's in Stirling supporting the Farmer's Boys in 1983. Very very cold. The bass player was called John. I can't remember his other name cos I'm old and my brain's gone [John Cook]. He played with us with Simon Booth and Roy Dodds and we did the Robin Millar session with them.' 20 October 1983. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.](https://strawberryswitchblade.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/live_stirling83.jpg)

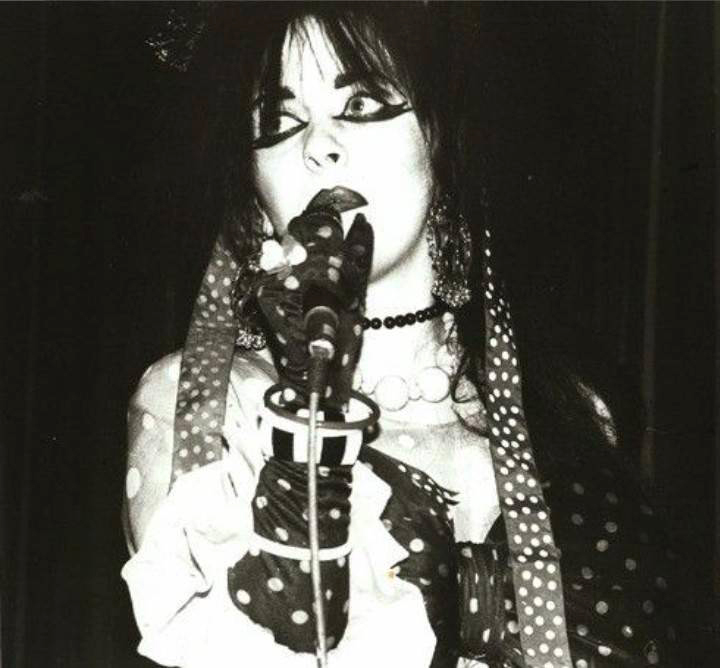

Rose with bassist John Cook, Stirling University, 20 October 1983. Hear and download the full Stirling performance in the Live Recordings section. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

Q: Were you always using backing tapes and programmers?

Jill: We also had a band at one point. I think Madness had split up or they weren’t working or something cos I remember rehearsing with the rhythm section of Madness but it kinda didn’t work, it didn’t sound right. And so then we had this jazz guitarist, a really nice guy Simon Booth he went on to be in a band called Working Week. The drummer Roy Dodds went on to be in Fairground Attraction or something, and there was a bass player, really jazzy kind of players, kinda weird.

Q: I can sort of see it, cos it would be important with Strawberry Switchblade to have musicians who don’t rock.

Jill: That’s it, yeah, that was it.

Q: Not just because it’s important that your records don’t rock but whilst maybe you’d get away with a bit of a noisy guitarist, having a rocking bass player and drummer would kill the subtlety and delicacy. The jazzy thing, at least it’s not rocking, it’s about subtlety and warmth rather than bombast, I can understand why you’d have tried that.

Jill: They were pretty good as well, they didn’t overpower. So we played a few gigs with them but it didn’t really work.

Bill Drummond: Initially Dave Balfe, I think he put a band together round them, an acoustic band with Simon Booth who was the guitarist who then went on and did Working Week. And that didn’t really work I don’t think, particularly.

Their talent was a very delicate talent and could easily be broken with what was around them, and I think on the whole that a traditional putting them on a tour playing small rock clubs around the country just didn’t work. It was too fragile, their thing. Their voices are very fragile voices.

There’s been bands before that have had that problem, there’ll always be bands that have that problem, you put them into a thing where you’ve got a drum kit and a guitarist going through an amplifier and it just starts….

Q: Did you gig much?

Jill: No, not really.

Q: It’s just you’re listing stuff on your own, Howard Jones tour with Balfe, stuff with the jazzy guys, all for a few gigs, it sounds like it adds up to a lot.

Jill: No, it’s just a few here and there.

Q: They played live a bit with the band didn’t they?

David Balfe: Yeah. We did lots of shitty places all round the country, I remember going to Brighton, I remember going to Bath. When I say lots I don’t mean tens but at least half a dozen to a dozen at a guess, but I’m totally guessing. The idea was build up a bit of a fanbase and a bit of awareness.

Also the girls were still very young and they hadn’t really got a lot of performing under their belts, they were still very shy onstage. Well, Jill more so. They could do with the experience to get a bit better as well as building up a bit of a following, get a few journalists down to check them out, just getting those little things that help.

But it costs a lot to put a band together, you’ve got the rehearsal time, paying the musicians, the transport for gigs, every gig costs money. I’d be driving them most of the time. It was a lot of hard work and we weren’t really achieving much because it’s always a bit chicken-and-egg; you put out a single to get a few gigs, you need another single to build on that.

The first BBC radio sessions

Polka dot picnic, Kelvinbridge, Glasgow, 1982. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

Q: So how did you get signed?

Jill: You know, it was just weird, the whole thing was so weird. We’d been playing a few gigs in Glasgow and people obviously thought of it as a weirdo band of its time and place. I think Orange Juice had been signed by that time and it was Jim Kerr. Because he was one of the first Glasgow punks he remembers Rose particularly and I used to go to parties and I’d see Charlie Burchill and Jim Kerr, and they’re very sweet people when you meet them, they’re very nice.

And I don’t really like Simple Minds, but they were being interviewed, I think it was on [Radio 1 show with DJ] Kid Jensen, and he asked them what’s happening in Glasgow, what other bands are good. And he said ‘Strawberry Switchblade, they’re good’, so Kid Jensen’s producer got in touch with us.

We had to pick four songs, and there was only the two of us so we had to get a band together. James Kirk from Orange Juice played bass and we had a guy called Shahid Sarwar, who we all called Shahid StarWars, played drums. He was in a band in Glasgow, I can’t remember what they were called [The Recognitions]. We borrowed him and James and there was another guy who played a little bit of keyboard when we went down there.

Basically it was the four of us and we had to rehearse. And we were all ‘it’s OK, it’s only four songs, we can do it we can do it’, and then John Peel’s producer got in touch with us and said that he wanted us to do a session.

Q: Had he heard the Kid Jensen session?

Jill: No, he just heard that we were doing a session for Kid Jensen, so would we do one for them.

Q: He hadn’t heard you at all?

Jill: No!

Q: Isn’t that weird?

Jill: Yeah, really weird.

Q: Do you know how many tapes Peel gets, and yet he hires people who he’s never heard!

Jill: At that point it was the Peel session you really wanted to get rather than a Jensen session, but we weren’t going to turn down either. So we ended up doing two sessions within about two weeks of each other. We had to have eight songs to do it and we only had six so we had to write another two!

[Those songs would be Little River and 10 James Orr Street – the other six tracks are on a recording of a gig on 16 June 1982].

The Jensen session was a bit more upbeat, the Peel session was a bit quieter. It was just weird, it was wild, absolutely wild. I remember the Jensen session was the first proper recording we did and the producer was Dale Griffin and another guy from Mott The Hoople and I could hardly sit next to them. I could remember them from when I was 14, I was hyperventilating, I could hardly play.

Rose: And we did a John Peel roadshow as well. He used to do roadshows and bands would play. It was just BBC roadshows that DJs would do and there’d be a disco he’d compere or whatever. And he did one in Edinburgh and it was Strawberry Switchblade and Sophisticated Boom Boom, which were another Glasgow all female band at the time. So we did that and we did the John Peel session and then we did the Kid Jensen session. We recorded the Peel one first but Jensen went out first.

[BBC archives say the Peel session was recorded on 4 October 1982 and broadcast on 5 October, Jensen was recorded on 3 October 1982 and broadcast on 7 October]

Q: Did you submit demos or anything?

Rose: No, we didn’t! No, he just phoned my house – not even getting the producer of the show to phone – and said ‘Hi, this is John Peel, do you want to do a session?’ I said ‘do you want us to send a tape?’ and he said, ‘no, that’s OK’. Then David Jensen did it as well just cos John Peel had, they were both trying to be the first one to get us out.

It was mad, everything just happened like that, we weren’t asking for anything, we weren’t pushing. I was going to people and pushing for gigs and stuff like that but not for John Peel to phone up and say ‘do you want to do a session next week? Can you come down?’ Yes! It was bizarre.

Jill: We did that [sessions for Radio 1] and then Bill Drummond, who was Echo & The Bunnymen‘s manager, phoned us and said he’d heard the sessions and wanted to sign us. At that time he was working for Warner Brothers publishing. Him and David Balfe came up to meet us.

David Balfe had been in Teardrop Explodes [also managed by Drummond] and he wanted to get into management. The Teardrop Explodes had just split up, I remember him playing their last album to us, the one that never got released.

Q: It got belatedly released in 1990 as Everyone Wants To Shag The Teardrop Explodes. It’s not very good.

James Kirk of Orange Juice, circa 1979. Kirk gave Strawberry Switchblade their name, played on their first to BBC radio sessions, and sold Rose her trademark Fender Coronado II Antigua guitar. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

Jill: I remember thinking that when I heard it at the time. He was obviously very proud of it, he’d had a lot to do with it.

Rose: Then David Balfe and Bill Drummond heard the sessions, and they came up to Glasgow to meet us and propose that they two would be a management team for us. It ended up that Balfey was our manager solely cos Bill Drummond had to concentrate on running the Bunnymen and they didn’t want him to spread himself out too much.

Q: How did you first hear of Strawberry Switchblade?

Bill Drummond: I knew that was going to be your first question. While you were putting the tape in I was thinking, ‘fuck, when did I first hear of Strawberry Switchblade?’. I think – and I may be wrong – that Dave Balfe, my partner in different things, may have heard a session.

Q: The BBC Peel and Jensen sessions?

Bill Drummond: I think it was the Jensen session. Dave Balfe told me about that and maybe he’d got a tape of it, a tape that included Trees and Flowers [Trees and Flowers was on the Peel session, not the Jensen one recorded the same week]. I remember as soon as I heard that song I thought it was fantastic. Absolutely genius song.

David Balfe: It first began with Bill having heard something being done that came out of John Peel, I think. Bill got hold of a tape and brought it to me and we liked it. I think that was Trees and Flowers but I’m not absolutely sure.

Q: They’d done two BBC radio sessions in the space of a fortnight in late 1982.

David Balfe: I dunno, was it that? It might’ve been that. We got in touch and we offered them a publishing deal. Bill and I had a publishing company, Zoo Music, that had been set up and we’d been doing Echo and The Bunnymen and the Teardrop Explodes with Warner Brothers music. So we did the publishing deal with them.

I was at a little bit of a loose end, the Teardrops having just split up, and I suggested I manage them, and that all seemed to go very well and that’s what we did.

Bill Drummond: So the two of us went up to Glasgow to meet up with them and I think they had an American woman as a manager at the beginning. I think there was some problems there, but I didn’t enter into finding out the detail.

On meeting them, the fact that they had got the whole fuckin look together, the whole package, in that sense added to it. Not just from a cynical commercial point of view, but they just knew what they were about, they were expressing themselves on a lot of different levels other than just writing lyrics and tunes. It was working in a lot of different ways and obviously it was working in a way that could reach out there.

And that look had a genuine artistic depth but also at the same time you knew it could work in a then-Smash Hits way as well. They were the genuine thing, they were real genuine artists.

David Balfe: They also had this image which was very distinctive and very focussed, which I thought would work well and it did work well, but it also had the problem in that very quickly people could see… I mean, it was the classic one-hit wonder in that they had a light and frothy gimmick image, got attention initially but then it didn’t look like it had any depth. And it didn’t really.

So that was it really. Although Bill and I had managed the Bunnymen and the Teardrops together, with the Teardrops ending I was kind of low in self-confidence at that point and it just seemed to be a thing I liked a lot and could get on and do.

Getting signed, Trees and Flowers

David Balfe meets Jill Bryson and Rose McDowall for the first time. The Garage, Sauchiehall Street, Glasgow 1982. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

Q: What were your first impressions on meeting them?

David Balfe: They were a very diverse pair of girls; Rose was very hard, not nastily hard, but she had a very hard working class upbringing and was a tough cookie. And Jill was incredibly soft and quite fragile and had a very nice middle class upbringing.

Rose, when we first met her, was living in this horrible horrible kind of estate made up of blocks of flats on the outskirts of Glasgow, most of the roads weren’t built and it was as desolate as you can imagine any East European housing estate to be, and she’d already had a kid very young.

But it all went together, this soft and fluffy side with the dark and edgy side which I liked the combination of. I liked it artistically and I thought it would be commercial. I thought the name perfectly embodied those aspects, in that Jill was the strawberry and Rose was the switchblade.

Bill Drummond: I genuinely thought they were both equally as talented. What was really good in the blend of their voices, Rose’s voice had that cutting edge to it that Jill’s didn’t. It was a classic Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel thing with the two voices together, even Lennon and McCartney’s voices, when you get those voices that can blend in a certain way, that have different textures and then work together in harmony and you get great pop music out of it. They had that.

But they had that kind of delicate thing which meant it would always be kind of limited in its appeal to a big audience, I guess.

Q: What was the working relationship like between Rose and Jill?

David Balfe: When you’re new to a relationship people tend to club together. They were in the group, they knew each other, whereas I was this guy from the music business who’d been in bands that were successful and stuff. I think they were a bit intimidated by it. So they present a front to you, so you’re never quite sure as the front evaporates over time and you start to see the way things are; is that the way things have always been or is it the way things have gone over recent times?

They worked very closely, it was a bit of a classic sort of Lennon and McCartney thing insofar as when they started I think they were very much excited by working together and fresh, and then as they progressed it became that it’d be one person’s song or the other, I think.

The initial songs were, as much as I could see, worked on together. And they were so friendly with each other, there was not a lot of differences you could generalise about. While Rose was far more the tougher character, they both kind of wanted to do what they did.

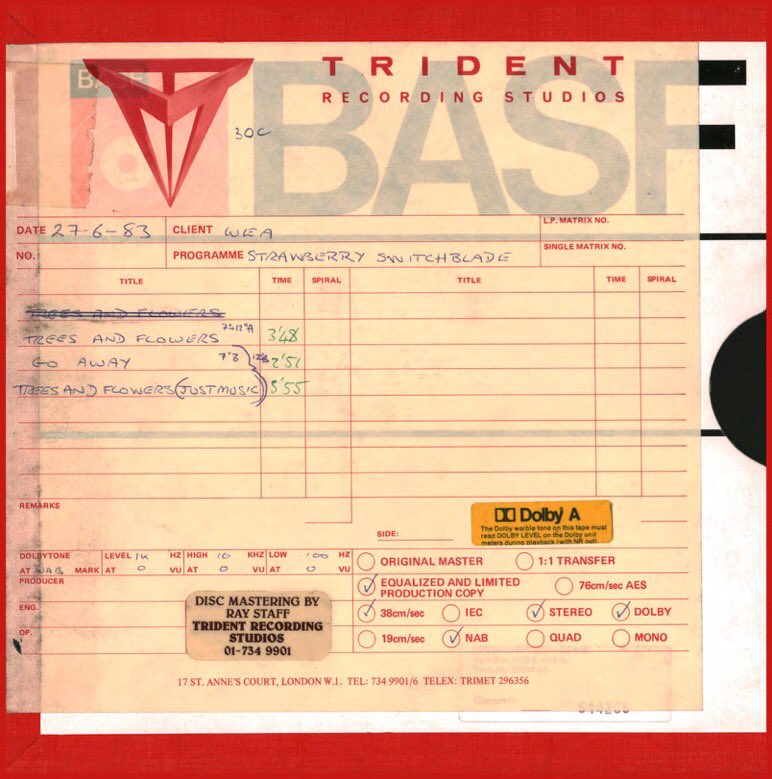

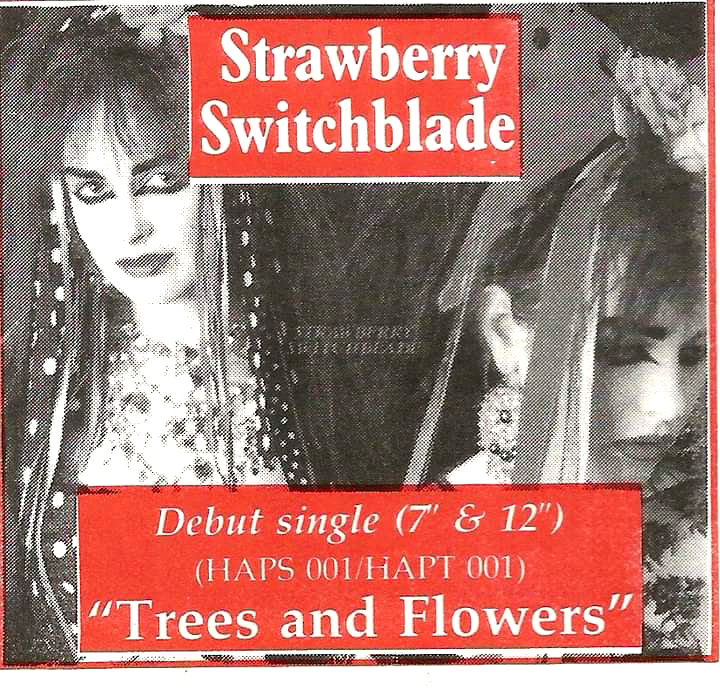

Jill: So, I remember them coming up to see us in somebody’s flat, I think it was Edwyn’s, and they talked to us and said they’d like to sign us to Warner Brothers Publishing, and they’d like to put out a single too. They put out Trees and Flowers on 92 Happy Customers Records.

Q: Was there anything else ever on that label? The catalogue number is HAPS001 which implies it’s a first release.

Rose: Well, that label was Will Sergeant’s from the Bunnymen, I think he might’ve done something on it.

[There was only one other release on the label, Sergeant’s solo album Themes For Grind, released March 1982].

Rose: But basically he wanted to put our first single out as an independent before we went on to a semi-major. He liked Strawberry Switchblade so he wanted to put the record out, and we thought ‘yeah, cool!’. We liked the Bunnymen, so it was mutual.

We were lucky in that sense that we didn’t get just thrown out into the commercial soup of pop straight away. There was a bit of dread, because of the people that we knew and that we were involved with at the beginning like Bill Drummond. It was good to put the first single out as an independent before we went to a major.

Bill Drummond: 92 Happy Customers was Will Sergeant’s label. Dave Balfe and I had stopped doing Zoo Records and I was working with the Bunnymen at the time and Will and I are mates. So we said, ‘do you mind if we put a record out on your label, we’ll actually pay for the stuff,’ and he was really into the record anyway so he was up for it.

He’d done an album on it already of his own stuff, and I think the plan was he was going to do more things. I actually think there was some stuff of his that he was recording about that period that’s just coming out now, in the next month or so, but it won’t be coming out on 92 Happy Customers I don’t think. It’s also a brilliant name for a record label I thought.

Q: Did Trees and Flowers do well?

Jill: It did well as an indie single, yeah. Top ten in the indie charts, and the indie charts at the time did sell quite well. And it was the only single we had that had posters. I remember seeing flyposters round London, we got our picture taken in front of one of them!

Q: Trees and Flowers has got incredible personnel on it; you’ve got the rhythm section of Madness, you’ve got Roddy Frame from Aztec Camera on guitar, you’ve got Nicky Holland who was arranging and performing with Fun Boy Three, and you’ve got Balfe and Drummond producing. It’s laden with major figures from the time, this little first indie single.

Rose: I know! It was good actually. It was lucky, we just happened to be in a scene that was just buzzing with life, so much talent.

Q: I see the connection with Roddy Frame from Postcard Records, but what’s the connection with Madness?

Jill: David Balfe knew them for some reason, I think maybe it was through a girlfriend or something. I remember going out to dinner with people, when we first came down to London once we’d signed they’d go ‘we’re all going out to dinner in this wee place in Camden’ and there’d be several members of Madness there and we’d be going, [incredulous gaping face] ‘this is just bizarre’. I think Balfe had met them, the Teardrops probably came across Madness.

Bill Drummond: I think the record that Dave and I produced, Trees and Flowers, – and I don’t often say this about records I’ve been involved in making – but I still think it’s a fantastic record. And I think we were able to capture that fragility on that first single. There’s a friend of ours who played cor anglais,. Kate St John, and that really worked well.

Q: Roddy Frame’s guitar works really well to get that blend of richness and fragility.

Bill Drummond: I can’t remember him being on there! I’m not denying it. I can’t remember him being in the studio.

Q: How did it get so many notable musicians on it?

Bill Drummond: The rhythm section from Madness were friends. Roddy was a sort of friend at the time, and I guess he was a friend of theirs [Rose and Jill], but I knew him anyway. The thing is I can’t remember him playing on it!

Rose: It was good actually. It was lucky, we just happened to be in a scene that was just buzzing with life, so much talent.

Bill Drummond: I’m really really genuinely a hundred percent proud of that record. Then the trouble started, I guess.

Jill: Bill Drummond and David Balfe had moved to London at that time. Bill Drummond is such a gab and he’s so enthusiastic, he would get to know people, the pair of them were like that. And Bill had been managing the Bunnymen for a good while and wanted to branch out, so he was an A&R man in Warners publishing.

When they signed us we had to go to London to see them and I couldn’t get on the train cos I was so agoraphobic. I could get out and about in Glasgow but the thought of getting on the train… I remember my boyfriend Peter and Rose’s husband went, and Peter asked the managing director of Warners publishing to borrow a fiver so he could get back to the station! And they still signed us!

Then we got a support slot with Orange Juice. We did this tour with Orange Juice and half way through we signed the contract with Warners publishing, in Liverpool. Then the single was released.