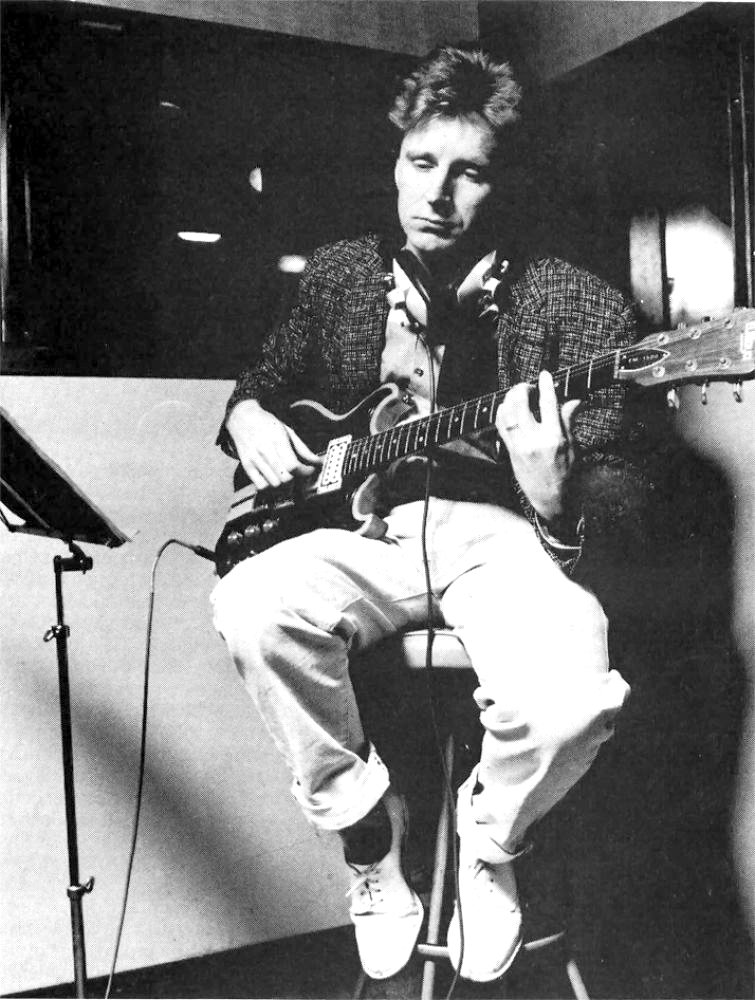

Robin Millar (producer) interview

16 February 2003

Music producer Robin Millar worked with numerous artists in the 1980s including Everything But The Girl, Fine Young Cannibals and Sade. He produced the first recording sessions for the Strawberry Switchblade album, which featured live musicians, and were markedly different from the final electro sound. The recordings were not released at the time.

Music producer Robin Millar worked with numerous artists in the 1980s including Everything But The Girl, Fine Young Cannibals and Sade. He produced the first recording sessions for the Strawberry Switchblade album, which featured live musicians, and were markedly different from the final electro sound. The recordings were not released at the time.

Whilst he is only a bit-player in the Strawberry Switchblade story, his understanding of what was great about the band and his presence of mind in discussing music and creativity make him a compelling interviewee.

Meeting and recording

From the photo session that yielded the Trees and Flowers cover picture, 1983. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

Q: How did you hear of Strawberry Switchblade and get involved with them?

I knew you were going to ask me that! Are you going to tell me or am I going to tell you?

Q: I suspected that your memory mightn’t be clear, it was only a couple of sessions in the middle of 1984, which was a very busy year for you.

1984 was an absolutely extraordinary year for me. Strawberry Switchblade was one of two or three things that I really had a lot of faith in. Them, and another Scottish band called Fruits Of Passion, who had quite a lot of similarity really [with Strawberry Switchblade].

That 12 month period, apart from Fruits Of Passion and Switchblade, for me was Weekend and then Working Week – mixtures of jazz, African influences, good playing, interesting innovative ideas; Everything But The Girl who’d come out of the Marine Girls thing and then Tracey’s own stuff, and they were formulating this bizarre, bizarre hybrid of jazz and at the same time still influenced by people like the Buzzcocks; the end of The Beat and the beginnings of Fine Young Cannibals that I was involved in; and then if you want to go on to a different tip, Sade.

All of these things were basically musician led, band led, flying in the face of programming everything up.

I’m always excited by what I consider to be generic movements which are appearing spontaneously, genuinely from the musicians themselves, whether it’s in the bedroom or the rehearsal room. You do tend to find a flavour in a particular town or country in a particular year.

The Postcard Records thing had appealed to me because of its organicness, its awkwardness, the fact that it didn’t seem to be directly coming from anything that was happening elsewhere, it wasn’t being borrowed, you know? It was almost like the result of a rejection of what was going on, and that’s always been what has appealed to me about that. People who’d organised themselves into some kind of art form that they felt was singular, original, not borrowed from what was going on.

I don’t remember how I… yes I do! I’ll tell you how I met Strawberry Switchblade. It was Geoff Travis, who had had the Raincoats signed up to his label [Rough Trade], or if he hadn’t had them he’d wanted to sign them. The extraordinary thing about Geoff – through whom I met Everything But The Girl and Young Marble Giants and Weekend – he was a man after my own heart in that he just wanted to put people he believed in with other people he believed in who had different skills. He neither knew nor cared whether he would have a financial interest in the results, he was much more interested in driving music on, and he was much more interested in driving through those people who did not seem to wish to commit to the most commercial scene that was going on.

He played me some Raincoats tracks and said, ‘the girl who sang and wrote most of this stuff is now in a new band called Strawberry Switchblade and I think they’re great’. And so it was directly because of Geoff Travis. I don’t remember how the meeting was organised.

Q: That’s odd, I’ve talked to Rose and Jill and the name The Raincoats hasn’t come up at all. Are you sure it’s the same thing? Rose was in a band called The Poems who were very different, a punk band.

I may be misplacing the name. What he may have done was played me two or three things. As I said, my memory is very sketchy about this.

Q: Sure, I’m asking you about a couple of quick sessions twenty years ago!

He used to come to me with anything interesting that he found because he thought I was interesting. You may be quite right. Remember, being blind you get insulated against trying to be too in-full. I always joke with bands I do a whole album with that by the time we’ve finished mixing the album, by then I actually know the names of two or three songs. I just refer to them by a phrase or something. So it’s quite possible, nay probable, that it was just on a tape which said ‘Raincoats’ on it.

Q: They’d had one indie single out at that point, which was recorded with live musicians. Geoff Travis would certainly have spotted that.

He definitely would have effected the meeting.

Q: What were they like to work with?

The thing that I remember about Rose was her sort of twitchy-witchy vibe, her black shawly, white-faced, dark, very… what would you call it? Underground in a way, very alternative but very serious, very deep thinker. Old but young. Very young, but very old in a witchy way. I don’t mean that in a bad way, but kind of sussed.

Jill was very ingenuous and very nice. Being the harmonist and everything, she was very applied. Rose was the pure essence of it, and I thought Jill was necessary for the application of it into some sort of format. I’m not sure that Rose could have done it on her own.

I can arrange and I can write anything people want me to write, but all the ideas pretty well have to come out of the band, out of the artist. I will egg on and coax and try to put them in touch with things in themselves like saying, ‘if there was to be other instrumentation on this song, what are the things that have inspired you recently? what are the sounds?’. If they had musicians who they knew and were part of the plot, I would be reluctant to pass over those musicians, I would tend to try to work with them, even painstakingly if necessary.

Most of these musicians were young, and one thing I liked about them was they hadn’t been in and around studios all their lives. Sometimes it was quite painstaking because I am quite… I’ve never really believed in this particular English… disease, I’d call it, that attitude has to be translated by awkwardness, by a sense of incompetence. Naturalistic yes, but I never really saw why something had to be badly played badly sung and badly mixed to sound real and sound true.

So I would take the musicians as I found them, take the line up of the band as they saw it and kind of beat them into shape if you like, but the same shape, just playing well, well recorded; a little bit of thought into ‘do you really need that bit over that bit cos it gets in the way and makes a mess and you actually don’t get the beauty in each bit – if that’s a beautiful bit let’s hear it’.

Q: It’s a really notable thing that on your version of Secrets, unlike the earlier BBC version and the later David Motion version, there’s a breakdown part where the voices come through.

And that is partly to do with this very kind of churchy thing which Rose sort of gave off, this very black candle holiness sort of thing, and I loved their two voices together. I thought well, if you hear them together at some point in the song then you’ve found the centre of what they are, really. That’s the centre of what they are and everything else can radiate out from there.

The sessions were quick, they didn’t take long.

Q: That’s interesting because they must’ve taken some putting together cos there was only the two of them and the other musicians had to be found. One of them was a guy out of Working Week, Simon Booth, and a bassist and drummer had to be found. Was it your idea they used them?

If you remind me who the musicians were I could tell you.

Q: There was Simon Booth, and Roy Dodds on drums.

He would’ve been from Weekend, I worked with him then.

Q: So it sounds like your suggestions for the other guys.

Yeah. Do you remember who played bass?

Q: No idea, no-one seems to remember.

I think it was Phil Moxon, who was from Young Marble Giants.

[Jill is now absolutely sure it was John Cook, who played bass with them live at that time, and says she’s never heard of Phil Moxon. Subsequent correspondence with Cook himself has confirmed it was him]

They would have had gaps and I would have found people. Like-minded people by the sound of it, cos all the people we mentioned are from interesting, organic music.

It’s also an important thing that, although they’d come out of a punk background and retained the ethic, it was really important with what those songs were that they didn’t have musicians that rocked.

I came out of the punk ethic as well. Punk was what saved me from getting completely hacked off with the music business in the mid 1970s. Thank god I was living in France and New Wave hit France quite early, really – 75, 76 – and that was the first music I ever produced.

I played in a punk band for three years, I produced punk for three or four years and I finished the 1970s playing guitar with Nico from the Velvet Underground for a year and a half. I came back to England fresh out of that, it was with Nico’s band that I came back to London and thought, ‘actually it’s quite nice here, I think I’ll stay here for a while’.

It was straight from there to Young Marble Giants, straight from there to Weekend, straight into Everything But The Girl, Sade, [Fine Young] Cannibals. Not a sequencer in sight, funnily enough.

Although in some of the very early second half of the 1970s French stuff that I was doing reminded me more of the David Motion stuff. So I think there was a ‘been there, done that’ really, and when it started coming into the UK consciousness it just sounded like a group of people had decided to stick Kraftwerk backings on to songs. Which is fine, I liked some of it, but wasn’t interested in doing it, which is why I was flabbergasted when I heard what Strawberry Switchblade became. I didn’t disapprove or anything, because I couldn’t do that, I couldn’t make records like that.

I take it very much as I find it, it’s very organic. As I said, I’m always trying to get the ideas out of the people. Sometimes perhaps that’s wrong, perhaps they want you to sit down and just tell them ‘you should do this, you should do that’. I think it’s a completely different sort of production, that David Motion-Trevor Horn ‘these are the records I make and will fit your style into them’. Whatever else the versions of Poor Hearts and Secrets that I did with them is, it flowed out of them.

And then I suppose what happened was they must have taken those tracks to the powers that be, and the powers that be must’ve said they’re not trendy enough, they’re not where this record label sees its marketing opportunities – ‘do you want to meet this young guy, we’ve just had a hit with him with something else’.

Q: Do you remember it being said that it wasn’t going to go any further?

No.

Q: Was it going to be just do two songs and see how it went, or had there been any plans for anything further? Did it feel like you were gearing up to do an album?

Yes. Yes.

Q: At what point did they say no and back out of that?

You know, it was happening to me all the time. Sometimes, like Fruits Of Passion, Strawberry Switchblade, it didn’t get through the net. The business just said, ‘no no no, we’re totally into electro’.

Q: Do you remember how the band felt at the time about it?

No, because the wall went up. I assume whether out of disappointment, embarrassment or whatever it was, I simply never heard from anyone. And the next thing I heard they were in the studio with Dave Motion.

Changed plans

Q: Do you remember when the sessions themselves were completed and you were listening back to final mixes, were people pleased?

Well that’s usual.

It was a fairly typical music biz scenario, really. There weren’t any people in the control room going, ‘well, it’s not really what we want and have you ever considered doing it with electronic drums or going in a different direction?’. No, it was all, ‘great great great, marvellous, this is brilliant’. And then silence.

Then I heard they were in the studio with Dave Motion, the record came out, the record was a hit. There was nothing I could say about that at all, because that is the name of the game.

I’m also quite used to the business taking a dim view. I did two tracks with Sade which are on Diamond Life, and they were rejected by the record company who paid for them, and so was I; we were all dropped. It was Smooth Operator and Your Love Is King.

It was four months later that another record label picked them up and said to Sade, ‘you should work with this American producer’. If she hadn’t said, ‘if I can’t work with Robin Millar I’m not going to work, I’m not going to sign to you,’ I’d have lost that job as well.

Everything But The Girl, fortunately I had Geoff Travis who was resisting pressure from Warner Brothers who were distributing and marketing Blanco Y Negro Records, who wanted them to go poppier, and he said, ‘no, I’m trying to build a serious career for a serious band’. So you had on the one hand people like him and on the other the RCAs and Sonys who just wanted to go with the flow.

I don’t bother about people who want success, I do bother about people who want success at any price. I actually took part in a panel down at the Medem thing in the south of France where I was talking about the difference to me between an artist and a light entertainer. A light entertainer’s priority is the travel, the celebrity, the handshakes, the loot, and they’ll more or less turn up and do whatever you ask them to do. They’ll be guided by marketing people going, ‘this is a good thing for you to do, so do it’. The artists will not be doing with any of that shit and will determinedly go their own way.

So I was quite used to it happening and I think I had a win-some-lose-some attitude, and I wasn’t that bothered because I wouldn’t have wanted to take Strawberry Switchblade where they ended up going anyway. I wouldn’t have been happy doing them.

I never got any sense from them that they wanted something different from what was going on; that might have been my naïvety, I was pretty naïve as far as UK producing was concerned, I only did things as I felt them. Maybe if I’d sat down and asked them the right questions…but you would’ve thought that somewhere in the conversation electro and sequencers and synths would’ve come up if that’s what they’d wanted.

Q: They’ve said that it was David Motion’s idea and they rolled with it, and Rose said there was this situation where the Powers That Be would say ‘if you’re not entirely happy just give it a chance’, and by the time it’s been given a chance there’s a lot of time and money been invested in it and it’s much more difficult to get out of it. They liked working with David Motion. It shocked them at first, but they liked the result.

It was only later they realised it was part of the plan to make them into this frothier Smash Hits thing which they really didn’t want to do and they really hated, and in the end it pulled them to pieces.

I certainly could have told them that that would happen. It’s so easy to bulldoze young artists into making records that they end up ashamed of and compromised by, that end up painting a picture of them that’s not them.

I absolutely have faith in the fact that I can walk into a room with any artist I’ve worked with will come up and embrace me, say ‘great to see you,’ and something like ‘I still play those tracks we did together’, whether they were hits or not.

![Jill: 'That's in Stirling supporting the Farmer's Boys in 1983. Very very cold. The bass player was called John. I can't remember his other name cos I'm old and my brain's gone [John Cook]. He played with us with Simon Booth and Roy Dodds and we did the Robin Millar session with them.' 20 October 1983. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.](https://strawberryswitchblade.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/live_stirling83.jpg)

Rose on stage with bassist John Cook, Stirling University, 20 October 1983. The band with Cook, Simon Booth and Roy Dodds played on the Robin Millar sessions. Hear and download the full Stirling performance in the Live Recordings section. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

Q: Bowie’s best selling album is Let’s Dance.

Exactly. Spandau Ballet, who were in the same hands as the people who did Alison Moyet, absolutely destroyed their credibility, and even they and they management didn’t really understand. I remember Spandau taking Chrysalis Records to court because True had been a number 13 single and the album hadn’t sold. Quite rightly the case was turned down, and the expert feeling was, well, the track True doesn’t represent Spandau Ballet in any way whatsoever, it’s a pop record made completely on the side; you’re not building a fanbase with it. People will go and buy it and hear three other tracks and go ‘eugh! It’s horrible!’.

[The story is right, if not the record named: Spandau sued Chrysalis in 1985 – after the release of Parade, the successor to 1983’s True, had sold poorly in the USA – alleging that Chrysalis weren’t giving enough promotional support and thereby harming their career. They settled in 1986 and switched labels.]

I’ve never been interested in getting into that.

The records I’ve done that have sold – and there’ve been lots of them – have stood the test of time, are generally organic in nature, generally involve real musicians. And that, as I said earlier, is not because I don’t like that other stuff, it’s just not what I do, it’s not what turns me on.

Some of the records I made sold loads of copies, but they acquire coffee table status, they don’t start out like that. Even Sade, we handed that in and they said ‘what the fuck’s this? What the fuck’s this? It hasn’t got anything to do with what’s going on!’.

Q: If it had sold 20,000 copies it would have been seen as a strange and arty record.

Yes. Precisely.

Q: The musicians you pulled in from Weekend and wherever to work with Strawberry Switchblade, do you know how much time they would have had to put it all together?

Backstage during the Orange Juice support tour, possibly University of Essex, Colchester, 20 November 1982. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

We’d have done it in the studio. We wouldn’t have rehearsed it. If you noticed, the drum parts are very similar to the demos they’d been making. Bass wasn’t a problem. I would have weeded out and sorted out the vocals. And I would have encouraged the guitar ideas to emerge, the guitar themes.

Q: Did the band themselves have very clear ideas about the songs?

No, not particularly. That’s why I’m not particularly surprised they were able to go with David Motion and let him see what he could do.

What I do is to fill in the blanks; I try to get people to come up with ideas and I’ll fill in the blanks where they’ve got them. They were quite inexperienced and they’d just have got a guitarist and a bass player and a drummer to do their radio sessions and probably simply accepted the fact that, ‘oh that’s how the drums go’. But I like that you see, I like things that already come with a direction.

Once again, it might be a failing with me, I don’t immediately just deconstruct what I hear and reconstruct it from the middle outwards, which is what I suspect a Trevor Horn or a David Motion will do. I don’t really get inspired to do that, I have to have something to hang my hat on and it would’ve been those BBC recordings.

I’d have put it on, turned it up, gone into the next room so that I didn’t hear the detail, just the big noise that the track was making. It would’ve been the vocals and those basic drum patterns and some kind of guitarry thing going on. So, true to what we had, really.

And obviously, you could just tell, the ability and the tone and the understanding to do fabulous things with the vocals. Not as fabulous as David did, but it was a different context.

Q: What was the working relationship like between Rose and Jill? How did the dynamics appear to you?

I always thought of the two of them as separate. I thought of Rose definitely as the dominant one. But then there’s always one in a band. It’s not always the singer, but there is always one.

Jill, I didn’t really think of her as a 50-50 part of what was going on, I thought she was an adjunct, like a band member. Although I assumed they must have worked together developing the songs there was very little evidence of momentum from the band themselves, which is why I’m not surprised they would have tended to go with whatever producer they were working with’s idea.

When I meet bands whose music I love and think is very essential, and I also think is challenging what is going on, I think I sometimes put a political spin on things and a resolve which perhaps isn’t really there. It’s something I bestow on artists I think. They were probably just a couple of ambitious young girls who wanted to get ahead by whatever means was going, and I was probably far too politically minded to imagine that from where they’d come from, what the tapes sounded like – it sounded like John Peel land, you know?

Q: I think it’s really interesting you say there was a lack of push from Rose and Jill, because they definitely were coming at it with artistic intent, they definitely were in it for the music, they’d come out of a strong punk then Postcard background. I wonder how much of it was them being daunted by working in proper studios with proper producers, which only a few months earlier would have been unimaginable to them.

I would have thought it was unlikely that working with me posed a challenge to their musical ideas and direction. I’d believe it if they said so and then I’d say I’d done a bad job and that’s quite possible, but all things being equal it would have just flowed naturally out of where they were at that moment, what else they liked.

If I did impose a musician I’d have said, ‘let me play you some other things they’ve done, what do you think of it, would you like to meet them?’. It would all have been very considerate.

I suspect they were already aboard the ever-quickening spiral they were put on by the record company, with more and more decisions being taken for them.

What label were they on?

Q: They were on Korova, Rob Dickins’ imprint at WEA, so it was the full Warners machine that decided they were going to be the next big thing. They had stylists coming in with costumes for them, there was a lot of pushing ideas on them and it was all moving so quickly with a ‘we know what we’re talking about, trust us’ attitude.

Tokyo graffiti. Strawberry Switchblade’s first trip to Japan, 1985. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

I’m not surprised. I remember handing in the first Everything But The Girl album, Eden, to Rob Dickins. Eden went on to really do very well and become an international classic, really. He [Dickins] rang up and he said, and I quote, ‘how come you do a great job for Sony on Sade and you do such a shit job for me?’.

By ‘a shit job’ I think he meant not sounding 80s. Just got some musicians in and done some songs, there’s people strumming guitars and playing organs, where’s all the synths, where’s all the special effects, the Dollar, the Trevor Horn, the ABC, the Simmons drums and glassy digital synthesisers? I’m not surprised at all, I’m not surprised at all.

Q: I think also a lot of the people in charge of them were trying to move up the ladder very quickly and using them as a rung.

Who was managing them?

Q: They signed with Bill Drummond and David Balfe thinking Drummond would be their main one but as it turned out it was Balfe almost entirely. He was very much looking to get into management; the connection at the record company was Rob Dickins who was on his way up at Warners; so it was all people doing that eighties careerism thing rather than anything to do with the artists making good records.

It’s funny that Balfe went full circle in a way and ended up hating anything that didn’t sound like a band had walked into a studio and just played it. He made public speeches about it at record company do’s.

They were in the wrong place at the wrong time. Or right place at the right time; I mean, maybe they’d have never had hits with me. They wouldn’t have had hits with me because they were with Warners and that isn’t what Warners do. I suppose I might have known that at the time if I’d been more experienced. But I still had a rose-tinted view that record company people were like us, and wanted the same things, and wanted to be friends first. The whole point of a life in music is that you can and should be able to have a great time, be with people you like, get on well, not have the usual crap you get from a 9 to 5.

I think it takes quite a while for it to sink in that a lot of people who work at record companies – the ones that stayed there rather than run in go ‘oh my god’ and run and hide – are as unlike you, maybe more unlike you, than the people you meet working down at the benefit office. I’m not sure why or when that happened, but it did happen in the eighties that you met less and less people in record companies who you felt were kindred spirits.

I’d come from France, I’d been in France for six and a half years, and the people I’d met at the record companies in France were like me. They were just music freaks, and they signed acts because they liked them, they released records because they liked them.

If the Smiths had been signed directly to Warners without Geoff in between, the Smiths wouldn’t have been allowed to make records like they made, would they? Not in a million years! And when you actually listen to the work I was doing with Switchblade and then you listen to the Smiths and you think of the nature of the grip and the hold that the Smiths took in the hearts and minds of their fans; that’s where I like my acts to go.

I like my musicians to come from the bedroom, from the rehearsal room, nothing to do with the industry at all. That thing that starts playing to 50 people which becomes a hundred people which becomes a thousand turned away at the door, then it catches on, then you put the records out, then the market finds itself and these people become important, seminal, influential, they become deeply satisfied as well as satisfying.

It may have ended up with Morrissey losing his perspective but he certainly wouldn’t have wished for anything better or different in the type of success. And I think you can hear a direct link from the work I did with Strawberry Switchblade in 1984, and the [Fine Young] Cannibals and where the Smiths were.

It was a very strong direction. There was a very strong culture pushing through, just to have guitar bass and drums, great song ideas, a great sense of belonging to the people who were standing in the audience.

Q: And yet still retaining that feeling of outsiderness from the masses.

Yeah.

And that’s me, I’m an outsider, a child of two immigrant parents. In Paris I was an outsider because I was an immigrant, but there were so many immigrants in Paris and there was so much music that was a cross-fertilisation of different sorts of people who’d come there from different sorts of places. But the UK, there’s a south east London blokey third, fourth, fifth generation sort of thing. The following pubs; you go there. You see the following bands; managed by your mate.

I always have and still do feel completely outside that loop. I’ve been to the Brits once and I just walked around, acutely uncomfortable. I thought, this is my business, what am I doing in my business?

Q: Most people deeply involved in music are outside the Music Industry. In the same way in literature, you can be Kurt Vonnegut or you can be Jackie Collins and you’re in the same business but you’ve nothing to say to each other and only one of you is part of ‘the industry’.

It’s the people who don’t get awards, who don’t belong who make the interesting stuff. The best people on Top Of The Pops are the ones who look the most out of place. Seeing the Jam or the Mary Chain without choreographed moves but giving it tons was how you knew they were for real.

Everything But The Girl refused to go on, because Tracey said she wasn’t going on a show with women dancing in cages in bikinis. They said, ‘but your record’s number 23, it’s going up, you’ve got to do it,’ she said stuff it. And there wasn’t a peep out of me about that. You couldn’t listen to Tracey Thorn’s lyrics and imagine she would do it! It was a ridiculous idea.

But there we are, Strawberry Switchblade and the 1980s Warner Brothers dynasty; that’s chalk and cheese for you. It’s the politics that are interesting.

Music and integrity

Rose on stage at The Warehouse, Leeds, supporting Orange Juice, 1 December 1982. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

Q: It’s a really sad thing because they were there with the talent and the desire, they were making music for all the reasons people should make music; cos they had something to say, they had this little protective gang of themselves that would bond themselves but also fortify the people who understood the music. They had this stuff they wanted to say that was just coming out of them, not for any fame or glory, and this knack for these great darkly beautiful pop songs and gorgeous gorgeous voices, and it was all taken from them – and what they could’ve done taken from all of us – by this corporate steamroller.

And it’s really really wrong-thinking to say that a group like that don’t want to communicate with a large number of people and sell a lot of records – they do. It’s just that they want to sell records to a completely different group of people. Record companies have got their marketing strategies, their radio stations that they’ve got in with, their record shops they’ve got promotional understandings with, their TV people; so the formats limit themselves by the marketing opportunities the record companies have in front of them. In other words, the records are market-driven.

Q: It’s the only way they can have any kind of predictive strategy, because the people that bands with integrity do want to sell to, you can’t make them buy records by glossy promotional techniques, they’re not susceptible to marketing strategies. They can only build the promotional machinery to sell the worthless, unchallenging and dull records.

Can I give you the best example that I can think of? This may sound like a really strange example, but the best example I can think of is the Ferrari motor car. The Ferrari comes directly out of an authentic passionate skill for developing the best racing car in the world. Not selling to supermodels or premiership footballers, just making the best motor car that they can. That’s what they devoted all their passion to, and they started to win some races then people got to hear about them and love them. And everything that is beautifully crafted and efficient tends to have an aesthetic that matches it.

A car that will do 200 miles an hour looks like a car that will do 200 miles an hour, and it looks beautiful. Ferrari have never ever advertised their cars in their history, anywhere. There has never been a magazine ad, a cinema ad or a TV ad for a Ferrari car. And yet it’s the most sought after glamorous vehicle in the world. It’s because what has always driven it and what still drives it is completely and utterly authentic.

The Rolling Stones, even though they couldn’t be less like Ferraris in appearance, are the equivalent. Right from the word go they had dedication, authenticity of purpose and the willingness to go and take it round the world over and over and over again. They will still now pack more football stadiums than any other band in the world because that authenticity still comes through.

Forty years on and still, before every gig, there’s a Moroccan marquee behind the stage where they’ve put the same Indian rug and the same lights, and for forty minutes Ronnie and Keith sit opposite each other on the rug just riffing, so that when they walk on and go ‘1 2 3 4’ they’ve already nailed their groove. That’s real, they don’t do that for the money or the tinsel. They do it because it wouldn’t occur to them not to do it.

That’s the kind of success that I crave for my artists, and I have played no part in any other sort of success because I’ve never seen it last, I’ve never seen it give lasting value to the people in the middle of it.

It’s important to ask the Strawberry Switchblades of the world ‘what if?’, what do they think may have happened. Not necessarily with my productions, could have been someone else’s, but what would have happened if there had been no outsider coming in saying ‘we’re going to process your music in the following way’, that it had all just grown out of them as central figures and they had become as big as the Smiths, which they could have done. How would they feel now? Better. I’m sure Johnny Marr still feels good about himself.

Q: Absolutely. Morrissey still loves those records, Marr’s still really proud of it too. I saw an interview with him recently that asked him if he’d ever had an interview that doesn’t mention the Smiths. He said he keeps doing records, but of course the Smiths will keep coming up because it’s great work.

I went – out of solidarity, not out of great musical interest – to a retrospective of Kirsty MacColl’s life at the Festival Hall, an evening of playing her songs. It was alright, the band were kind of there. And then Johnny Marr came on and plugged in and started playing for five or ten seconds and it was a bolt of lightning had struck the entire band. Suddenly there was this authentic, credible thing, it was like Keith Richards walking on stage. It totally changed the whole evening from that moment on. There was an authority and a certainty and a recognisability about what he did.

This was the one musician on the stage that had never ducked and dived and done what the market wanted. It was the Smiths guitarist and blimey, he’s starting to play, and blimey, it sounds like the Smiths, and all the very credible people on the stage suddenly caught fire.

Q: The guy has done what he believes in for 20 years and been proven right!

And been proven right! Exactly.

My job is to make sure that the setting for the songs and the people singing and playing them is the perfect setting to hold those songs up to the best possible light so they’ll seem at their best and you’ll get the most out of them. And from there I guess you have to try to dig deep to know what it is that you’re trying to get out of them.

It’s not beauty with Strawberry Switchblade, it’s haunting beauty isn’t it? It’s not great harmonies, it’s great requiem harmonies. There’s a sense of inevitability, a sense of patient holy longing. Waiting for something but you’re not sure what it is, and in the meantime you’re not quite in the right place at the moment in this life, that there’s something beyond that you’re reaching out for. And at the same time, you’re a young person trying to have fun, and it’s very difficult.

Q: That is exactly it.

And so you’ve got to come up with a record that is like a bunch of young people trying to have fun, but with this sense of yearning and longing that we’re not really in the right place, we’re not settled. The politics around us, the people running the country, the way some of the other young people are into stuff that we’re not into, gives you that sense of outsiderness and dislocation. But, you are a bunch of young people trying to have fun and so there is going to be an invective in your music that is going to be frisky and immediate, with nice little riffs and good little tunes. It’s that behind the mask thing that, to me, is what’s so marvellous.

What is so brilliant and fantastic about pop music – and I’m never ashamed to say I’m involved in pop music cos I am – the great thing about pop music is that more than anything else I can think of, in three or four minutes you can create something that will mend a broken marriage, that will save a person from dying from a disease, that can make the leaders of a country think again about their foreign policy, that can lead a whole generation into realising that there’s more to life than they thought and compromising is not what you do in your only opportunity on earth.

Films take two hours making heavy weather and are usually very shallow. We don’t have ‘Desert Island Films’ still running after 55 years on Radio 4; we’ve got Desert Island Discs because it doesn’t occur to people to think that a show where you take your eight favourite movies would actually catch the imagination of succeeding generations, but take your eight favourite four minute numbers and people get it immediately, they know exactly.

And they can actually pick eight songs that will encapsulate their youth, their greatest loves, their greatest losses, their greatest hopes, their greatest fears, their greatest achievements all in one go.

Jill Bryson and bassist John Cook on stage at Brockwell Park, London, 4 August 1984. Hear and download the performance in the Live Recordings section, and see the Press section for the Sounds and NME reviews.

What an art and what a difficult skill to create all that in a three or four minute thing that, at the same time, you can just put it on turn it up and run around the house, go yaaaay and it just makes the day feel better.

It’s a great thing, but it’s got nothing to do with following the market and making records by numbers. Hearing those two tracks [recorded with Strawberry Switchblade] I was chuckling actually, because I could just imagine – I’ll have to say imagine rather than remember – how those vocals came to go from where they started to where they ended up with me playing my whimsical, encouraging, exacting part in it.

And I could just imagine how those little guitar riffs on Poor Hearts started as a sound more than anything else, or may have started as a riff and I might have said ‘try that riff on this guitar, play it up the octave’. I was always trying to get people more definite with their ideas, I always thought two or three great ideas were worth a hundred iffy ideas. If this riff’s worth having on this record, let’s make it the riff of the record. It’s not difficult, hearing those tracks, to imagine the process whereby it would have fallen into place with the group of people around.

I’ve got some feeling that there was a sense of unease, a sense of awkwardness somewhere in those sessions, but Rose in particular was slightly unfathomable. And, as I say, maybe what I didn’t know about Rose was that she was more of a commercial go-getter.

Q: I think she’s going to love what you said about ‘black candle holiness’, she’ll adore that. She always had a lot of psychic and magical inclinations, and she’s still very much a pagan spirit.

That’s what I meant by witchy, I don’t mean witchy as an insult.

Q: You can tell with Rose there’s a lot inside her. Regarding the idea of ‘commercial go-getter’, she’s a very very driven woman, but a commercial go-getter is not what she is.

I have to say that even from that scruffy old cassette I think those tracks are no particular credit for me, except for not destroying it, if you know what I mean. I’m terribly concerned not to destroy things when I make peoples record with them. Maybe it doesn’t make them commercial enough sometimes. But I hear that and I can picture her and I can picture Jill, and I think they’re true, they’re true statements of where they were at the time and that had they been exposed to the public and had the public liked them I think they would have been quite happy to carry on doing more and develop it, unless they’d fallen out for other reasons.

I get that sense of the spirituality, I can hear all that, I can hear the Hammer horror scenes on the hill at night time with the black crosses, I can hear it in there. There’s something about that jagged Rickenbacker guitar thing which reminds me of big old ceremonial sword axe type things. I can’t explain what I mean but it does evoke the macabre slightly to me.

Also, it’s timeless. There’s something about that Shakin’ All Over drums thing that gives you a sense of ‘have we been here before? Has this music existed before? Is this strangely evocative of all sorts of things like Johnny Remember Me?’

The fact that I exaggeratedly put Jill’s harmonies into a different and a longer reverb from Rose’s. I don’t know if you noticed that, but it’s not just two voices with the same effects on them. You definitely get the feeling that the other one is just behind and some sort of echo. The face behind the shoulder, as it were; looking over the shoulder but unseen by the singer somehow. Some essence of the singer’s facing front and behind her is another version of herself, the harmony is another version of herself, slightly different but unseen by her. She seems focussed and intent on singing what’s going on in front. You don’t get any sense of them being face to face, or even side by side.

You have to say that if that’s the way I set them, that’s the way I saw them. There’s no doubt about that. If that’s the way I set them, which I definitely did on those tracks, I definitely must have seen them not as standing side by side, but as Rose standing in the front and Jill slightly behind, slightly to the side, looking in the same direction but mostly unseen.

The last Strawberry Switchblade photo session, just weeks before the split in June 1986. Pic used by kind permission of Peter Anthony McArthur, who retains copyright.

You shouldn’t define your career by the records you sell, not in any sense. One of the really nice things about conceptual art is that you mount the piece for the duration of an exhibition and then you sweep it up into bin bags at the end, and it’s gone. That doesn’t devalue it as art because it’s the process of creation and then getting some people to experience it the way you want.

The time they spent in the studio with the BBC, the time they spent in the studio with me, the time they spent with David Motion, to me they’re all periods of their life.

Herbie Hancock I suppose leads a slightly more comfortable life than he would’ve done because in 20 minutes as a joke he wrote Watermelon Man before going on stage, because a friend was described as having a head like a watermelon. He literally went over to the piano and went ‘heeey, watermelon man’, and that was it.

But I don’t suppose for a minute if you talk to Herbie Hancock about the highs and lows of his musical journey he’ll discuss Watermelon Man. He’ll mention it as being a good meal ticket but it won’t form any important part, it was just something he did for twenty minutes. It sold a lot of records and it’s paid for a lot of suits.

So, in a way, if they fell out as a result of music industry pressures, they should take a deep breath and they should take a longer view. They should say all music careers last a finite amount of time and we did some very interesting things together and we had a very interesting adventure together from an extraordinary fortuitous beginning, and then this fascinating rollercoaster ride where we were able to explore and to develop all sorts of different ways and work with all sorts of different people and then we had a short period of unpleasantness near the end where we felt rather compromised and it got on top of us. But there’s no value to an ex-husband and an ex-wife hating each other ten years later. None whatsoever. You have to say we liked each other enough to get married once, let’s try to step back.

Just listening to the Peel things and the demos and the stuff they did with me and the excitement when they first went into the studio with David Motion; if they drew a line after that, they had a good time, really.

Q: That’s the way they still see it. They’ve both got regrets about the way it ended, but they’re both very clear that it was worth it and they’re still proud of what they did musically and creatively. The David Motion stuff, while it was pushing them into something that could be commercialised, it was still clearly not a Nick Kamen album or anything.

No.

Q: It didn’t kill those songs at all, and there’s still a lot of quirkiness and mystery and twistedness in that record, even though it’s a shiny pop record.

Oh yeah.

Q: The record is flawed but there’s a lot that still captivates in it, and they still recognise that.

If they draw a line after that but before the industry went bananas.

It just makes you wonder about the ineptitude of Warner Brothers at that time, doesn’t it? How could they not have sat down and had a half-hour conversation with the two of them and thought, ‘well it’s completely inappropriate what we’ve got planned for them in terms of marketing and presentation’.

Q: Or even if they had have had that crap from Warners, if they’d only had a manager who’d fight their corner. But they had one who was fixated on how much money could be made, how many magazines they could be in, how much they could get on TV. The fact that the magazines were things like Look In and My Guy meant they were just asked about make up and clothes, and that forced a shallow image on them.

You’ll have to ask Rose why I associate her with the Raincoats. There is a reason that I can’t remember. She might know, she might just say ‘no idea’.

Q: It may be like you said, that Geoff Travis happened to fill up a Raincoats cassette with a couple of Strawberry Switchblade tracks.

It’s something more than that.