John Cook (bass, 1983-4) interview

6 November 2024

In the 20-odd years since this fansite was launched, the internet has changed everything. Not only is it easy to find pretty much anyone, but you can watch them chat with each other. I saw John Cook reminiscing with Rose McDowall on the Strawberry Switchblade Facebook group.

In the 20-odd years since this fansite was launched, the internet has changed everything. Not only is it easy to find pretty much anyone, but you can watch them chat with each other. I saw John Cook reminiscing with Rose McDowall on the Strawberry Switchblade Facebook group.

In late 1983, Strawberry Switchblade recruited additional musicians to become a live gigging band again. Guitarist Simon Emmerson (aka Simon Booth) brought in Scritti Politti’s Tom Morley on drums, and ex-Angels One 5 bassist John Cook.

After an abortive recording session, Morley was swapped out for Roy Dodds, and that line-up went on to play a bunch of gigs, record a BBC radio session, and make the first recordings intended for the debut album.

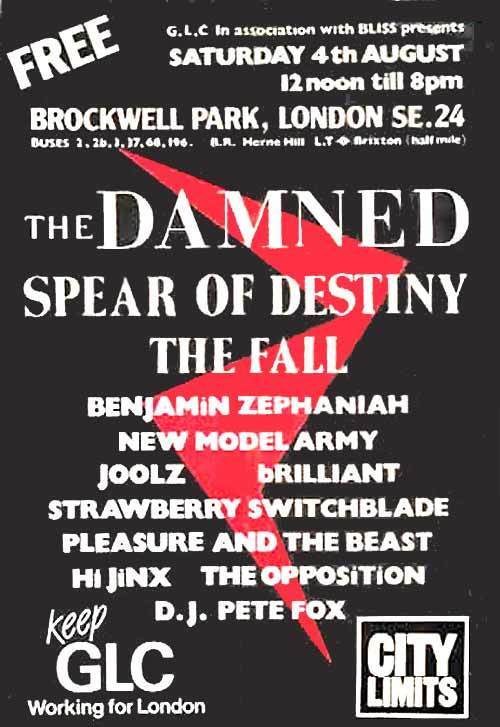

After Rose and Jill opted to go with producer David Motion and dispense with live backing musicians, they did a further gig accompanied by just John Cook and a drum machine – a free one-day festival in London’s Brockwell Park in August 1984.

John’s involvement into the band at the time and analysis of what they did provides a unique perspective on the Strawberry Switchblade story.

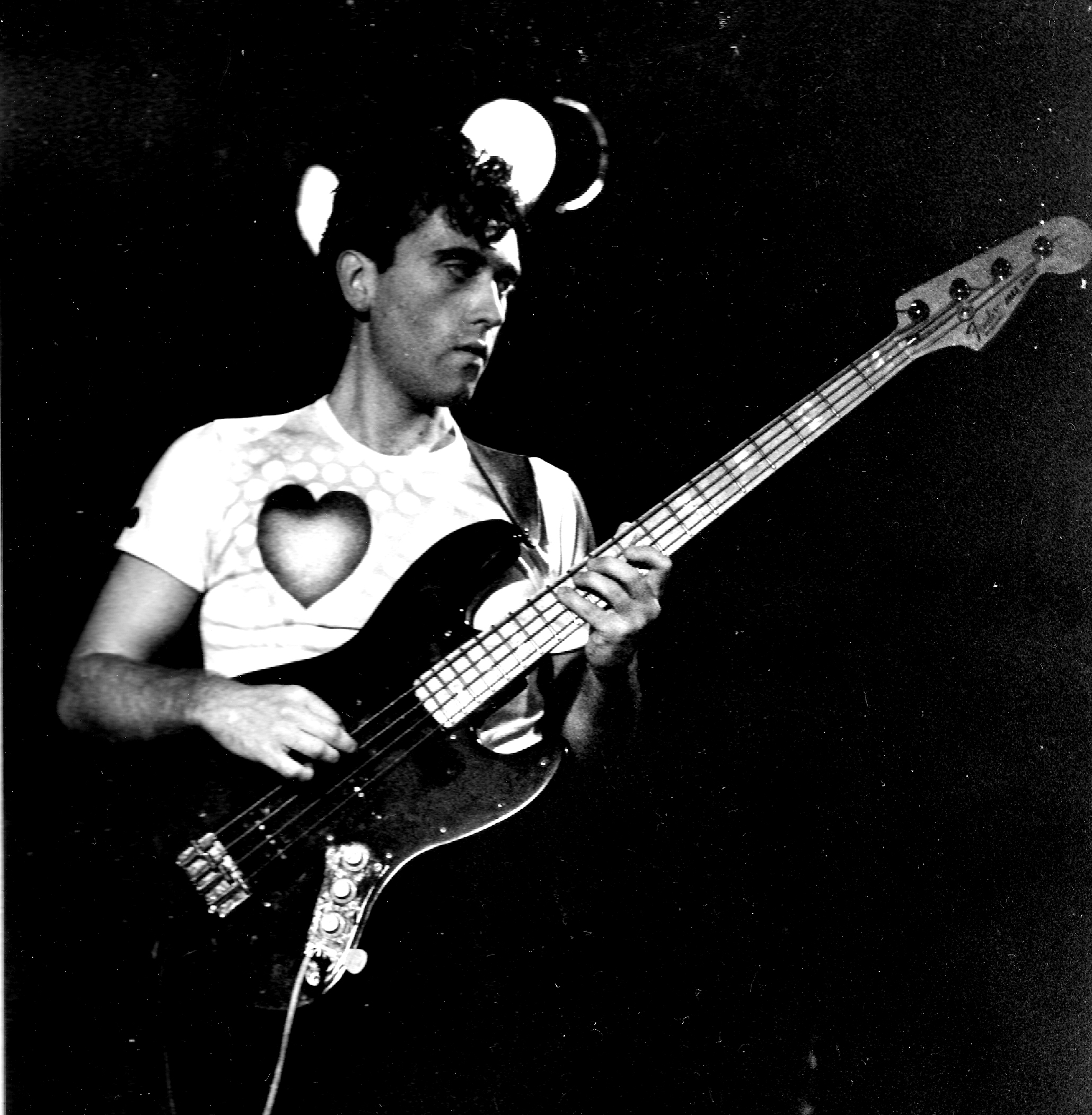

(Pic: John Cook on stage with Strawberry Switchblade, London 6 October 1983. Photo by Halvden Wettre)

Overview, and in the studio

Angels One 5, 1981. Left-right: Martin Cottis (drums, vocals), John Cook (bass, vocals), Cressida Bowyer (vocals), Jimmy Cauty (guitar, vocals)

Q: How did you get involved with Strawberry Switchblade, what was your point of contact?

I moved to London with my mates in 1980 to squat, play in bands, write poetry and be different.

Q: What sort of bands?

Indie bands. The most amazing band with me and my mates, we were called The Popular Russians, which I think is a very good name. And shortly after that, in 1981, I joined a band called Angels One 5. We did a John Peel session in 1981 that he said was one of his favourites of the year [hear the session on YouTube], and in the band we had Jimmy Cauty who went on to form The KLF.

Q: It’s odd how everyone ties together in the Strawberry Switchblade story, with Bill Drummond managing them years before he formed The KLF.

Yes, he went on to do a lot with Bill. I don’t know Bill, I know Jimmy very well – I did do, I’m not in contact with him now. I’m in contact with his partner of the time, Cressida. They had twins together.

I did that for a couple of years until 1982. Where we’d moved to, the squat, was around the corner from Carol Street housing co-op where people from Scritti Politti lived, in particular Tom Morley the drummer. He knew Simon Emmerson who was doing some work with Strawberry Switchblade [using the name Simon Booth at the time].

Simon had worked with Everything But The Girl and he had a band at the time called Working Week. Eventually later, after my time, he formed Afro-Celt Sound System who were brilliant, my kids loved them. I used to go round and practice with Tom Morley because he was a drummer – with the biggest drumsticks I’ve ever seen! He asked Simon if I could get involved in this session work they were doing with Strawberry Switchblade. So Simon said yes. He turned out to be a lovely guy. He’s sadly passed away, but he was a lovely guy.

What we were doing was some kind of session work for Nicky Holland, and Dave Balfe had organised that. I notice from your interviews that he’s always talking about former girlfriends, well she was a former girlfriend.

We went to Amersham where Nicky lived, she was quite well-to-do. She was a formally trained musician, she’d been to music college.

Q: She’d done the arrangement on Trees and Flowers, which is this incredible thing with oboes and French horns and stuff and yet still subtle and understated. It was logical to go with her for the next sessions having done such a great job on the first single.

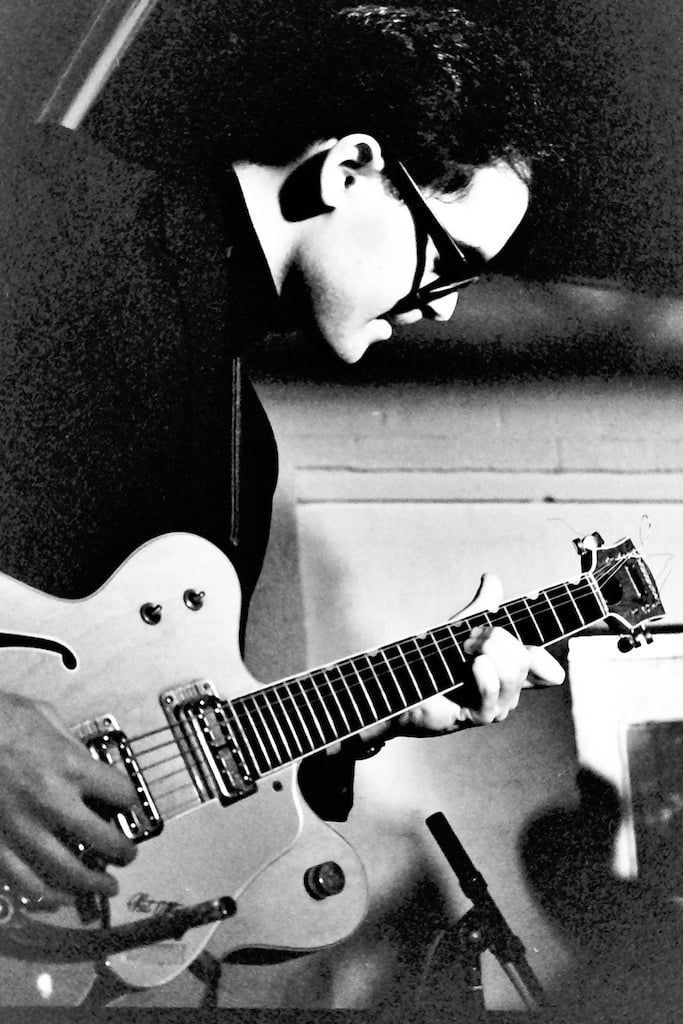

Simon Emmerson (aka Simon Booth), guitarist with Strawberry Switchblade 1983-4, on stage with the band. Pic: Halvdan Wettre

I’d forgotten that. It was a good single, that. So she was producing, Tom Morley was doing drum programming I think, he wasn’t drumming. It was quite hard work for me because at the time I was a DIY musician, that stuff wasn’t my background.

But that didn’t really work out. They pulled in Roy Dodds as a drummer, so me, Simon and Roy were like a backing band for Rose and Jill for about nine months, we did about a dozen gigs. We did the Janice Long session, we did the Robin Millar sessions. And then I did Brockwell Park on 4 August 1984, just me and Rose and Jill with Drew on drum machine, which was a hilarious gig. I’ve been writing about that in some academic work. So that’s a potted history of it all.

Q: Let’s take that piece by piece. So the Nicky Holland session was your first involvement?

Yes.

Q: Do you remember which songs were being recorded?

I wish I could but I can’t, no.

[A Melody Maker feature dated 8 October 1983 reported that Let Her Go was being recorded as the next single and ‘sessions for that album are currently taking place using the same musicians who play on the new single. They include Weekend’s Simon Booth (guitar), Scritti’s Tom (drums) and John Cook on bass.’]

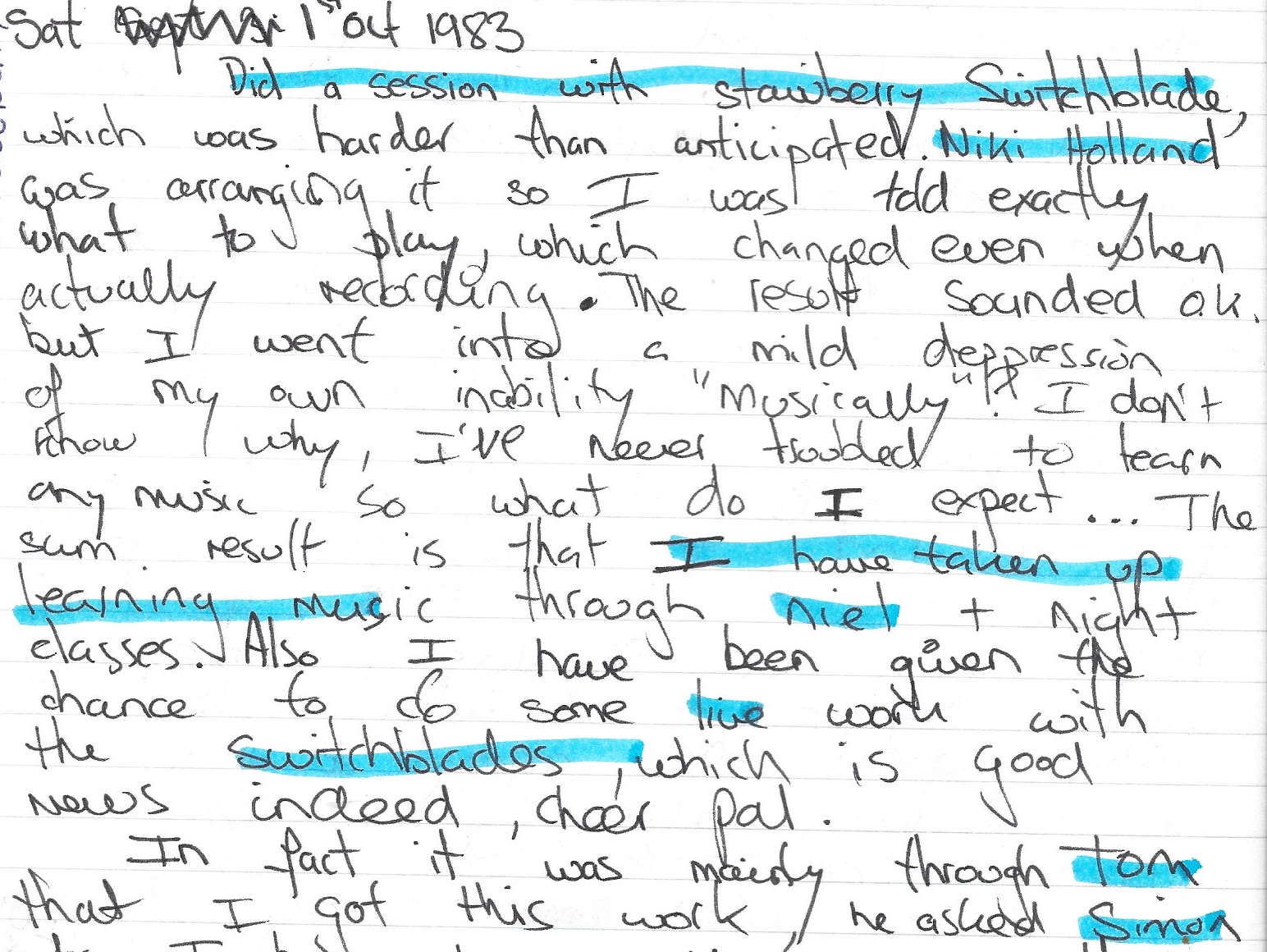

I did keep a diary at the time, not very detailed. And most of the diary is just writing about how I felt about some women. But I did make an entry about this session, and I remember getting a bit depressed because some of the stuff she was asking me to do was quite technical and I didn’t have a music background. In fact, I’m a computer scientist, by the time I got to this squatting I already had a first degree in computer science. I’m difficult to pin down, but I was a self-taught musician. I can’t remember what the songs were at all, no.

Q: So why didn’t it work out with Nicky Holland? Did she have different expectations and standards from what happened? What was going on?

Good question. The people who took those decisions were Simon, Dave, Rose and Jill. And I don’t really know why. I don’t think they thought it was real enough. It was interesting, but I don’t know.

I successfully completed the session and started taking bass lessons with Nial Jinks – who also lived with Tom, and was also in Scritti Politti – but he just wanted to teach me a bit of theory so I gave up on that quite quickly, that wasn’t going to get me anywhere.

I really can’t remember what happened. All I do remember is that it was a good, fun gigging band. We went everywhere from Brighton to Scotland to playing at the ICA. But I cannot for the life of me remember why [the recording with Holland didn’t go further] and I wasn’t involved in the discussions. I was like a glorified session musician. It was a bit more than that cos they were very nice, Rose and Jill. They’d made us feel very friendly and part of the band. And Simon was a good musical conduit because he was a very good musician.

Q: So was it Simon who pulled it all together between everyone?

Simon did pull it all together musically, yes, because he had a strong guitar sound. You can hear that on the Janice Long session, and on the Robin Millar sessions. I noticed in your interview it was a bit too lightweight for Dave Balfe, but it sounded like the Byrds, really, kind of 60s.

Q: And also these almost Johnny Marr touches to it too.

And that was Simon. And Roy was a very good drummer. And to be fair, I was and am a very good bass player – and I am more technical now because I play jazz. I can’t think why that didn’t go forward. I tended to be in it for the – I mean, I remember towards the end I forgot to claim money, I was just doing it because I enjoyed it, really. There’s quite a few conversations about money in those interviews, I wasn’t paying much attention to money. We were doing it because it was really interesting to do.

Q: I think it became an issue later on, once they’d had this bloom of success and tax bills came in, but that’s a long way post-Since Yesterday. Balfe made a fair point that if the two of them were going to be a gigging prospect then they needed additional musicians with them and that meant generating money to a higher level.

It is a fair point, yes.

Q: The Nicky Holland sessions, could you put a date on that? Would your diary have that?

John Cook’s diary entry of 1 October 1983, describing his first recording session with Strawberry Switchblade a few days earlier

The diary entry is 1 October 1983, so it will have been a few days before that. I wouldn’t have remembered otherwise, I was too busy getting on with life, having fun, living in this squatting situation. Having a crazy time, really. It was very good fun. Camden Town in the early 80s was good fun, it hadn’t been gentrified yet. There was loads to do, loads of people to hang out with. So anyway, the session will have been a few days before that date, definitely.

Q: Do you know the dates of the Robin Millar sessions?

No, I didn’t make a note of that and I can’t remember it. There are some recordings out there, aren’t there, on your website.

Q: Was it before or after Janice Long [BBC radio session, 23 January 1984]?

Before, but I’m just guessing. No, it would have been before the end, that’s when Simon tended to drop out then. I think Simon had worked with Robin Millar [as guitarist in Weekend before that, and then in Working Week whose debut album was recorded by Millar at that time], and he wasn’t best pleased that we weren’t going in that direction, I don’t think. So maybe that was towards the end, but I really can’t remember.

Q: Regarding the Janice Long session, BBC archives don’t record the personnel.

No, they don’t. But it’s my bass playing, and it’s Roy and Simon. You can hear, it’s definitely us.

Q: And the BBC say it was recorded at the Playhouse Theatre, in Hulme, Manchester.

Yeah, this really lovely old studio. It was like a 1950s version of the Starship Enterprise, all the old kit they had. It was really good, really nice.

Q: The Robin Millar sessions, did it feel like it was a tryout or did it feel like it was the beginning of making an album?

It was the beginning of making an album. That wasn’t cheap – they had their own chef at Robin Millar’s place, so that was quite luxurious for us. Simon would be in another room sometimes, cranking up the guitar, doing stuff. It was really an interesting process to go through. We did two tracks and it felt like we were going to go for it, and then it clearly wasn’t rocky enough for Balfe or the record company, or poppy enough, I don’t know, whatever they thought.

Q: Do you remember what Robin Millar was like and how much he was in control of it?

I really liked him as a person. He was quite on top of it. He’s quite a musical guy. At one point he could hear that I was playing a note that was flat, for the chord I was playing the wrong note. So I overdubbed that, did it more or less first time. He said ‘I’m pleased you got it right, sometimes people are playing these things like it’s a habit forming thing, but you managed to correct it quite quickly’.

As I mentioned earlier I remember Simon Emmerson on his own in a huge room with the guitar really cranked up to get a good guitar sound. And obviously he [Millar] was quite posh having a chef. I actually grew up in a restaurant, my parents’ one in Yorkshire eventually, then ran a pub then a restaurant for Whitbread’s, I was used to chefs. But it was nice to go in and do some music and have people cook some lovely food for you. It was a very nice experience. I remember him [Millar] being one of the good guys.

I find it hilarious that he can’t remember who played bass on what, I don’t think Dave Balfe can remember my name either. The thing is, I didn’t really go into music, I stopped after that and went into academia, so I wasn’t around to reinforce my name, as it were.

Q: With the results of the Millar sessions not being released, nobody had thought about it for 20-odd years at the time I spoke to them in those interviews. People also had some very definite memories about who played on what that were provably wrong. Robin was sketchy about quite a few of the details, don’t take it personally!

According to them I was either in Young Marble Giants – who were a great band – or the Farmer’s Boys or something like that, according to Balfey. It’s quite funny.

But yeah, Robin Millar, he was alright, he’s a good guy. I can’t remember much about what Rose and Jill did. Did we lay down backing tracks? I think we probably did, then they sang over it when we weren’t there. But the results, having listened back to them of late, were quite good.

Q: Was Millar arranging things? Was he just trying to record what you already did, or was he trying to create something new and get people to do different things?

I got the impression that he worked with Simon a bit on this, that side of things. They’d swap notes and then they’d enact something. I got the impression that Simon was quite invested in that. He did get a sound like the Byrds, which was a very good sound, a very 1960s poppy sound as I’ve mentioned.

Rose, as it comes out in Dave’s interview, is quite strong – which is good! – and so she would come up with thoughts anyway. Their stuff is quite fixed, it’s words and melodies, so maybe, thinking back, it was Simon and Robin who’d swap notes on how they thought the music should go.

Q: It sounds like Simon was something of a musical director for the broader sound, then.

From my perspective it was, I don’t know if that’s really what happened. He had this band, Working Week, which was a big jazz band. And I used to take the mickey, I remember he said to me once ‘you don’t think I’m a good guitarist, do you, John?’ because he used to practice his scales all the time and you weren’t meant to do that when you were post-punk. But he was a good guitarist, a very good guitarist.

I got the feeling it was Simon. I do remember at the time, Tom asked Simon to get me involved, so it was all down to Simon, Simon was calling the shots.

Playing live, and life with the band

Q: You said you were playing for nine months there.

In total, with the Nicky Holland sessions, I played ten months. It was very occasional, I can’t even remember how we contacted each other cos we didn’t have mobile phones. But we clearly did somehow manage. I think I got the messages through Tom saying to phone Simon.

We did quite a few gigs and remember them being good fun. Nottingham, Strathclyde, Brighton. Any gig between 1 October [1983] and towards the end of 1984, we were the backing band.

Q: So was the ICA on 6 October 1983 your first one?

Yes. I’ve got a picture of me playing bass on that. Tom Morley made me a T shirt with a big heart on. It was great fun doing the ICA, I remember that well.

Q: In my Strawberry Switchblade gigs list, the next one is Stirling University on 20 October 1983 supporting the Farmers Boys.

There’s a nice picture of me there with a nice coloured shirt, which I think you’ve got.

Q: They seem quite irregular, rather than a tour – 5 November Brighton Escape Club, 12 November Reading University, 15 November at Nottingham Rock City with Specimen and The Box. Given the sporadic nature of the gigs, how much rehearsing would happen? Was it just to prepare for gigs or was it a regular thing?

I’m having trouble remembering, but probably a couple of rehearsals before each gig.

Q: Were they writing many new songs for you to learn?

There were new songs. Sometimes I think Simon went and played with them, I seem to remember. He’d sort out the chords and then tell us what was going on. Whether or not they were writing much, I don’t know. They did have quite a backlog when we met them. We tended to play similar songs, Secrets and things like that. So the set, once it was together, was similar sort of songs. Sorry I can’t remember much about it, it’s over 40 years ago.

My diary, as I say, was useless, it’s only got a few things in there. I remember the Escape Club in Brighton and I’ve got a diary entry for there, ‘we played well but the audience was a bit muted so that kind of spoiled it’. We got a good reaction sometimes, but not always. But they were writing some new material, yes.

Q: The songs themselves, were there any that you particularly liked or disliked?

James Orr Street, I always liked that cos it’s nice and moody. That was quite an old one. And that’s where Rose used to live. I quite liked the Robin Millar sessions, I was quite surprised when we got pulled on that. I thought they were quite poppy. I was into Siouxsie and the Banshees and Gang of Four, so I was into slightly heavier stuff, but they were good pop songs.

Q: What did the creative relationship between Rose and Jill look like to you?

We didn’t see much tension. It was explained to us that Jill had agoraphobia, which can mean all sorts of things, but it meant for her that she didn’t like to go out much really, and that travelling was a bit of an issue for her, and that one of the earlier songs, Trees and Flowers, is about that. It seemed to be quite a productive relationship.

The thing is, I was kind of a young person with a big black quiff and I got on with them really well, so on a personal level I tended to operate like I was in a gang. I wasn’t really being a professional musician, I was in there just to have a good time and play a bit of music. It was quite fascinating to be with two young women with polka dots on who I found quite creative, and certainly the Peel sessions were good.

![Jill: 'That's in Stirling supporting the Farmer's Boys in 1983. Very very cold. The bass player was called John. I can't remember his other name cos I'm old and my brain's gone [John Cook]. He played with us with Simon Booth and Roy Dodds and we did the Robin Millar session with them.' 20 October 1983. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.](https://strawberryswitchblade.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/live_stirling83.jpg)

Rose McDowall and John Cook, Stirling University supporting the Farmer’s Boys, 20 October 1983. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

I always did get the impression – which has come through in later things in the Guardian and what have you, there’s an interesting 2015 article about Rose – that Rose was the more fascinating one, just from my personal perspective, she did seem to write some interesting lyrics. Jill was very friendly, and eventually they both ended up living round the corner from me in Muswell Hill, so I occasionally heard from them then.

I still think some of the lyrics are interesting, and some of the early stuff was very good, and some of the stuff we did too. I don’t quite agree with Dave [Balfe], he calls a lot of it fey. Yeah the tracks are a bit fey but that can be appealing, that lightness of touch. I mean, Nico didn’t belt it out, did she? But she was an amazing artist.

Q: And it’s the different emotions that you weave together, it’s too simplistic to characterise them as one thing. The whole point was to mix these delicate harmonies with dark undercurrents, heavy lyrical themes with a delicate, almost fragile sound. It’s the contrast woven together that makes them interesting.

Yeah, I agree. There was a good review – because I’ve been researching into that period – and there’s a good review in the NME from Susan Williams in 1984 describing the Brockwell Park gig saying ‘Strawberry Switchblade blast delightfully melodic golden pop – so sweet, so deliciously syrupy – as the sun burst through the scudding clouds.’

She’s being slightly over the top, but they’re scathing about others. I’d forgotten how rude NME journalists were!

Q: It’s amazing! I’ve transcribed over 100 music press articles from that era and across the board there’s this acidic cynical assumptions underlying their writing. That 1980s idea that everything is marketing, everything is being done to try to sell you a product, and this was their unquestioned assumption about music. They write as if bands sit down and calculate what music will sell best, and that they’re making music they hate but just want it to sell. The dismissal and sneeriness of it, there’s a Smash Hits one where they get a reader to do the singles reviews, the lad’s only 12 but even he’s like that!

My friends were a bit like that when they did write-ups too. So, some people liked it, other reviews made negative comments about them. They had to put up with quite a lot, I think, Rose and Jill. At Brockwell Park they got sexist chanting. There were lots of bottles flying and when I did do some memories about that on the Strawberry Switchblade group, Rose did comment ‘that’s right John, I got hit by one of those bottles’ but she was just pleased it hit her hip and not her guitar, this nice Fender Antigua guitar!

They were different times, certainly a lot more violent.

Q: There’s a longer-term patriarchal element as well, the idea that men are violent and that’s what they do, and it doesn’t take much to get men to be aggressive. These days that’s a bit less accepted.

Rose McDowall and Jill Bryson on stage with guitarist Simon Emmerson (aka Simon Booth) in the background. Pic by Halvdan Wettre.

There was a lot of youth unemployment at the time, the miners’ strike was going on but then they lost, and Margaret Thatcher was on the rise. You’d got the free-market economy taking over the UK, so it was a weird time. Creative, very creative, we got so many bands, indie bands in particular, but it was a strange, violent time.

Q: With the wider group around Strawberry Switchblade, who did you see being involved? Were Drew McDowall and Peter McArthur [Rose and Jill’s partners] around a lot?

Always. And Rose and Drew’s baby. I always remember them being quite amusing, obviously Peter’s very amusing and he’s made contact again recently. I just remember them being quite amusing chaps.

Q: And so the gigs and the touring went with those folks as an entourage?

Yes, Rose and Jill with their partners, Dave Balfe driving obviously, and me, Simon, and Roy on drums. That was the unit that went everywhere.

Q: With Drew and Peter coming along for the gigs as well?

I think they did. Peter would have done as he took photographs. I’m not sure Drew would every time because who would look after the kid otherwise? But I can’t remember that part very well.

Q: Peter was definitely there a lot because, as you say, his photos prove it. There’s one of Drew with the band at Stirling, but then that might have been done to tie in with a home visit to Glasgow.

We did, we actually stayed at Rose’s and slept on the floor there, a flat in the high rises up there somewhere. Rose came from, was it the Gorbals or something like that, she used to carry a knife and had to stab someone once to protect herself, apparently.

Q: The stories of her growing up are horrific, her little brother got murdered, just from getting a kicking. It’s absolutely terrifying stuff. The caricature image of Glasgow that our generation of English people grew up with, a lot of it was real and she lived it as a kid.

She went through it. It made me respect her even more because I grew up in West Yorkshire a bit, and there was a lot of violence there. It wasn’t quite as bad as that, we didn’t carry knives.

Q: Whereabouts were you?

Well, I’m a gamekeeper’s son, so I was born in West Yorkshire but we moved around all over the country, but I grew up in West Yorkshire around Leeds and Bradford.

Because I went off and was a student I missed all the F Club [pioneering punk and goth night that ran 1977-82] that happened in Leeds around then.

Bradford had its fair share of problems, but when we started squatting mates came down from Bradford. One of them was Southern Death Cult, we knew Buzz [David Burrows] and Aki [Haq Nawaz Qureshi aka Aki Nawaz]. Ian [Astbury] would turn up sometimes, and I remember him saying to me ‘we’re going to be really big, John’. And he was! He was in The Cult and they were huge. They were lovely lads, actually, and they’re from Bradford.

Q: I didn’t know that!

Buzz was our big mate, he was a very gorgeous guitarist friend in particular of my dearly departed friend Roger. He used to stay in our squat a lot so we got to see Buzz loads. He was a good lad.

Management, and finding the history of the Brockwell Park gig

Strawberry Switchblade – Jill Bryson, John Cook and Rose McDowall – on stage at Brockwell Park, London, 4 August 1984

Q: As well as Rose and Jill’s partners, you said David Balfe was very involved day-to-day.

He did all the management as far as I know.

Q: I’d heard it started out as Balfe and Drummond managing the band together but Drummond moved on to an A&R job at WEA Records. He was already gone by October 1983 when you joined, then?

By the time we got involved we met Drummond once, but it was all Dave Balfe.

And it was interesting to hear Balfe’s thoughts on how he was going to make money, cos I do find in interesting seeing how bands transition from being indie bands to the big time. Scritti did it quite well, from being on Rough Trade to larger labels. As did the Gang Of Four, did it really well. And came up with product as well, I mean good musical creativity and political statements in both their cases.

It’s a bit of a shame that didn’t really work [with Strawberry Switchblade]. All you have to do is look at the Jesus and Mary Chain, they were interviewed in Mojo just recently. They were on WEA, the same record label as Strawberry Switchblade, and they talked to Rose and Jill and were told the horror stories of coming in the next day and hearing things they just didn’t recognise, so they had to fight to make the records they wanted. They [the Jesus and Mary Chain] were quite good at getting drunk and kicking up a fuss by the sound of it! But they had to fight to not let that kind of thing happen to them and keep control. It’s all memories, the same as I’ve done with my memories, we forget what really happened and so they’re interpreting it, but it’s interesting nevertheless. There’s a common theme of what was going on at WEA with management.

And clearly Dave Balfe pulled a few… I remember coming off a gig at Brockwell Park [4 August 1984], we had a meeting after it. We’d been bottled and heckled and all sorts. And at the band meeting later Dave says ‘well John, you just about got it together’. The girls told him off for that. He was quite a sod. I’ve yet to read Julian Cope’s book, but from what you’ve said in your article I can imagine some of it’s quite true.

I find him a fascinating character because he has navigated the music industry fairly successfully. He signed Blur, then he resigned and left them, and they wrote a song about him, Country House. He used to tell me ‘yeah, from the Teardrop Explodes I bought this house’. And fair enough, that was a big achievement at that age. Just gone a bit random on you there, sorry!

Q: Cope’s autobiography comes as two volumes in one cover, Head On and Repossessed, it’s well worth it, it’s hilarious.

I will read them, I meant to before. I know a lot of people who were up there – Yorkshire’s quite macho and Liverpool… we once did a gig in Liverpool and after it these young lads came up and said to Rose and Jill ‘why don’t you hire us for your band? These lot are rubbish,’ and we’re just stood right there. That was very funny. Sods! The Scouser humour.

Q: You mentioned reading the Balfe interview on the site. Is there anything you feel is inaccurate or missing from the interviews that are on the site already?

Personally I was fascinated with your questions around Rose having some Nazi memorabilia, and I’ve heard the stories of Genesis P-Orridge. And Balfey gives a nice perspective on it, because he clearly knew people involved like Stevo, his mate who was Soft Cell’s manager. Personally, I’m researching that, I would like to hear more about that. But that’s just me, I ended up being a research professor.

I’ve just a got a journal article coming out on Strawberry Switchblade, the Brockwell Park gig [final version but paywalled, or draft version with a few errors but free]. I’ve called it a cold case from 1984, that’s the first part of the title. And because everyone has trouble remembering, I take a forensic approach, I look at memory and try to reconstruct what happened from various contemporary newspaper reviews, even if they are from Sounds, and my own diary which is non-existent for that particular event but I’ve got it for other events.

With Angels One 5 we played the Brixton riots reconciliation gig but we got bottled off the stage because we were the only white band. That was with Jimmy and Cressida. But we got a thank you letter from the committee afterwards! But I want to go talk to Cressida and try to dig into that as well.

So anyway, that is from my perspective, which is quite niche, because I’m looking at how Suggsy and Madness and Chas Smash. I went to the Top Rank in 1979 and saw the Two Tone tour with the Specials, Madness and Selecter, then all the skinheads tipped up. I didn’t realise that the neo-Nazis were on the rise and getting recruited.

And then I found out that Joy Division and Siouxsie Sioux were using the names of things, and Siouxsie and Sid Vicious sported swastikas because they thought it was ironic or they were fetishising these insignia. But was it naive, actually? I think it was, because then the far-right turned up.

Q: Johnny Rotten wore a swastika too, in the Pretty Vacant video he’s wearing a Vivienne Westwood ‘destroy’ shirt with a huge swastika on his chest.

And in Slash magazine, a fanzine from 1979, there’s an interview with Siouxsie Sioux. The interviewer tries to pin her down, but she said she was just trying to shock. But then there’s another article that goes on to say that the original lyrics to Love in a Void were a bit antisemitic [the song did have an antisemitic line that was changed before release]. Why were they doing this?

Q: Rose worked with Boyd Rice who’s definitely been far-right adjacent, but from what digging into it I’ve done, it appears that those folks generally weren’t proper Nazis, more that it was done to be transgressive, trying out things that were forbidden and taboo. Rice’s stuff seems more like trolling than anything else. Not that I’m making any excuses for using those tropes and imagery, nor what it can encourage.

And why was there so much violence in music at that time? It’s interesting that it all kind of stopped in 1988. Acid house came in and everyone dropped ecstasy and started dancing together. It really was that, ‘let’s take some drugs and dance together,’ they’re not going to fight.

Q: Football hooliganism, which had been a major problem for a long time, largely stopped at the same time for the same reason, those lads were doing pills and it changed behaviours.

That was an amazing period of time.

Q: You said Brockwell Park in August 1984 was your last gig with Strawberry Switchblade. It’s clearly something you’ve thought a lot about. Why has it been such a big subject for you?

I was a research professor for many years, I then switched from my subject area of education and computing into trying to do some of what’s called autoethnography. Which is where you recount, it’s my experiences interpreted – that’s the ‘graphy’ bit – and I’m interpreting cultural experiences I’ve been through.

I was a research professor for many years, I then switched from my subject area of education and computing into trying to do some of what’s called autoethnography. Which is where you recount, it’s my experiences interpreted – that’s the ‘graphy’ bit – and I’m interpreting cultural experiences I’ve been through.

I tried to do the whole squatting period of four years – and there’s a big document on my hard drive! – but it didn’t quite work. So I thought about that, and I gave a talk at a subcultures conference two years ago where I tried to narrow it down using some theories, and that didn’t really work. So what I then did was, I came up with this loose idea of maybe building on one day. There was a lot of violence at that gig and I just didn’t quite get why. And the more I started to read about it the more I realised it was going on quite a bit.

Growing up in West Yorkshire I was a Leeds United fan, I used to go and see them at Elland Road, and it was quite violent often. And some of my mates were violent as well – I wasn’t, I’m a big softie. So what I thought was, I’ll try and pin it down to one event and try to reconstruct that, and then talk about the wider issues. I kind of did a half-arsed attempt at that and put it into this journal to review, and the reviewers said ‘you should do that more, John’.

So the title, it’s now called A Cold Case, and I’ve gone that way because in cultural historical research they like to look at how myths evolve, and what are the myths knocking around. So for example, punk is commonly held to have originated from rebellious deviant youth – that may or may not be true, but it’s a myth.

What was interesting me about Brockwell Park is, the fact I played there was interesting, but who was doing all the bottle throwing? And then realised as I started to read the reviews that Benjamin Zephaniah got a lot of racial abuse. And I’d forgotten that, and I was a bit embarrassed about that. I did remember watching him.

And then I also saw some of the reviews and realised we got – well, Rose and Jill got – sexist abuse. They got insults hurled at them by variously, I think, skinheads, New Model Army fans, Damned fans. They all got together, got drunk and got pretty outrageous. I remember Ken Livingstone got up to give a talk after us – not after our set but someone else’s – and they threw bottles at him. He picked one up and said ‘no thanks, I’ve got my own’. It got quite ‘tasty’ as they say.

As I read more reports, there was the colonisation of Subway Sect gigs by the far right. They would pick a band and decide that they were their band, even if the band didn’t want it. They had to stand up and say ‘no, we don’t agree with this,’ but then the far right would just trash the gigs.

The violence was there, the skins were there. New Model Army were pretty rowdy. They were from Bradford, apparently.

Q: It’s so weird because they’ve got such a strong egalitarian political agenda and yet there’s always been a huge macho element among their hardcore fans. It may have hanged now because those people will all be in their 50s and 60s, but certainly in the 1980s and 1990s it wasn’t a pleasant experience being anywhere near the front at New Model Army gigs. Totally at odds with the band’s ethics!

To try to narrow down this very difficult process of doing autoethnography, my background is education research with computers and we do case study research, so I used that approach. A cold case is a case study, really. I used case study methods.

Because I couldn’t remember enough stuff for the autoethnography to work. I had some, it was a good starting point, but it wasn’t good enough really.

Also, in 1984, a lot was happening. The miners were just about to lose their strike. There was a guy, I think he was a freelancer for Sounds, David Elliott, and he did a book 1984: British Pop’s Dividing Year. He saw my post on Strawberry Switchblade or Subcultures or one of the groups, and he’s come up with all the bands, indie bands and mainstream bands, what was going on in 1984. He thought it was a pivotal year, and I agree with him.

So that gave even more of a reason to do it, both politically and musically. We had all these indie bands knocking around, over 5,000 he reckons, this strange diversity we had. So it was kind of an exciting time, and a violent time, everything was up in the air. There was high youth unemployment, there was an economic downturn, Thatcherism kicking in.

Q: Something we’ve seen again in the last ten years or so is that when people start expecting the future to be worse than the present it puts this edgy fragility into society, it polarises people. That’s something that was happening under Thatcher, it was clear that for the vast majority of us the immediate future was going to be worse than what we’d had before. It changes how people behave individually and en masse.

It changes for the worse and for the better, though – there was a lot of creativity then. A lot of indie bands. Spiral Scratch [Buzzcocks debut release and big fave of Jill’s] came out in 1977, that was by no means the first indie EP, but it was the one that everyone copied. People like Scritti Politti listed the costs on the back of their single. It started an explosion of creativity which was great.

So it kind of worked as a fulcrum, 4 August 1984. And it was my last gig with them as well, so I was transitioning, that was the last time I played with Strawberry Switchblade. I had an indie band of my own going called Circus Circus, and Balfey had kindly reviewed it. He was quite harsh on it, but that’s fine, that’s what you want, because it stopped me wasting my time really. And it got me used to being an academic where you’ve got peer reviews coming out of your ears and they can be very critical. But Balfe was very fair.

So it was a pivotal time. I then moved into academia slightly after that. It was a pivotal time, it was good to dissect it. And a lot of interesting issues and myths came out of it.

Q: Did you know on the day that it was going to be your last one?

No, I never really got told that kind of stuff, really.

Q: How did it end with you and Strawberry Switchblade? Did you just not get called again or was there a meeting?

We had a meeting with David Motion, I think we met him. I said I was planning on going to Norway skiing with my friend and he said ‘don’t cancel your holiday’.

And then we had another meeting when we hadn’t heard anything, which I think Simon must’ve called or pushed them into it – Balfe, Rose and Jill and me, maybe Roy was there, I can’t remember – where we heard that they were just going to work with David Motion, and he wanted to go in a different direction.

I’d forgotten to claim cancellation fee. I didn’t even know I was supposed to claim it, I was told I could get it but I didn’t claim it. And then Dave Balfe said, ‘well I’ve enquired at the girls’ behest and it’s too late’. They were running at a loss anyway by the sound of it. I was too busy having fun somewhere else really.