Rockstar

July 1985

The original Italian is below this English translation.

The original Italian is below this English translation.

Strawberry Switchblade: Funny Girls

By Guido Harari

Without the polka dots, the Strawberry Switchblade would never have made it to the market. If they hadn’t invented such a rare design, it wouldn’t have been possible to admire these two little girls who amuse themselves by hiding behind two unseemly people and pretending to be sad, enchanted and amazed by the clamour that suddenly surrounded them. A precise design and the rediscovery of the same type of pop that noble predecessors such as Gerry Goffin and Carole King instead deliver them for what they are: good, astute and a little bit sly.

That slob of a taxi driver won’t shut up for a second, ‘Hey, Muswell Hill? This address is not new to me. Is it a band? Hey, isn’t it those two weird little girls, whatever their names are?’, and off he goes about the time the Frankies puked in his car (‘they were just starting out and lived in that little hotel over there‘) and how cute Bronski Beat are (‘Larry lives a couple of blocks from my house’). He can’t even stop himself once the meter is off in front of an anonymous diarrhoea-coloured block (‘it must be flat 2, or 9, I don’t know. I took a TV crew there the other week, blablabla’) and it takes a hefty tip to get him out of the way.

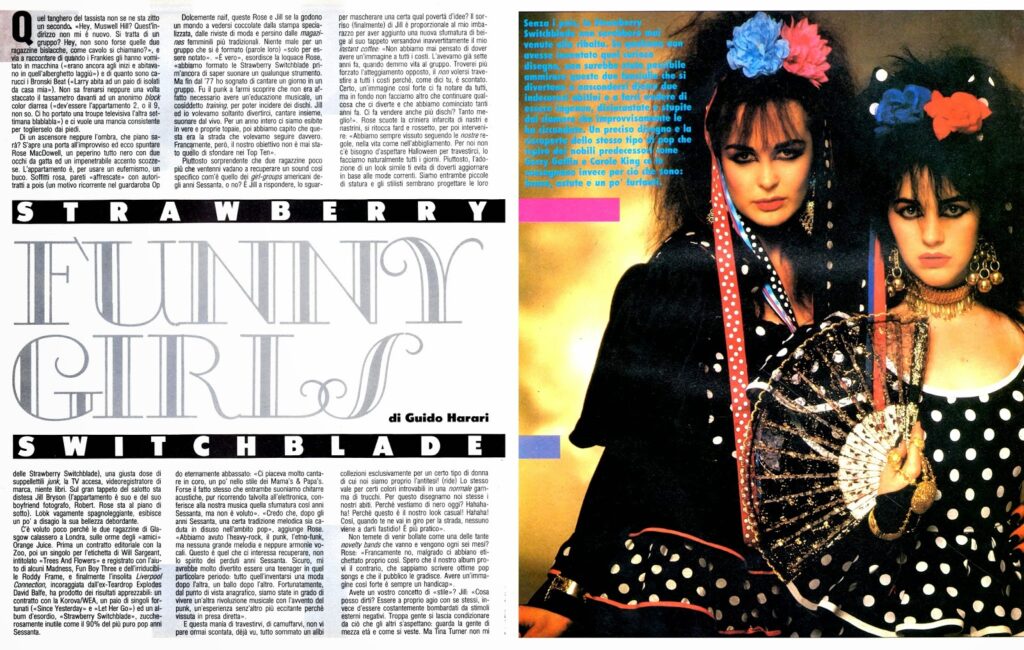

Not even a shadow of a lift, which floor will it be? Suddenly a door opens and in walks Rose MacDowell [sic], an all-black pepper with two cat-like eyes and an impenetrable Scottish accent. The flat is, to put it mildly, a hole. Pink ceilings, walls ‘frescoed’ with polka-dot self-portraits (a recurring motif in the wardrobe of of Strawberry Switchblade), a fair amount of junk furnishings, the TV on, branded VCR, no books.

On the large living room carpet lies Jill Bryson (the flat is hers and that of her photographer boyfriend, Robert [sic]. Rose is downstairs). Looking vaguely Spanish, she exhibits her overflowing beauty a little uncomfortably. It took little for the two young girls from Glasgow to descend on London, following in the footsteps of ‘friends’ Orange Juice. First a publishing deal with Zoo, then a single for Will Sargeant’s label. titled ‘Trees and Flowers’ and recorded with the help of some Madness, Fun Boy Three and the superlative Roddy Frame, and finally the unusual Liverpool Connection, encouraged by ex-Teardrop Explodes David Balfe, produced some appreciable results: a contract with Korova/WEA, a couple of fortunate singles (‘Since Yesterday’ and ‘Let Her Go’) and a debut album, ‘Strawberry Switchblade’, as sweet and gratuitous as 90% of the purest Sixties pop.

Sweetly naive, Rose and Jill get a kick out of being pampered by the trade press, fashion magazines and even mainstream women’s magazines. Not bad for a group that was formed (in their own words) ‘just to be noticed’.

‘It’s true,’ begins the talkative Rose, ‘we formed Strawberry Switchblade before we knew how to play any instruments. But ever since ’77 I dreamed of singing in a band one day. It was punk that made me discover that it was not at all necessary to have a musical education, a so-called training, in order to make records. Jill and I just wanted to have fun, to sing together, to play live. For a whole year we performed in real shitholes, then we realised that this was the path we really wanted to follow. Frankly, though, our goal was never to break into the Top Ten’.

Rather surprising that two young girls in their early twenties would go on to reclaim a sound as specific as the American girl-groups of the sixties, or is it? It is Jill who answers, the look eternally downbeat: ‘We really liked singing together, a bit in the style of Mamas and Papas. Perhaps the very fact that we both play acoustic guitars, while occasionally resorting to electronics, gives our music that Sixties-ish tinge, but it’s not intentional’.

Rather surprising that two young girls in their early twenties would go on to reclaim a sound as specific as the American girl-groups of the sixties, or is it? It is Jill who answers, the look eternally downbeat: ‘We really liked singing together, a bit in the style of Mamas and Papas. Perhaps the very fact that we both play acoustic guitars, while occasionally resorting to electronics, gives our music that Sixties-ish tinge, but it’s not intentional’.

‘I think that, after the Sixties, a certain melodic tradition fell into disuse in the pop sphere,’ Rose adds. ‘We had heavy-rock, punk, ethno-funk, but no great melody or even vocal harmonies. That’s what we are interested in recovering, not the spirit of the lost Sixties. Sure, it would have amused me a lot to be a teenager in that particular period: all that inventing one fashion after another, one dance after another. Fortunately, from a categorised point of view, we were able to experience another musical revolution with the advent of punk, which was undoubtedly a more exciting experience because it was live’.

And this mania to disguise yourselves, to camouflage yourselves, doesn’t seem obvious to you now, deja vu, essentially an excuse to disguise a certain poverty of ideas?

Jill’s smile (finally) is proportional to my embarrassment at having added a new shade of beige to her carpet by inadvertently spilling my instant coffee: ‘We never thought we had to have an image at all costs. We already had it seven years ago when we started the group. I would find the opposite attitude more forced, not wanting to dress up at all costs because, as you say, it’s taken for granted. Of course, such a strong image gets us noticed by everyone, but at the end of the day all we are doing is continuing something that we enjoy and that we started many years ago. Does it also sell more records? All the better!’

Rose shakes her mane of ribbons, touches up her blush and lipstick, and then intervenes: ‘We have always lived by our own rules, in life as in dress. For us there is no need to wait until Hallowe’en to dress up, we naturally do it every day. Rather, adopting a similar look saves you from having to update according to current fashions. We are both small in stature and stylists seem to design their collections exclusively for a certain type of woman of which we are the very antithesis! (laughs) The same goes for certain colours that cannot be found in a normal make-up range. That’s why we design our clothes ourselves. Why are we wearing black today? Hahaha! Because this is our casual look! Hahaha! So when you walk down the street, no one comes to bother you! And it’s more practical’.

Aren’t you afraid of being branded as one of the many novelty bands that come and go every six months?

Rose: ‘Frankly, no, although we have been labelled just that. I hope our album proves the opposite, that we can write great pop songs and that the public likes them. Having such a strong image is always a handicap’.

Do you have your own concept of ‘style’?

Jill: ‘What can I tell you? Being comfortable with yourself, instead of being constantly bombarded by negative external stimuli. Too many people allow themselves to be conditioned by what others expect: look at middle-aged people and how they dress. But Tina Turner does not sounds like a middle-aged lady at all! It takes courage, but the message is this: be yourself’.

Rose meanwhile operated the video recorder. The two videos made by Julian Temple [sic] for ‘Since Yesterday’ and ‘Let Her Go’ appear on the monitor. The two young girls are mesmerised for about ten minutes by the flood coloured polka dots superimposed on their black and white images. It takes a few seconds for Rose and Jill’s comedown to be complete.

‘It was great and very easy with Temple,’ comments Jill. ‘We explained our ideas to him: no dancers, no lunging down mysterious corridors, no medieval-futuristic set design.’ They exchange a glance of understanding, the flash of a smile, enough to realise that the typical enthusiasm of the early days is more alive than ever. Inspired amateurism.

Hmm, better to leaf through the dossier of the two. ‘I grew up in the affluent part of Glasgow,’ says Jill, ‘although you can’t say I came from a wealthy family. I went to a so-called ‘comprehensive’ school and then went to art school for four years.

‘I come from the east side of Glasgow,’ Rose responds. ‘My family was particularly large. I also went to comprehensive school, which I later dropped out at the age of sixteen to be a singer. I’ve also had occasional employment, but music has always been the focus of my life. ‘Originally I wanted to be an artist,’ Jill adds, which is why I enrolled in art school. I had always listened to music but, not knowing how to play any instruments, I never thought I would make it. It wasn’t until punk revolutionised the whole music scene by breaking a lot of rules that I felt like trying.

‘It wasn’t until I was in my twenties that I learned to play guitar, aware of a great truth: even underneath the most complex and intricate arrangement, there has to be a very simple song with a great melody. At the end of the day, that’s what makes your records sell. Sure, I regret not being able to continue studying design and art, but being part of a band means working at 360 degrees: designing the wardrobe, designing the cover graphics, etc.’

Who were you inspired by when forming Strawberry Switchblade?

Rose: ‘Everything from the past influences you to varying degrees, even what you hate, but we were never talented enough to copy anything. So we had to come up with something of our own and make the most of it. Anyway, we always loved the Velvet Underground. I always wanted to write songs as good as theirs’.

Jill: ‘I always tried to keep a certain distance from my loves, however I could give you Simon & Garfunkel and the Lovin’ Spoonful. Of course we were very young at the time when these artists were all the rage.

We discovered them on certain evenings spent with Orange Juice listening to old records from the sixties. I would probably never have listened to them at all. My father then had a couple of Kinks records. We also didn’t miss all sorts of references mentioned in interviews of our favourite bands.’ Orange Juice Postcard Records. What was your role within that music scene? ‘We were very much part of the Postcard scene,’ says Jill.

‘We used to all get together a lot, but when those bands had even the slightest success they moved to London. So Strawberry Switchblade was born almost as a way of filling a void, so much so that we started working in the cottage that the Juice bequeathed to us. Then along came David Balfe, ex-Teardrop Explodes, who introduced us to a whole new circle of people. He also introduced us here in London and quickly became our manager’.

What the hell was a female duo from Glasgow doing on a Liverpool label like Zoo? ‘Pretty weird, eh?’ gurgles Jill in laughter. ‘They were Postcard’s direct rivals! They had heard us on the radio and Balfe came and offered us a publishing contract. Money! We got other offers, but we chose them because they were young, enthusiastic, and Balfe was in a band. He was the one who got us the contract with Korova’.

And today you are in the ‘big apple’ in London. How has your opinion of the current UK scene changed?

Jill: ‘It hasn’t changed that much. Wham remains an irrelevant band like a thousand others, like watching ‘Dallas’ on TV: a complete cowardly escape from reality. There is an alternative, sure: people like Billy Bragg, UB40. Psychic TV, Style Council. As long as there is someone like them as a counterbalance, the taste for a certain kind of superior music will remain intact’.

It slips, as seems natural these days with Anglo-Saxon bands, into political discourse, social commitment and benefits à la Band Aid. For Jill it is imperative that ‘general attention should be diverted to the problems we already have here in England. Unemployment, disinformation, etc. The important thing is to keep doing your job knowing that at the same time you are helping others. Anyone can afford to donate the proceeds of a couple of concerts during a tour. There is no need to make a case for it, like Band Aid. And then the important thing is to inform, to publicise what the real causes are to fight for.

‘Younger people do not have the experience to really understand the depth and complexity of certain issues: by reading an interview of their favourite artists, they might learn something more than the usual nonsense. The power of certain megastars should not only serve to foolishly dominate public reactions. That’s why we admire Bronski Beat’.

Rose says bye-bye. She has to run to a recording studio to give a couple of choruses to the new effort of her friend Genesis P. Orridge. The last question stops her at the door, still continually smiling.

And if you were to return to the darkness of anonymity, would such a prospect frighten you?

Jill recomposes herself for a moment, adjusting her gaucho hat, and finally sighs: ‘No. We would still be able to do what we enjoy and be satisfied. After all, we were happy in our anonymity anyway! (laughs)’.

‘You don’t need so much popularity to write good songs and enjoy the fruits of your labour,’ Rose adds. ‘Happiness matters far more than any success. Too many people desperately want to be famous, they don’t give a damn about music, about art. And then what? Once they become famous, they start worrying about how famous they are, how famous they will stay. It’s absurd, isn’t it?’

We walk down the stairs together, cats scampering off everywhere. Hmm, spring has sprung even here in Muswell Hill. Black has never put me in such a good mood as tonight.

Di Guido Harari

Senza i pois, la Strawberry Switchblade non sarebbero mai venute alla ribalia. La qualiano non acesse inventato qual ruriasa disegno, non sarebbe slata passibile ammirare queste dui luoilulle chi si divertona a nasconderal dietra due indecorosi abitlal e a larel credere di essere laganue, dirincantate e stupite dal clamare che improvvisanente le ha circondate. Un preciso disegno e la riscoperta dello stesso tipo di pop che sprio dei nobili predecessori come Gerry Goffin e Carole King co le consegnano invece per cio che sono: brave, astute e un po’ furfasti.

Quel tanghero del tassista non se ne sta zitto un secondo, «Hey, Muswell Hill? Ouest’indirizzo non mi e nuovo. Si tratta di un gruppo? Hey, non sono forse quelle due ragazzine bislacche, come cavolo si chiamano?», e via a raccontare di quando i Frankies gli hanno vomitato in macchina («erano ancora agli inizi e abitavano in quell’alberghetto laggiù») e di quanto sono carucci i Bronski Beat («Larry abita ad un paio di isolati da casa mia»).

Non sa frenarsi neppure una volta staccato il tassametro davanti ad un anonimo block color diarrea («dev’essere l’appartamento 2, o il 9, non so. Ci ho portato una troupe televisiva l’altra settimana blablabla») e ci vuole una mancia consistente per toglierselo dai piedi.

Di un ascensore neppure l’ombra, che piano sarà? S’apre una porta all’improvviso ed ecco spuntare Rose MacDowell, un peperino tutto nero con due occhi da gatta ed un impenetrabile accento scozzese. L’appartamento è, per usare un eufemismo, un buco. Soffitti rosa, pareti «affrescate» con autoritratti a pois (un motivo ricorrente nel guardaroba delle Strawberry Switchblade), una giusta dose di suppellettili junk, la TV accesa, videoregistratore di marca, niente libri. Sul gran tappeto del salotto sta distesa Jill Bryson (l’appartamento è suo e del suo boyfriend fotografo, Robert. Rose sta al piano di sotto).

Look vagamente spagnoleggiante, esibisce un po a disagio la sua bellezza debordante. C’è voluto poco perché le due ragazzine di Glasgow calassero a Londra, sulle orme degli «amici» Orange Juice. Prima un contratto editoriale con la Zoo, poi un singolo per l’etichetta di Will Sargeant. intitolato «Trees and Flowers» e registrato con l’aiu-to di alcuni Madness, Fun Boy Three e dell’irriducibile Roddy Frame, e finalmente l’insolita Liverpool Connection, incoraggiata dall’ex-Teardrop Explodes David Balfe, ha prodotto dei risultati apprezzabili: un contratto con la Korova/WEA, un paio di singoli fortunati («Since Yesterday» e «Let Her Go») ed un album d’esordio, «Strawberry Switchblade», zuccherosamente inutile come il 90% del più puro pop anni Sessanta.

Dolcemente naif, queste Rose e Jill se la godono un mondo a vedersi coccolate dalla stampa specializzata, dalle riviste di moda e persino dalle magazines femminili più tradizionali. Niente male per un gruppo che si é formato (parole loro) «solo per essere notato». «È vero», esordisce la loquace Rose, «abbiamo formato le Strawberry Switchblade prim’ancora di saper suonare un qualunque strumento. Ma fin dal ’77 ho sognato di cantare un giorno in un gruppo. Fu il punk a farmi scoprire che non era affatto necessario avere un’educazione musicale, un cosiddetto training, per poter incidere dei dischi. Jill ed io volevamo soltanto divertirci, cantare insieme, suonare dal vivo. Per un anno intero ci siamo esibite in vere e proprie topaie, poi abbiamo capito che questa era la strada che volevamo seguire davvero. Francamente, però, il nostro obiettivo non e mai stato quello di sfondare nei Top Ten».

Piuttosto sorprendente che due ragazzine poco più che ventenni vadano a recuperare un sound cosi specifico com’è quello dei girl-groups americani degli anni Sessanta, o no? È Jill a rispondere, lo sguar do eternamente abbassato: «Ci piaceva molto cantare in coro, un po’ nello stile dei Mama’s & Papa’s. Forse il fatto stesso che entrambe suoniamo chitarre acustiche, pur ricorrendo talvolta all’elettronica, conferisce alla nostra musica quella sfumatura cosi anni Sessanta, ma non é voluto».

«Credo che, dopo gli anni Sessanta, una certa tradizione melodica sia caduta in disuso nell’ambito pop», aggiunge Rose. «Abbiamo avuto l’heavy-rock, il punk, l’etno-funk, ma nessuna grande melodia e neppure armonie vocali. Questo è quel che ci interessa recuperare, non lo spirito dei perduti anni Sessanta. Sicuro, mi avrebbe molto divertito essere una teenager in quel particolare periodo: tutto quell’inventarsi una moda dopo l’altra, un ballo dopo l’altro. Fortunatamente, dal punto di vista anagrafico, siamo state in grado di vivere un’altra rivoluzione musicale con l’avvento del punk, un’esperienza senz’altro più eccitante perché vissuta in presa diretta».

E questa mania di travestirvi, di camuffarvi, non vi pare ormai scontata, dela vu, tutto sommato un alibi per mascherare una certa qual povertà d’idee? Il sorriso (finalmente) di Jill é proporzionale al mio imbarazzo per aver aggiunto una nuova sfumatura di beige al suo tappeto versandovi inavvertitamente il mio instant coffee: «Non abbiamo mai pensato di dover avere un’immagine a tutti i costi. L’avevamo gia sette anni fa, quando demmo vita al gruppo. Troverei più forzato l’atteggiamento opposto, il non volersi travestire a tutti i costi perché, come dici tu, è scontato. Certo, un’immagine cosi forte ci fa notare da tutti, ma in fondo non facciamo altro che continuare qualcosa che ci diverte e che abbiamo cominciato tanti anni fa. Ci fa vendere anche più dischi? Tanto meglio!».

Rose scuote la criniera infarcita di nastri e nastrini, si ritocca fard e rossetto, per poi intervenire: «Abbiamo sempre vissuto seguendo le nosto regole, nella vita come nell’abbigliamento. Per noi non c’é bisogno d’aspettare Halloween per travestirci, lo facciamo naturalmente lutti i giorni. Piuttosto, l’adozione di un look simile ti evita di doverti aggiornare in base alle mode correnti. Siamo entrambe piccole di statura e gli stilisti sembrano progettare le loro collezioni esclusivamente per un certo tipo di donna di cui noi siamo proprio l’antitesi! (ride) Lo stesso vale per certi colori introvabili in una normale gamma di trucchi. Per questo disegnamo noi stesse i nostri abiti. Perché vestiamo di nero oggi? Hahahaha! Perché questo è il nostro look casual! Hahaha! Cosi quando te ne vai in giro per la strada, nessuno viene a darti fastidio! E più pratico».

Non temete di venir bollate come una delle tante novelty bands che vanno e vengono ogni sei mesi? Rose: «Francamente no, malgrado ci abbiano etichettato proprio cosi. Spero che il nostro album provi il contrario, che sappiamo scrivere ottime pop songs e che il pubblico le gradisce. Avere un’immagine cosi forte è sempre un handicap».

Avete un vostro concetto di «stile»? Jill: «Cosa posso dirti? Essere a proprio agio con se stessi, invece d’essere costantemente bombardati da stimoli esterni negativi. Troppa gente si lascia condizionare da ciò che gli altri s’aspettano: guarda la gente di mezza età e come si veste. Ma Tina Turner non mi sembra affatto una signora di mezza età! Ci vuol coraggio. ma il messaggio è questo: siate voi stessi».

Rose intanto ha azionato il videoregistratore. Appaiono sul monitor i due video realizzati dal solito Julian Temple per «Since Yesterday» e «Let Her Go». Le due ragazzine rimangono ipnotizzate per una decina di minuti davanti al diluvio di pois colorati che vanno a sovrapporsi alle loro immagini in bianco e nero. Ci vogliono alcuni secondi perché il comedown di Rose e Jill sia completo. «È stato fantastico e semplicissimo con Temple», commenta Jill. «Gli abbiamo spiegato le nostre idee: niente ballerini, nessuna corsa affannata lungo misteriosi corridoi, nessuna scenografia medievalfuturistica».

Si scambiano un’occhiata d’intesa, il lampo d’un sorriso, quanto basta per capire che il tipico entusiasmo degli esordi é più che mai vivo. Dilettantismo ispirato. mmm, meglio sfogliare con maggior cura il dossier delle due. «Sono cresciuta nella parte benestante di Glasgow», racconta Jill, «malgrado non si possa dire che provengo da una famiglia agiata. Ho frequentato una scuola cosiddetta ‘comprensiva’ per poi passare all’art-school per quattr’anni».

«Io invece vengo dall’ east side di Glasgow», ribatte Rose, «La mia famiglia era particolarmente numerosa. Anch’io ho frequentato una comprehensive school che ho poi mollato all’età di sedici anni per fare la cantante. Ho anche avuto un impiego occasionale, ma la musica è sempre stata il fulcro della mia vita». «In origine volevo essere un’artista», aggiunge Jill, ed è per questo che mi sono iscritta art-school. Ho sempre ascoltato musica ma, non sapendo suonare nessuno strumento, non avrei mai pensato di farcela. Solo quando il punk rivoluzionò l’intero panorama musicale sowenendo parecchie regole, mi venne voglia di provarci. Fu solo a vent’anni che imparai a suonare la chitarra, conscia di una grande verita: anche sotto l’arrangiamento pii complesso e arzigogolato. deve esserci una canzone semplicissima con una grande melodia. Alla fin della fiera questo é quello che fard vendere i tuoi dischi. Sicuro, mi dispiace di non poter continuare a studiare design e arte, però far parte di un gruppo significa lavorare a 360 gradi: disegnare il guardaroba, concepire la grafica delle copertine, etc.»

A chi vi siete ispirate formando Strawberry Switchblade?

Rose: «Tutto del passato ti influenza in varia misura, persino quel che detesti, ma noi non abbiamo mai avuto il talento sufficiente per copiare una qualunque cosa. Perciò abbiamo dovuto elaborare qualcosa di nostro e trarne il massimo profitto. Ad ogni modo abbiamo sempre amato i Velvet Underground. Ho sempre desiderato scrivere canzoni valide quanto le loro».

Jill: «Ho sempre cercato di mantenere una certa distanza dai miei amori, comunque potrei darti Simon & Garfunkel e i Lovin’ Spoonful. Ovviamente eravamo giovanissime all’epoca in cui questi artisti fecero furore.

Li abbiamo scoperti in certe serate trascorse con gli Orange Juice ad ascoltare vecchi dischi degli anni Sessanta. Probabilmente. non mi sarebbe mai capitato di ascoltarli alUimenti. Mio padre poi aveva un paio di dischi dei Kinks. Non ci siamo neppure lasciate sfuggire ogni sorta di riferimento citato nelle interviste dei nostri gruppi preferitti.»

Orange Juice Postcard Records. Quale era il vostro ruolo all’interno di quella scena musicale? «Eravamo molto inserite nel giro Postcard,» racconta Jill. «Ci trovavamo spesso tutti insieme, ma quando quei gruppi riscossero il pur minimo successo si trasferirono tuffi a Londra. Perciò le Strawberry Switchblade nacquero quasi per colmare un vuoto, tant’è che cominciammo a lavorare nel cottage che i Juice ci lasciarono in eredita. Poi arrivò David Balfe, exTeardrop Explodes, che a presentò un giro di persone completamente nuovo. inserendoci anche qui a Londra e diventando in breve il nostro manager».

Che diavolo ci faceva un duo femminile di Glasgow su un’etichetta di Liverpool come la Zoo? «Davvero strano, eh?» gorgoglia Jill tra le risate. «Erano i rivali diretti della Postcard! Ci avevano ascoltate alla radio e Balfe venne ad offrirci un contratto editoriale. Soldi! Ricevemmo altre offerte, ma scegliemmo loro perché erano giovani, entusiasti, e Balfe aveva fano parte di un gruppo. Fu lui a procurarci il contratto con la Korova».

E oggi che vi trovate nella «grande mela» londmese, com’è mutata la vostra opinione sull’attuale scena inglese?

Jill: «Non è mutata più di tanto. I Wham rimangono un gruppo irrilevante come mille altri, come guardare ‘Dallas’ alla TV: una fuga completa e vigliacca dalla realtà. Esiste un’alternativa, sicuro: gente come Billy Bragg, UB40. Psychic TV, gli Style Council. Finché ci sarà qualcuno come loro a far da contraltare, rimarrà intatto il gusto per un certo tipo di musica superiore».

Si scivola, come pare ormai naturale di questi tempi con i gruppi anglosassoni, sul discorso politico, sull’impegno sociale e sui benefit à la Band Aid. Per Jill è imprescindibile che «l’attenzione generale andrebbe deviata sui problemi che abbiamo già qui, in Inghilterra. La disoccupazione, la disinforrnazione, etc. L’importante é continuare a fare d proprio lavoro sapendo che allo stesso tempo stai aiutando il prossimo. Chiunque può permettersi di devolvere gli incassi di un paio di concerti nell’arco di una tournée. Non c’è bisogno di farne un caso, come Band Aid. E poi l’importante é informare, divulgare quali sono le vere cause per cui si deve battersi.

I più giovani non hanno l’esperienza sufficiente per comprendere realmente la profondità e la complessità di certi problemi: leggendo un intervista dei loro artisti preferiti, potrebbero apprendere qualcosa di più delle solite fandonie. Il potere di certe megastars non deve servire soltanto a dominare stupidamente le reazioni del pubblico. Per questo ammiriamo i Bronski Beat».

Rose dice byebye. Deve correre in uno studio di registrazione per regalare un paio di coretti alla nuova fatica del suo amico Genesis P. Orridge. L’ultima domanda la inchioda sulla porta, eternamente sorridente.

E se doveste tornare nell’oscurità dell’anonimalo, vi farebbe paura una simile prospettiva? Jill si ricompone per un attimo, aggiustandosi il cappello da gaucho, e infine sospira: «No. riusciremmo lo stesso a fare ciò che più ci piace e soddisfa. In fondo, eravamo comunque felici nel nostro anonimato! (ride)».

«Non hai bisogno di tanta popolarità per scrivere buone canzoni e goderti i frutti del tuo lavoro», aggiunge Rose. «La felicità conta assai più di qualunque successo. Troppa gente vuole disperatamente essere famosa, se ne frega della musica, dell’arte. E poi? Una volta diventati famosi, cominciano a preoccuparsi di quanto sono famosi, di quanto rimarranno famosi. E assurdo, non trovi?».

Scendiamo le scale insieme, coi gatti che schizzano via da ogni parte. Mmm, la primavera é amvata anche qui a Muswell Hill. Il nero non mi aveva mai messo cosi di buonumore come stasera.