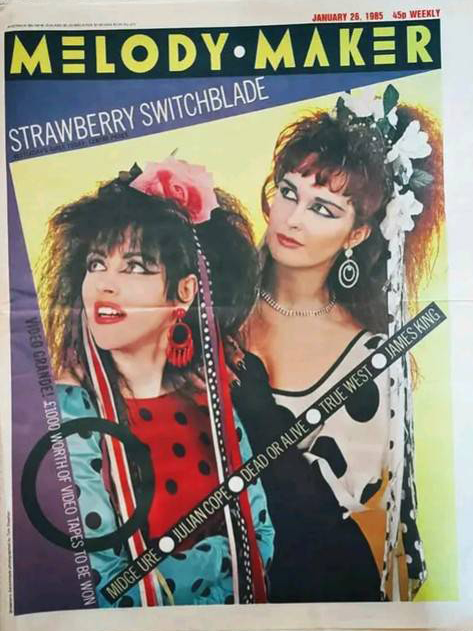

Melody Maker

26 January 1985

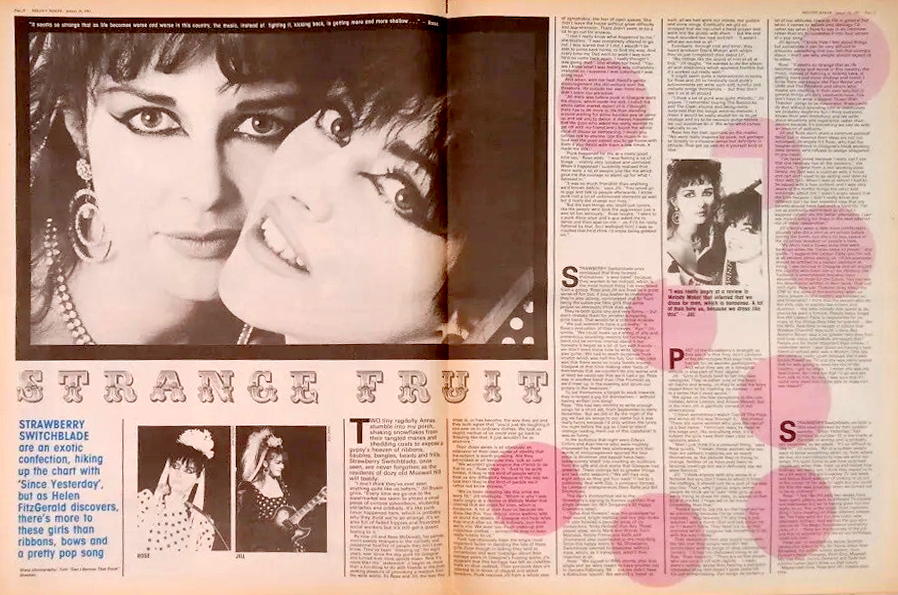

Strawberry Switchblade are an exotic confection, hiking up the chart with ‘Since Yesterday’, but as Helen FitzGerald discovers, there’s more to these girls than ribbons, bows and a pretty pop song.

Two tiny ragdolly Annas stumble into my porch, shaking snowflakes from their tangles manes and shedding coats to expose a gypsy’s heaven of ribbons, baubles, bangles, beads and frills. Strawberry Switchblade, once seen, are never forgotten as the residents of dozy old Muswell Hill will testify.

‘I don’t think they’ve seen anything quite like us before,’ Jill Bryson grins. ‘Every time we go out to the supermarket we seem to attract a small posse of curious schoolboys, muttering old ladies and oddballs. It’s like punk never happened here, which is probably why they think we’re so strange. It’s an area full of faded hippies and frustrated social workers but it’s still got a quaint feeling to it.’

By now Jill and Rose McDowall, her partner, aren’t exactly strangers to the curiosity and occasional hostility of people they don’t even know. They’ve been ‘dressing up’ for eight years, ever since the day punk hit Glasgow and turned their lives upside down. Now it’s more than the ‘statement’ it began as, more than a fun thing to do with friends or the thrill-seeking pleasure of provoking a reaction from the wide world. To Rose and Jill, the way they dress is, or has become, the way they are and they both agree that ‘you’d just die laughing if you saw us in ordinary clothes. We look so stupid, neither of us could ever go back to dressing like that. It just wouldn’t be us anymore.’

Their dress sense is so obviously an extension of their own sense of identity that the subject is worth pursuing. Are they patronised at all because they look so cute?

‘We wouldn’t give anyone the chance to do that to us,’ Rose chips in. ‘And to be quite honest, if they’re the kind of people who’d treat us any differently because of the way we look then they’re the kind of people we’d rather not know anyway.’

‘We’ve been dressing like this since we were 16,’ Jill interrupts, ‘which is why I was really angry at a review in Melody Maker that inferred that we dress for men, which is nonsense. A lot of men hate us because we dress like this. You should come walking with us round the streets of Glasgow and hear what they shout after us. Most ordinary men think we’re vile. We wear too much make-up and ridiculous clothes – sometimes they’ve been really hostile to us.’

Punk has obviously been the single most important factor in deciding the fate of these girls. Even though in talking they tend to romanticise and wax nostalgic about their teenage years in Glasgow’s buzzing scene, it’s apparent that this heritage has left an indelible mark on their outlook. Their pre-punk days are referred to in tones of disgust and abject boredom. Punk rescued Jill from a whole year of agoraphobia; the fear of open spaces. She didn’t leave the house without great difficulty and apprehension. There didn’t seem to be a lot to go out for anyway.

‘I don’t really know what happened to me,’ she blushes. ‘I was completely afeared to go out. I was scared that if I did, I wouldn’t be able to come back home, to find my way. And every time my dad went to work I was sure he’d no come back again. I really thought I was going mad.’ She shakes her head. ‘You see I knew what I was feeling was completely irrational so I suppose I was convinced I was going mad.”

And when, with her best friend’s gentle encouragement she did venture over the threshold, life outside her front door didn’t seem too attractive.

‘All there was before punk in Glasgow were the discos, which made me sick. I hated the whole cattle market aspect of it. I thought there has to be more to life than standing around waiting for some horrible guy to come up and ask you to dance. It always happened that the guys who asked me really wanted to get off with my friend and I found the whole ritual of discos so demeaning. I mean you cannae talk to anyone cos the music is so loud and the guys expect you to go home with them if you dance with them a few times. It made me sick.’

‘Punk happened for me at a really good time too,’ Rose adds. ‘I was feeling a lot of things – mainly very isolated and confused. When it happened I suddenly realised that there were a lot of people just like me which gave me the courage to stand up for what I believed in.’

‘It was so much friendlier than anything we’d known before,’ says Jill. ‘You could go to gigs and talk to people afterwards, I know punk had a lot of unfortunate elements as well but it really did change our lives.’

‘But the bad things you could just ignore, like the people who took the aggression just a wee bit too seriously,’ Rose laughs. ‘I went to a punk disco once and a guy asked me to dance and then spat on me – as if I’d be really flattered by that. So I walloped him! I was so insulted that he’d think I’d enjoy being gobbed on.’

Strawberry Switchblade once confessed that they formed themselves ‘a wee band” because they wanted to be noticed, which is the most honest thing I’ve ever heard from a group. Rose and Jill are fired by a great sense of fun but, if you bother to investigate, they’re also strong, opinionated and far from being the cutesie-pie little girls that some people so obviously think they are.

They’re both quite shy and very funny – but don’t mistake them for another simpering girlie band. That would be a criminal mistake.

‘We just wanted to have a go really,’ is Rose’s evaluation of their motives. ‘Aye,’ Jill smiles. ‘We could make up a string of arty and pretentious sounding reasons for forming a band and be terribly intense about it but honestly it began as a bit of fun with friends – we didn’t even know how to write songs or play guitar. We had to teach ourselves from scratch which was half the fun. Our basic idea was that there were so many bands around Glasgow at that time making utter fools of themselves that we couldn’t do any worse and at least we could say that we’d had a go. Rose was in another band then (The Promise) [sic: actually The Poems] so we’d meet up in the evening and strum our guitars in the bedroom.’

To set themselves a target to work towards they arranged a gig for themselves – without having written one song!

To set themselves a target to work towards they arranged a gig for themselves – without having written one song!

Rose: ‘We had two months to write enough songs for a short set, from September to early November. But we did it! By the night of the gig we had six songs to our name but it was really funny because I’d only written the lyrics the night before the gig so I had to stand onstage reading them out of this copybook! It was so funny.’

In the audience that night were Edwyn Collins and Alan Horne who were mightily impressed by these two scallywags and their words of encouragement spurred the four piece (a drummer and bassist have been subsequently shed) into courting an audience from the café and club scene that Glasgow had spawned. These outings led to greater things and two radio sessions (‘We still only had eight songs so they got four each!’) led to a publishing deal with Zoo, a company formed by Liverpool entrepreneurs Dave Balfe and Bill Drummond.

This duo’s involvement led to the Strawberry’s signing to Korova and their first single release (on Will Sergeant’s 92 Happy Customers label).

‘Trees And Flowers‘was the prototype for their sound, bright melodic and airy pop music – it also boasted a peculiar array of conspirators. Nicky Holland (Fun Boy Three) played oboe, while Mark and Woody from Madness, Roddy Frame and Balfe and Drummond also contributed to the recording. Since this happy event in 83, Strawberry Switchblade seemed to disappear without trace, which, as it transpires, wasn’t their intention at all.

Rose: ‘We signed to WEA shortly after that single and we were meant to have another out in January/February 84 – but we didn’t have a distinctive ‘sound’. We weren’t a ‘band’ as such, all we had were our voices, our guitars and some songs. Eventually we got so annoyed we recruited a band proper and went into the studio with them – but the end result sounded too rock and roll – it wasn’t what we wanted at all.’

Eventually, through trial and error, they found producer David Motion with whom they’ve just completed their debut LP.

‘We didnae like the sound of him at all at first,’ Jill laughs. ‘He wanted to do the album all with electronics which sounded horrible but it’s worked out really well.’

It might seem quite a contradiction in terms for Rose and Jill to heroically laud punk’s achievements yet write such soft, tuneful and melodic songs themselves – but they don’t see it as at all absurd.

‘I think a lot of punk was quite melodic,’ Jill argues. ‘I remember buying the Buzzcocks and The Clash albums and being really surprised that the songs were so melodic. I mean it would be really stupid for us for us to get onstage and try to be raucous guitar heroes – we just couldnae do it. We write what comes naturally to us.’

Rose has her own opinions on the matter: ‘We were really inspired by punk, not perhaps so directly in a musical sense but definitely in attitude. That get up and do it yourself kind of idea.’

Part of Strawberry Switchblade’s strength as they see it is that they don’t conform to the stereotypes that pop/rock music has set for its women participants. And what they see as a renegade attitude is also part of their appeal.

Jill: ‘Girls in bands tend to fall into two categories, they’re either “one of the boys” – all macho and brassy, or they’re what the boys expect them to be (naming no names) – and in a sense that’s even worse.’

We agree on a few exceptions to the rule (notably Annie Lennox and Alison Moyet), but in the main Jill is painfully correct in her observations.

‘I mean sometimes I watch Top Of The Pops and wince all the way through it,’ she moans. ‘There are some women who give the rest of us a bad name.’ Feminism rears its head at this stage and, like everything else, it’s a subject the girls have their own clear cut opinions about.

‘Well I just think it’s a personal thing,’ says Rose quietly. ‘I mean, those women who say men are pathetic creatures are just as sexist themselves as the attitude they’re trying to change. Neither of us have ever been to feminist meetings but we’d definitely say we were feminist.’

Jill: ‘I think anyone with any sense is a feminist but you don’t have to shout it from the rooftops, it should just be a part of the way you live. That’s why I get so angry when people do think we’re ‘cute’ little girls or say we’re trying to dress for men, to appeal to that kind of market. I hope we’re far more interesting than that.’

‘People used to pat me on the head and be so patronising because I’m so small,’ Rose explodes. ‘And because I’m shy they’d just assume I was a dumb idiot and talk to me as if I wasn’t there. They tend not to do that anymore which I suppose has something to do with the way I dress.’

Their defence of their pop sound rests with the fact that they simply wouldn’t feel comfortable writing songs of deep sociological content. ‘I’d feel too dishonest trying to do that,’ Rose explains. ‘There are so few people who can carry it off with dignity – I mean there’s nothing worse than hearing a politically motivated song that doesn’t quite come off, it’s just embarrassing. Our songs do contain a lot of our attitudes towards life in general but when it comes to belief and ideology I’d rather say what I have to say in an interview rather than try to condense it into four verses of a pop song.’

Jill agrees. ‘I know how I feel about things but sometimes it can be very difficult to articulate something that you feel strongly about. I don’t see why people should expect us to either.’

Rose: ‘It seems so strange that as life becomes worse and worse in this country, the music, instead of fighting it, kicking back, is getting more and more shallow and bland. I know there are people like Paul Weller and UB40 and The Redskins others who maybe are revelling in their own way but in general things are very unadventurous. You don’t have to write a blatant ‘Down With Thatcher’ song to be subversive. If we could do that without sounding trite or inarticulate we probably might try but I think everyone knows their own limitations and we write about situations and experience rather than politics because it’s something we can do with an amount of authority.’

Jill and Rose don’t share a common political belief but in essence their ideas are not too estranged. Strangely it’s Rose, who had the tougher childhood in Glasgow’s bleak working-class streets, who refuses to pledge allegiance to any creed.

‘I’ve never voted because I really can’t see that one ideology has all the answers,’ she ventures. ‘I came from a real working-class family, my Dad was a coalman with a horse and cart and I used to go selling coal door to door with him. When I was at school I had to be issued with a free uniform and I was very aware of the hurtful things the other kids would say about me. I wasn’t angry about it at the time because I didn’t really know any different but I do feel resentful now that my parents should have had such a hard life. I’m not as politically committed as Jill but I suppose Labour are the better alternative. I can see myself voting for them in the next election out of sheer desperation.’

Jill’s family were a little more comfortably situated (she did a stint at art school before joining the band), but she’s no less aware of the injustices wreaked on people’s lives.

‘My mum had a flower shop that went bankrupt when the Tories came to power,’ she scoffs. ‘I support the Labour Party and I’m not at all reticent about saying so. I think everyone should be entitled to a certain standard of living. I see families in Glasgow and all a round the country who have five or six children, the husband is unemployed and who have absolutely no hope for the future. You can see the desperation written in their faces. That just isn’t right. How can Thatcher brag about the GNP or the state of the economy when so many people in this country are trodden on and miserable?

‘I think that the people who do the dirty jobs in society like miners and dustmen – the jobs nobody else wants to do, should be paid a fortune. People today forget that the Labour Party is responsible for so many of the things they take for granted – like the NHS. And they’re taught in school that Winston Churchill was such a hero. But Aneurin Bevan was a far greater hero than him and how many schoolkids are taught that? People are far more important than money.

‘I remember when I was about six having a best friend at school who was a Muslim. One day she came in really upset because she’d seen Enoch Powell on TV and she was really scared that he was going to send her out of the country. I got so angry – I mean she was my best friend. So I told her that I’d go and see him, talk to him for her. I was sure that if I could only meet him I’d be able to make him see reason!’

Strawberry Switchblade are both a little shell-shocked by their sudden success. ‘Since Yesterday‘ had climbed to number ten in the charts at the time of writing and is probably still ascending as we speak. ‘It’s so difficult to take in,’ Jill smiles. “All of a sudden people want to know everything about us, from where we buy our hair-ribbons to how we write our songs. It’s quite funny to see how surprised people are when they meet us and realise how ordinary we really are. I think they expect us to be a bit weird. We did breakfast TV last week and Selina Scott was sort of looking at us out of the corner of her eye for ages but you could tell that she was surprised when we turned out to be so ordinary!’

Rose: ‘I feel like the past two weeks have been spent getting taxis to different TV studios and interviews but we’re havng great fun and really, to us, that is the single most important thing. I love meeting all these different people, like Tim Pope who did our new video was absolutely brilliant. And we had the guy who used to do The Magic Roundabout animating parts of it – these are the bonuses of the job and they’re wonderful. It’s like all our birthdays rolled into one!”

These pair of astute Scottish lassies also talked to me for hours about Alan Bleasdale, the public school system, men, Duncan’s Hotel Glasgow, Brian Eno, Muswell Hill, Lou Reed, Donny Osmond and Sade but column inches don’t allow us that luxury.

Maybe next time, Rose and Jill; maybe next time.